1923 Spanish general election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

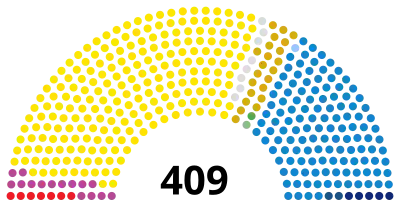

All 409 seats in the Congress of Deputies and 180 (of 360) seats in the Senate 205 seats needed for a majority in the Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 4,782,347 (total) 3,128,928 (non-Article 29) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 2,056,974 (65.7%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A general election was held in Spain on Sunday, 29 April (for the Congress of Deputies) and on Sunday, 13 May 1923 (for the Senate), to elect the members of the 20th Restoration Cortes. All 409 seats in the Congress of Deputies were up for election, as well as 180 of 360 seats in the Senate. This election was the last under the Restoration system, as it would collapse shortly thereafter and give way to the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera.

Amid rising social unrest between trade unions—particularly the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labour (CNT) and the Carlist, yellow Free Trade Unions (Sindicatos Libres)—and the Spanish government, the pistolerismo period saw the assassination of Prime Minister Eduardo Dato in March 1921, as well as the widespread use by Spanish authorities of the ley de fugas method of extrajudicial execution, particularly in Barcelona. During this period of turmoil, a number of Conservative-led governments under Manuel Allendesalazar, Antonio Maura and José Sánchez-Guerra succeeded themselves, each lasting for less than a year.

The election was held against the backdrop of the Picasso file and the parliamentary inquiry committee into the political and legal responsibilities resulting from the disaster of Annual in 1921, in which over 10,000 Spanish soldiers were killed. The debate on responsibilities deepened the divisions within the ruling Conservatives and hastened the downfall of Sánchez-Guerra's government. In a return to the turno system, King Alfonso XIII appointed the Marquis of Alhucemas at the helm of a cabinet formed by the various Liberal factions and the Reformists. A general election was subsequently called, with the Liberal Union securing an overall majority, the first since 1916. Upon its re-opening the parliament resumed its inquiry on the Picasso report.

On 13–15 September 2023, Captain General of Catalonia Miguel Primo de Rivera would take advantage of the political crisis and stage a military coup d'état, blaming the parliamentary system for most of the country’s problems. With the decisive acquiescence of Alfonso XIII—increasingly displeased with parliamentarism and wary of the Picasso report pointing to his own responsibility in the Rif War failures—the coup would lead to Primo de Rivera replacing Alhucemas as prime minister, the establishment of a military directorate at the helm of the country, the declaration of martial law and the dissolution of the Cortes, with the 1876 Constitution being effectively abolished. Primo de Rivera would rule Spain as dictator until his fall in 1930 and the subsequent proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic in 1931.

Background

The Spanish Constitution of 1876 enshrined Spain as a semi-constitutional monarchy, awarding the monarch the right of legislative initiative together with the bicameral Cortes; the capacity to veto laws passed by the legislative body; the power to appoint senators and government members (including the prime minister); as well as the title of commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[1] The monarch would play a key role in the turno system by appointing and dismissing governments, which would then organize elections to provide themselves with a parliamentary majority. This informal system allowed the two major "dynastic" political parties at the time, the Conservatives and the Liberals—characterized as oligarchic, elite parties with loose structures dominated by internal factions, each led by powerful individuals—to alternate in power by means of electoral fraud. This was achieved by assigning candidates to districts before the elections were held (encasillado), then arrange their victory through the links between the Ministry of Governance and the territorial clientelistic networks of provincial governors and local bosses (the caciques), excluding minor parties from the power sharing.[2][3]

The previous election had resulted in the third hung parliament in a row, but with a clear advantage of the Conservatives under Prime Minister Eduardo Dato, who were able to retain power. Following the assassination of Dato in March 1921, the political crisis within his party and the Restoration regime deepened, with an increase in pistolerismo attacks from the Carlist, yellow Free Trade Unions (Spanish: Sindicatos Libres) against members of the anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labour (CNT)—mainly in industrial areas and particulary in Barcelona—and in the crackdown by authorities, seeing an extensive use of the ley de fugas (Spanish for "law of escapes", a type of extrajudicial execution system) by the then-civil governor of Barcelona, Severiano Martínez Anido. A new government was formed under Manuel Allendesalazar, which was immediately forced to manage the political fallout stemming from an anti-political and anti-parliamentarian Córdoba speech by King Alfonso XIII, who criticized the legislative paralysis stemming from political infighting.[4][5][6][7]

The disaster of Annual and the massacre in Mount Arruit in the summer of 1921, a major military defeat in the Rif War in which over 10,000 Spanish soldiers were killed in action, shocked the public opinion and sparked a national crisis that saw the downfall of the Allendesalazar government, its replacement by a national unity government under Antonio Maura (made of conservatives, liberals and the involvement of the Regionalist League of Catalonia) and the start of an investigation into the responsabilities for the defeat (which would come to be known as the "Picasso file").[8] Maura's cabinet was able to stabilize the country's economy, downplay the Defence Juntas by transforming them into "informative commissions" under the authority of the War ministry—to be later entirely disestablished—and launch a renewed military action in Morocco that saw the reoccupation of the territories lost in 1921.[9] The question of the Annual responsibilities, coupled with the withdrawal of parliamentary support from Conservatives and Liberals, led to the end of Maura's government in March 1922 and its replacement by an exclusively Conservative government led by José Sánchez-Guerra.[10][11]

The Picasso report was delivered to the Supreme Council of War and Navy in April 1922—detailing numerous military mistakes, political corruption in Allendesalazar's government, indications of policial and criminal responsibilities and hinting at the blame of the King himself for (allegedly) instigating the ill-prepared advance that brought about the disaster—prompting the creation in July of a parliamentary inquiry committee (the "Commission of Responsibilities") that sparked heated parliamentary debates, particularly from the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE). Mounting pressure on the government, which still included a number of ministers who had been in office during the battle of Annual, prompted Sánchez-Guerra to submit his resignation to the King, who, under the turno system, reluctantly appointed Liberal leader Manuel García Prieto, Marquis of Alhucemas, as new prime minister. Alhucemas' government, intent on implementing an ambitious plan of reforms aimed at democratizing the oligarchic Restoration system—including an expansion of freedom of religion, limits to the government's power to suspend constitutional rights, democratization of the Senate, agrarian law, reaffirmation of civil power, and a progressive tax reform, among others—called a general election for the spring of 1923 in order to provide itself with a parliamentary majority.

Overview

Electoral system

The Spanish Cortes were envisaged as "co-legislative bodies", based on a nearly perfect bicameral system.[12] Both the Congress of Deputies and the Senate had legislative, control and budgetary functions, sharing equal powers except for laws on contributions or public credit, the first reading of which corresponded to Congress, and impeachment processes against government ministers, in which each chamber had separate powers of indictment (Congress) and trial (Senate).[13][14] Voting for each chamber of the Cortes was on the basis of universal manhood suffrage and censitary suffrage, respectively:

- For the Congress, it comprised all national males over 25 years of age, having at least a two-year residency in a municipality and in full enjoyment of their civil rights. Voting was compulsory, though those older than 70, the clergy, first instance judges and public notaries (the latter two categories, within their respective area of jurisdiction) were exempt from this obligation.[15][16][17]

- Electors were required to not being in active military service; nor being sentenced—by a final court ruling—to perpetual disqualification from political rights or public offices, to afflictive penalties not legally rehabilitated at least two years in advance, nor to other criminal penalties that remained unserved at the time of the election; neither being legally incapacitated, bankrupt, insolvent, debtors of public funds, nor homeless.[15]

- For the Senate, it comprised archbishops and bishops (in the ecclesiastical councils); full academics (in the royal academies); rectors, full professors, enrolled doctors, directors of secondary education institutes and heads of special schools in their respective territories (in the universities); members with at least a three-year-old membership (in the economic societies of Friends of the Country); major taxpayers and Spanish citizens of age, being householders residing in Spain and in full enjoyment of their political and civil rights (for delegates in the local councils); and provincial deputies.[18]

The Congress of Deputies was entitled to one member per each 50,000 inhabitants, distributed among the provinces of Spain.[19] 98 seats were distributed among 28 multi-member constituencies and elected using a partial block voting system: in constituencies electing ten seats or more, electors could vote for no more than four candidates less than the number of seats to be allocated; in those with more than eight seats and up to ten, for no more than three less; in those with more than four seats and up to eight, for no more than two less; and in those with more than one seat and up to four, for no more than one less.[20] The remaining seats—311 for the 1923 election—were allocated to single-member districts and elected using plurality voting.[21] Additionally, in those districts where the number of candidates was equal or less than the number of seats up for election, candidates were to be automatically elected.[22]

As a result of the aforementioned allocation, each Congress multi-member constituency was entitled the following seats:[21][23]

| Seats | Constituencies |

|---|---|

| 8 | Madrid |

| 7 | Barcelona |

| 5 | Palma, Seville |

| 4 | Cartagena |

| 3 | Alicante, Almería, Badajoz, Burgos, Cádiz, Córdoba, Gran Canaria, Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Jerez de la Frontera, La Coruña, Lugo, Málaga, Murcia, Oviedo, Pamplona, Santander, Tarragona, Tenerife, Valencia, Valladolid, Zaragoza |

For the Senate, 180 seats were elected using an indirect, write-in, two-round majority voting system.[24][25] Voters in the economic societies, the local councils and major taxpayers elected delegates—equivalent in number to one per each 50 members (in each economic society) or to one-sixth of the councillors (in each local council), with an initial minimum of one—who, together with other voting-able electors, would in turn vote for senators.[26] The provinces of Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia were allocated four seats each, whereas each of the remaining provinces was allocated three seats, for a total of 150.[27][28] The remaining 30 were allocated to special districts comprising a number of institutions, electing one seat each—the archdioceses of Burgos, Granada, Santiago de Compostela, Seville, Tarragona, Toledo, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; the six oldest royal academies (the Royal Spanish; History; Fine Arts of San Fernando; Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences; Moral and Political Sciences and Medicine); the universities of Madrid, Barcelona, Granada, Oviedo, Salamanca, Santiago, Seville, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; and the economic societies of Friends of the Country from Madrid, Barcelona, León, Seville and Valencia.[29]

An additional 180 seats comprised senators in their own right—the monarch's offspring and the heir apparent once coming of age; grandees of Spain with an annual income of at least 60,000 Pt (from their own real estate or from rights that enjoy the same legal consideration); captain generals of the Army and admirals of the Navy; the Patriarch of the Indies and archbishops; and the presidents of the Council of State, the Supreme Court, the Court of Auditors, the Supreme Council of War and Navy, after two years of service—as well as senators for life appointed directly by the monarch.[30]

The law provided for by-elections to fill seats vacated in both the Congress and Senate throughout the legislature's term.[31][32]

Eligibility

For the Congress, Spanish citizens of age, of secular status, in full enjoyment of their civil rights and with the legal capacity to vote could run for election, provided that they were not contractors of public works or services, within the territorial scope of their contracts; nor holders of government-appointed offices, the judiciary, the prosecution ministry and presidents or members of provincial deputations—during their tenure of office and up to one year after their dismissal—in constituencies within the whole or part of their respective area of jurisdiction, except for government ministers and civil servants in the Central Administration.[33][34] A number of other positions were exempt from ineligibility, provided that no more than 40 deputies benefitted from these:[35][36]

- Civil, military and judicial positions with a permanent residence in Madrid and a yearly public salary of at least 12,500 Pt;

- The holders of a number of positions: the president, prosecutors and chamber presidents of the territorial court of Madrid; the rector and full professors of the Central University of Madrid; inspectors of engineers; and general officers of the Army and Navy based in Madrid.

Additionally, candidates intending to run were required to either have previously served as deputies, elected in a general or by-election; to secure the endorsement of two current or former senators or deputies from the same provinces, or from three current or former provincial deputies representing a territory that, in whole or in part, was included in the constituencies for which they sought election; or to secure the endorsement of at least one twentieth of the electorate in the constituencies for which they sought election.[37]

For the Senate, eligibility was limited to Spanish citizens over 35 years of age and not subject to criminal prosecution, disfranchisement nor asset seizure, provided that they were entitled to be appointed as senators in their own right or belonged or had belonged to one of the following categories:[38][39]

- Those who had ever served as senators before the promulgation of the 1876 Constitution; and deputies having served in at least three different congresses or eight terms;

- The holders of a number of positions: presidents of the Senate and the Congress; government ministers; bishops; grandees of Spain not eligible as senators in their own right; and presidents and directors of the royal academies;

- Provided an annual income of at least 7,500 Pt from either their own property, salaries from jobs that cannot be lost except for legally proven cause, or from retirement, withdrawal or termination: full academics of the aforementioned corporations on the first half of the seniority scale in their corps; first-class inspectors general of the corps of civil, mining and forest engineers; and full professors with at least four years of seniority in their category and practice;

- Provided two prior years of service: Army's lieutenant generals and Navy's vice admirals; and other members and prosecutors of the Council of State, the Supreme Court, the Court of Auditors, the Supreme Council of War and Navy, and the dean of the Court of Military Orders;

- Ambassadors after two years of service and plenipotentiaries after four;

- Those with an annual income of 20,000 Pt or were taxpayers with a minimum quota of 4,000 Pt in direct contributions at least two years in advance, provided that they either belonged to the Spanish nobility, had been previously deputies, provincial deputies or mayors in provincial capitals or towns over 20,000 inhabitants.

Other causes of ineligibility for the Senate were imposed on territorial-level officers in government bodies and institutions—during their tenure of office and up to three months after their dismissal—in constituencies within the whole or part of their respective area of jurisdiction; contractors of public works or services; tax collectors and their guarantors; debtors of the State; deputies; local councillors (except those in Madrid); and provincial deputies for their respective provinces.[40]

Election date

The term of each chamber of the Cortes—the Congress and one-half of the elective part of the Senate—expired five years from the date of their previous election, unless they were dissolved earlier.[41] The previous Congress and Senate elections were held on 19 December 1920 and 2 January 1921, which meant that the legislature's terms would have expired on 19 December 1925 and 2 January 1926, respectively. The monarch had the prerogative to dissolve both chambers at any given time—either jointly or separately—and call a snap election.[42][43] There was no constitutional requirement for concurrent elections to the Congress and the Senate, nor for the elective part of the Senate to be renewed in its entirety except in the case that a full dissolution was agreed by the monarch. Still, there was only one case of a separate election (for the Senate in 1877) and no half-Senate elections taking place under the 1876 Constitution.

The Cortes were officially dissolved on 6 April 1923, with the dissolution decree setting the election dates for 29 April (for the Congress) and 13 May 1923 (for the Senate) and scheduling for both chambers to reconvene on 23 May.[44]

Results

Congress of Deputies

| ||||||

| Parties and alliances | Popular vote | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | A.29 | Cont. | Total | ||

| Liberal Union (UL) | 979,435 | 47.62 | 86 | 137 | 223 | |

| Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) | 591,026 | 28.73 | 51 | 73 | 124 | |

| Republicans (Republicanos) | 129,225 | 6.28 | 4 | 11 | 15 | |

| Regionalist League of Catalonia (LRC) | 110,007 | 5.35 | 2 | 20 | 22 | |

| Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) | 38,151 | 1.85 | 1 | 6 | 7 | |

| Agrarians (Agrarios) | 29,975 | 1.46 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Catholics (Católicos) | 26,377 | 1.28 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Carlists (Carlistas) | 19,071 | 0.93 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Catalan Action (AC) | 16,937 | 0.82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) | 13,152 | 0.64 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| National Monarchist Union (UMN) | 6,240 | 0.30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Biscay Monarchist League (LMV) | 3,437 | 0.17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Communist Party of Spain (PCE) | 2,320 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Independents (Independientes) | 54,263 | 2.64 | 1 | 7 | 8 | |

| Other candidates/blank ballots | 37,358 | 1.82 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 2,056,974 | 146 | 263 | 409 | ||

| Votes cast / turnout | 2,056,974 | 65.74 | ||||

| Abstentions | 1,071,954 | 34.26 | ||||

| Non-Article 29 registered voters | 3,128,928 | 65.43 | ||||

| Article 29 non-voters | 1,653,419 | 34.57 | ||||

| Registered voters | 4,782,347 | |||||

| Sources[45][46][47][48] | ||||||

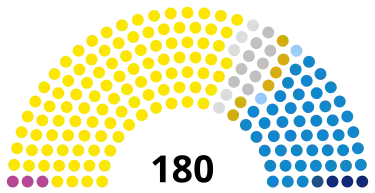

Senate

| ||

| Parties and alliances | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| Liberal Union (UL) | 105 | |

| Liberal Conservative Party (PLC) | 46 | |

| Regionalist League of Catalonia (LRC) | 6 | |

| Republicans (Republicanos) | 3 | |

| Carlists (Carlistas) | 3 | |

| Catholics (Católicos) | 1 | |

| Biscay Monarchist League (LMV) | 2 | |

| Independents (Independientes) | 5 | |

| Archbishops (Arzobispos) | 9 | |

| Total elective seats | 180 | |

| Sources[49][50][51][52] | ||

Aftermath

Notes

References

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 18, 22, 41, 44 & 51–54.

- ^ Martorell Linares 1997, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Martínez Relanzón 2017, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Cabrera, Jesús (22 May 2021). "El discurso de Alfonso XIII en Córdoba que cambió la historia de España". La Voz de Córdoba (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Cruz, José; Roldán Velasco, Roberto Carlos (23 May 2021). "El discurso del Rey". Córdoba (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Primo Jurado, Juan José (23 May 2021). "El Discurso del Círculo". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Muñiz, Teresa (29 December 2023). "El transcendental discurso del Rey". Córdoba (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Gómez Ochoa 1990, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Gómez Ochoa 1990, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Gómez Ochoa 1990, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Royal Academy of History 2022, Cuenca Toribio, José Manuel. Personajes: Antonio Maura y Montaner. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 18–19 & 41.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 38, 42 & 45.

- ^ "El Senado en la historia constitucional española". Senate of Spain (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ a b Law of 8 August (1907), arts. 1–3.

- ^ García Muñoz 2002, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Carreras de Odriozola & Tafunell Sambola 2005, p. 1077.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 1–3, 12–13 & 25.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 27–28.

- ^ Law of 8 August (1907), art. 21.

- ^ a b Law of 8 August (1907), add. art. 3, applying Law of 26 June (1890), trans. prov. 1, applying Law of 28 December (1878), art. 2, applying Law of 1 January (1871), art. 1.

- ^ Law of 8 August (1907), art. 29.

- ^ Rules modifying constituency boundaries:

- Ley dividiendo la provincia de Guipúzcoa en distritos para la elección de Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 23 June 1885. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Ley dividiendo el distrito electoral de Tarrasa en dos, que se denominarán de Tarrasa y de Sabadell (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 18 January 1887. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Ley fijando la división de la provincia de Álava en distritos electorales para Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 10 July 1888. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Ley disponiendo que las primeras y sucesivas elecciones que se verifiquen en la provincia de Zamora se dividirá en siete distritos en la forma que se expresa (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 18 June 1895. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- Leyes aprobando la división electoral de las provincias de León y Vizcaya (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 2 August 1895. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- Leyes aprobando la división electoral en las provincias de Sevilla y de Barcelona (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 5 July 1898. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- Ley mandando que en lo sucesivo sean cuatro los Diputados a Cortes que elegirá la circunscripción electoral de Cartagena (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 7 August 1899. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- Ley estableciendo una circunscripción para elegir tres Diputados a Cortes, que la constituirán los cuatro partidos judiciales de Ayamonte, Hueva, Moguer y la Palma, con todas las poblaciones que de ellos forman parte (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 24 March 1902. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- Ley disponiendo que el territorio de la Nación española que constituye el Archipiélago canario, cuya capitalidad reside en Santa Cruz de Tenerife, conserve su unidad, ateniéndose los servicios públicos en el modo y forma que se determina en esta ley (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 11 July 1912. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- Real decreto disponiendo que la isla de La Palma (Canarias) se divida, a los efectos de las elecciones para Diputados a Cortes, en dos distritos, que se denominarán de Santa Cruz de la Palma y de Los Llanos (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain, at the behest of the Minister of Governance. 20 March 1916. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ Constitution (1876), art. 20.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 21–22 & 53.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 1 & 30–31.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 2.

- ^ "Real decreto disponiendo el número de Senadores que han de elegir las provincias que se citan" (PDF). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish) (76). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: 1021. 16 March 1899.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 1.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 20–21.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 56–59.

- ^ Law of 8 August (1907), arts. 55–58.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 29 & 31.

- ^ Law of 8 August (1907), arts. 4–7.

- ^ Law of 7 March (1880), arts. 1–4.

- ^ Law of 31 July (1887).

- ^ Law of 8 August (1907), art. 24.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 22 & 26.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 4.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), arts. 5–9.

- ^ Constitution (1876), arts. 24 & 30.

- ^ Constitution (1876), art. 32.

- ^ Law of 8 February (1877), art. 11.

- ^ Real decreto declarando disueltos el Congreso de los Diputados y la parte electiva del Senado; disponiendo que las Cortes se reúnan el día 23 de Mayo próximo, y que las elecciones de Diputados se verifiquen en todas las provincias de la Monarquía el día 29 del mes actual, y las de Senadores el 13 de Mayo siguiente (PDF) (Royal Decree). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 6 April 1923. Retrieved 18 August 2025.

- ^ Villa García 2020, pp. 276–287.

- ^ "Resultado de las elecciones de Diputados a Cortes verificadas el 29 de abril de 1923" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "La constitución del Congreso". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 5 May 1923. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Elecciones a Cortes 29 de abril de 1923". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Ayer fueron elegidos ciento ochenta abuelos de la patria". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Voz. 14 May 1923. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "La elección de Senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Época. 14 May 1923. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno se felicita del resultado". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 15 May 1923. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "Las elecciones de Senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Globo. 15 May 1923. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Ley mandando que los distritos para las elecciones de Diputados a Cortes sean los que se expresan en la división adjunta (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom. 1 January 1871. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- Constitución de la Monarquía Española (PDF) (Constitution). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 30 June 1876. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley electoral de Senadores (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 8 February 1877. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley electoral de los Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 28 December 1878. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley enumerando los empleos con los cuales es compatible el cargo de Diputado a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 7 March 1880. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- Ley reformando el art. 4º. de la ley de Incompatibilidades (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 31 July 1887. Retrieved 15 August 2025.

- Ley electoral para Diputados a Cortes (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Regent of the Kingdom p.p King of Spain. 26 June 1890. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- Ley reformando la Electoral vigente (PDF) (Law). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). King of Spain. 8 August 1907. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- Gómez Ochoa, Fidel (1990). "El gobierno de concentración en el pensamiento y la acción política de Antonio Maura (1918-1922)". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (69): 239–251. ISSN 0048-7694. Retrieved 21 August 2025.

- Martorell Linares, Miguel Ángel (1997). "La crisis parlamentaria de 1913-1917. La quiebra del sistema de relaciones parlamentarias de la Restauración". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (96). Madrid: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales: 137–161.

- Martínez Ruiz, Enrique; Maqueda Abreu, Consuelo; De Diego, Emilio (1999). Atlas histórico de España. El Reinado de Alfonso XIII (1902-1931) (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Bilbao: Ediciones KAL. pp. 121–132. ISBN 9788470903502.

- Armengol i Segú, Josep; Varela Ortega, José (2001). El poder de la influencia: geografía del caciquismo en España (1875-1923) (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons. pp. 655–776. ISBN 9788425911521.

- García Muñoz, Montserrat (2002). "La documentación electoral y el fichero histórico de diputados". Revista General de Información y Documentación (in Spanish). 12 (1): 93–137. ISSN 1132-1873. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Carreras de Odriozola, Albert; Tafunell Sambola, Xavier (2005) [1989]. Estadísticas históricas de España, siglos XIX-XX (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 1 (II ed.). Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. pp. 1072–1097. ISBN 84-96515-00-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- Cabo Villaverde, Miguel (2008). "Leyendo entre líneas las elecciones de la Restauración: la aplicación de la ley electoral de 1907 en Galicia". Historia Social (in Spanish) (61): 23–43. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Martínez Relanzón, Alejandro (2017). "Political Modernization in Spain Between 1876 and 1923". Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska, Sectio K. 24 (1). Madrid: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University: 145–154. doi:10.17951/k.2017.24.1.145. S2CID 159328027.

- Villa García, Roberto (2020). "¿Un sufragio en declive?: las elecciones al Congreso de 1923". Historia y Política (in Spanish) (43): 255–290. doi:10.18042/hp.43.09. hdl:10115/27459. ISSN 1989-063X. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Royal Academy of History (2022). "Historia Hispánica". historia-hispanica.rah.es (in Spanish).

- Ruiz Franco, Rosario (2024a). "Historia Contemporánea de España. Reinado de Alfonso XIII (1902-1923). El Desastre de Annual y el Expediente Picasso" (PDF) (in Spanish). Charles III University of Madrid. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- Ruiz Franco, Rosario (2024b). "Historia Contemporánea de España. Dictadura de Primo de Rivera (1923-1930). El "cirujano de hierro": el golpe de Estado de septiembre de 1923" (PDF) (in Spanish). Charles III University of Madrid. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)