Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Cluster System and Energy

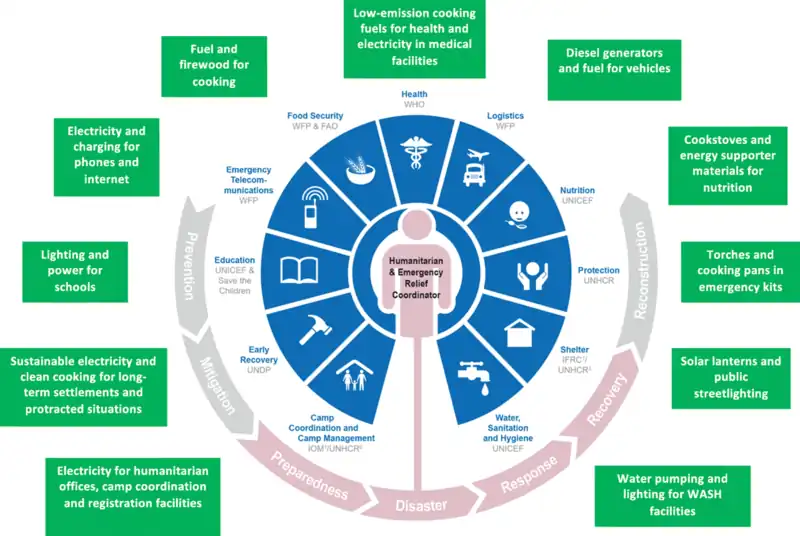

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Humanitarian Cluster System was introduced in 2005 to strengthen coordination across UN and non-UN partners engaged in non-refugee humanitarian emergencies.[1] It includes 11 global clusters, each led by designated UN agencies in collaboration with NGOs and national authorities.[2] In emergencies that include refugees, UNHCR applies the Refugee Coordination Model (RCM), which calls for the establishment of inter-sectoral working groups that closely mirror the cluster system.[3]

Energy is not a standalone need in the humanitarian response; rather, it is a cross-cutting enabler essential to the effective functioning of all clusters within the system.[4] However, the lack of a designated cluster for energy has meant that its coordination within the response is often fragmented and deprioritized. This leads to siloed procurement and implementation of energy solutions, hinders the uptake of solar and other renewable and low-carbon energy technologies by humanitarian actors, and limits the ability of these actors to provide reliable energy access to communities in protracted situations of fragility and displacement.

In contrast, improved coordination of energy in the humanitarian response has a number of benefits for organizations, including cost savings and enhanced security of operational energy supply for all cluster partners. Greater coordination is also essential for accelerating the humanitarian sector’s progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and particularly SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy for All and SDG 13: Climate Action.

Evolving Coordination Efforts

Efforts to strengthen energy coordination in the Cluster System began with the establishment of the Safe Access to Fuel and Energy (SAFE) in Humanitarian Settings Working Group in 2007 to improve coordination, knowledge sharing, and research on fuel and energy needs for conflict-affected populations.[5] The Moving Energy Initiative (MEI), which ran from 2014 to 2018, was established to produce research and raise awareness about the importance of humanitarian energy policy and practice.[6]

In 2018, the Global Platform for Action (GPA) on Sustainable Development in Displacement Settings was established as the inter-agency platform to ensure energy access for displaced and host communities affected by conflict and crisis.[7] The GPA Secretariat and its partners foster collaboration among humanitarian, development, government, and private sector actors to scale energy access solutions for clean cooking and electricity. They also work to transition humanitarian responses toward more sustainable energy solutions.

At the field level, coordination of energy in humanitarian emergency and displacement settings today often occurs through Energy and Environment Technical Working Groups (EETWGs), which have been introduced in countries such as Uganda, Ethiopia, and Venezuela. These groups support training, knowledge sharing, and joint planning among clusters activated in the humanitarian response. The Humanitarian Energy Exchange Network (HEEN) also serves as a coordination space for experienced energy and humanitarian practitioners operating globally to exchange knowledge and coordinate activities.

Individual humanitarian energy projects have also been implemented in several countries. Examples include the Humanitarian Engineering and Energy for Displacement (HEED) project in Rwanda and Nepal, the Alianza Shire projects in Ethiopia, Renewable Energy for Refugees (RE4R) in Rwanda and Jordan, and the Energy Solutions for Displacement Settings (ESDS) project in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda.

Energy as an Enabler for Each Cluster

While energy is not a standalone cluster in the IASC Cluster System, it is essential for achieving the objectives of all clusters. Clean, reliable and affordable energy access enhances service delivery, reduces risks, and supports sustainability across humanitarian operations. Below is an overview of how energy enables each cluster’s work.

Protection Cluster

Cluster Leads: IOM and UNHCR

Energy intersects with the Protection Cluster in numerous ways, with firewood collection for cooking, lighting, and heating as a key focus. Firewood is often the energy source of first resort in displacement settings, but the need to travel outside of a settlement to collect it can expose individuals, and particularly the women and girls commonly tasked with this work, to dangers such as armed robbery, sexual violence, and wild animals. Resource depletion caused by displaced people seeking firewood can also drive environmental degradation and spark tensions with host communities. Having access to alternative energy and electricity sources to meet basic needs as well as more fuel-efficient clean cookstoves can reduce these protection risks. Additionally, lighting for public spaces and services, households, and individuals can increase safety within a settlement.

Food Security Cluster

Cluster Leads: WFP and FAO

Energy access is a crucial enabler of the work of the Food Security Cluster, as it allows displaced people to safely cook and store food. Yet coordination around access to fuel and cooking technologies is often challenging and underfunded. In situations where displaced people are not equipped with sufficient appliances and fuel to cook food, and firewood availability is inadequate, they may exchange food rations or other items for fuel, undercook their food, or start fires by burning plastics and other toxic waste. Thus, inadequate energy for meal preparation puts food security at risk and may lead to malnutrition. Additionally, energy is essential for mechanizing agricultural production and processing activities, which contributes to food security through higher crop yields, extended safe food storage, and improved linkages to markets.

Health Cluster

Cluster Lead: WHO

WHO leads the Health Cluster, and access to reliable electricity for health facilities is essential to enhancing the quality of care provided in humanitarian emergencies. Electricity provides lighting and cooling for patient and staff comfort, powers medical equipment, and keeps perishable drugs and vaccinations cool. Clean cooking technology also plays an important role in improving the health of people impacted by humanitarian emergencies. Household air pollution caused by burning firewood, charcoal, and kerosene contributes to increased risk of diseases such as respiratory illnesses, childhood pneumonia, heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer, among others.[9] Using open fires for cooking also increases the possibility of burns or incidents of fire in refugee settlements.

Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)

Cluster Lead: UNICEF

As with the health and education clusters, energy is crucial to the effective delivery of services by the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Cluster, and particularly clean and potable water supply. In humanitarian contexts, water pumping and purification activities are typically powered by diesel generators, although efforts are being made in many contexts to transition to solar and hybrid solutions. Biogas produced from sanitation waste is also a potential source of energy as well as a waste management solution, though implementing such projects has proven financially and logistically difficult.

Nutrition Cluster

Cluster Lead: UNICEF

Working closely with the Food Security, Health, and WASH clusters, the Nutrition Cluster aims to minimize malnutrition, insecurity, and public health risks regarding food in humanitarian settings. As discussed above, providing reliable access to clean cooking fuels and cold chain solutions, as well as enhancing local agricultural production through mechanization with clean electricity, are all important for improving the nutrition of displaced people.

Shelter Cluster

Cluster Leads: IFRC and UNHCR

Integration of electricity and clean energy supply into shelter construction in both temporary and protracted humanitarian settlements can improve the quality and safety of housing, schools, and other spaces for displaced people. In countries which experience weather extremes, providing heating during cold weather or cooling fans during summer can be essential. Cooking equipment is also related to the Shelter Cluster’s work. Humanitarian settlements are typically densely packed, and use of firewood and other traditional fuels that require an open flame increases fire risk and health hazards. Cookstoves also often double as heaters in households where another option is not available and insulation is insufficient.

The Shelter Cluster is well positioned to integrate energy efficiency measures into the humanitarian response, including the development of better-insulated buildings, which reduces the need for cooling and heating. An emergency’s impact on local firewood supply, and related tensions with host communities, can be mitigated through the use of other materials in shelter construction.

Education Cluster

Cluster Leads: Save the Children and UNICEF

Electricity in both schools and households improves the quality of education services provided to people living in displacement, which is coordinate by the Education Cluster. Adequate lighting provides a more comfortable learning environment and can support the retention of staff and students. Nighttime lighting allows facilities to be open longer and opens up more study hours. Electricity supply is also essential for accessing the Internet to support both student learning and teacher training. Access to clean cooking, meanwhile, allows for the preparation of healthy meals for children, supporting the delivery of adequate nutrition. Enabling meal provision at schools with institutional clean cooking solutions can also reduce the hours spent collecting household firewood, possibly increasing children’s attendance at school. Finally, awareness-raising around sustainable energy, clean cooking, energy efficiency, and other relevant topics can be coordinated through the Education Cluster.

Logistics

Cluster Lead: WFP

The Logistics Cluster has significant impact on energy supply reliability, fuel choices, and energy-related environmental impacts of humanitarian operations. It facilitates the delivery of energy sources for operations, including camps and vehicles. Today, humanitarian operations are primarily reliant on diesel generators and require support from the Logistics Cluster to procure fuel. The cluster facilitated the delivery of 1.5 million litres of fuel in 2018.[10] In the context of the transition to sustainable energy, the Logistics Cluster is responsible for leading efforts to green the humanitarian supply chain.[11] This effort includes developing resources to support decarbonization of humanitarian energy supply as well as circular economy and management approaches to minimize creation of and safely dispose of e-waste.[12]

Emergency Telecommunications Cluster

Cluster Lead: WFP

Connectivity services require reliable energy supply, and as such, the Emergency Telecommunications Cluster is often responsible for deploying power and back-up power sources for ICT equipment. Mobile phones are important for both humanitarian responders and crisis-affected people, as they support communication, information access, and financial services access, including for the pay-as-you-go and “cash”-based aid distribution services often available in displacement contexts. Mobile phones, however, need to be charged, making reliable access to power for charging an important part of the connectivity component of the humanitarian response.

Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster

Cluster Leads: IOM and UNHCR

Safe and accessible energy impacts several areas of responsibility for the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster. As previously discussed, depletion of firewood and other natural resources can drive tensions between displaced and host communities. Open fires for cooking, heating, and lighting in crowded camps also pose significant health and safety risks. The CCCM Cluster plays a crucial role in ensuring that sustainable energy sources, especially for households, are available and safely accessible for camp residents, and for host communities where applicable. As this cluster works closely with displaced and host communities, it can also help identify local dynamics, needs, concerns, and preferences that will shape the design of humanitarian energy projects.

Early Recovery Cluster

Cluster Lead: UNDP

Access to reliable, affordable energy sources that can continue to operate sustainably over the long term is an essential foundation to the work led by the Early Recovery Cluster. Energy is necessary for restoring public services and infrastructure as well as generating livelihood opportunities. Access to reliable electricity creates opportunities to establish new micro and small-enterprises in agriculture, food processing, welding, tailoring, and other areas. Installation of renewable energy sources, such as rooftop solar systems and mini-grids, can also create opportunities for community members to be trained in the construction, operation, and maintenance of these systems. The Early Recovery Cluster is also positioned to support the mainstreaming of green reconstruction efforts, such as energy-efficient buildings an solar-powered public lighting.

References

- ↑ United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). “We Coordinate.” UNOCHA. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://www.unocha.org/we-coordinate.

- ↑ UNHCR. “Cluster Approach.” UNHCR Emergency Handbook. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://emergency.unhcr.org/coordination-and-communication/cluster-system/cluster-approach.

- ↑ UNHCR. “Refugee Coordination Model (RCM).” UNHCR Emergency Handbook. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://emergency.unhcr.org/coordination-and-communication/refugee-coordination-model/refugee-coordination-model-rcm.

- ↑ Thomas, Patrick J.M., Sarah Rosenberg-Jansen, and Abigail Jenks. “Moving Beyond Informal Action: Sustainable Energy and the Humanitarian Response System.” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 6, no. 1 (2021): 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-021-00102-x.

- ↑ Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). Safe Access to Fuel and Energy (SAFE) Task Force: Terms of Reference. February 2016. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/sites/default/files/migrated/2016-02/safe_working_group_tor_2016.pdf.

- ↑ Chatham House. “Moving Energy Initiative: Sustainable Energy for Displacement Settings.” Chatham House. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://www.chathamhouse.org/about-us/our-departments/environment-and-society-centre/moving-energy-initiative-sustainable-energy.

- ↑ Global Platform for Action on Sustainable Energy in Displacement Settings (GPA). Strategic Framework for Action: Delivering Sustainable Energy in Humanitarian Settings. 2018. https://www.humanitarianenergy.org/assets/uploads/gpa_framework_final-compressed.pdf.

- ↑ Thomas, Patrick J.M., Sarah Rosenberg-Jansen, and Abigail Jenks. “Moving Beyond Informal Action: Sustainable Energy and the Humanitarian Response System.” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 6, no. 1 (2021): 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-021-00102-x

- ↑ Clean Cooking Alliance. “Health.” Clean Cooking Alliance. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://cleancooking.org/the-issues/health/#:~:text=Exposure%20to%20HAP%20from%20burning,%2C%20stroke%2C%20and%20lung%20cancer.

- ↑ Logistics Cluster. Annual Report 2018. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://logcluster.org/annualreport/2018/.

- ↑ Logistics Cluster. “Green Logistics.” WREC Coalition. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://logcluster.org/en/wrec/green-logistics.

- ↑ Logistics Cluster. “WREC Coalition.” LogIE: Logistics Information Exchange Platform. Accessed May 1, 2025. https://logie.logcluster.org/?op=wrec.