1975 Stock Brokerage Commission Deregulation

On May 1, 1975, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) passed a mandate eliminating fixed rate brokerage

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act to amend the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and other laws to remove barriers to competition, strengthen investor protections, and facilitate the establishment of a national market system for securities. |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | May Day, Commission Deregulation of 1975 |

| Enacted by | the 94th United States Congress |

| Effective | May 1, 1975 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Securities Act of 1933, Investment Advisers Act of 1940 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| Gordon v. New York Stock Exchange, Inc., 422 U.S. 659 (1975), Edwards & Hanly v. Wells Fargo Sec. Clearance Corp., 458 F. Supp. 1110 (S.D.N.Y. 1978) | |

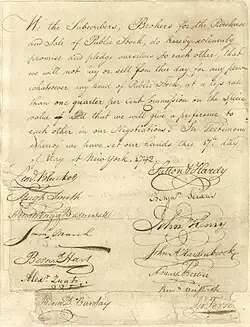

commissions on stock trades, an event that became known as “May Day.” This deregulation ended 183 years of non-negotiable commissions on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).[1][2] Until then, the NYSE had a fixed commission schedule, which all member firms were required to follow charging the same minimum fee (1%–2% of the trade's value) depending on the size of the trade, a practice dating back to the 1792 Buttonwood Agreement.[3]

The change on May Day 1975 transformed Wall Street’s business model by introducing price competition for trading services. Investors, who had previously paid uniformly high fees, soon benefited from lower trading costs, while brokerage firms faced new competition. The decision followed nearly a decade of debate and negotiation involving the SEC, the Department of Justice, leaders of the NYSE, Congress, and major brokerage firms.[4] These discussions addressed growing antitrust concerns, market inefficiencies, and the desire for a more accessible market.[1][3]

Historical background

From its founding in 1792 until May Day, the NYSE enforced a fixed commission for all stock trades. Their rates were formalized into the exchange rules in the early 1800s and remained unchanged for over 150 years.[4] The NYSE intended this policy to preserve order among member firms and ensure uniform earnings, especially for smaller brokers who might otherwise be priced out by competitors.[4]

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the fixed rate commissions system was becoming more strained. Institutional investors were becoming increasingly dominant, demanding more flexible pricing as their large trading volumes showed the inefficiency of fixed commissions.[3] These large-scale investors did not want to pay the same per-share rate as retail investors and sought discounted trading options through non-member firms in so-called “Third Markets”.[3] A notable trigger point was the "Paperwork Crisis" of 1968–1970, which exposed significant weaknesses within brokerage firms, prompting increased scrutiny by regulators.[4] The number of daily transactions doubled between 1965 and 1968, and many firms lacked the capacity to process them.[1] As a result, over 160 firms either failed or consolidated, and the NYSE considered closing on Wednesdays to catch up on record-keeping tasks.[4] This pushed the desire for reform and brought scrutiny from the SEC, which had issued a major report in 1963 recommending structural improvements to securities markets.[1]

In 1967, the Department of Justice Antitrust Division publicly criticized the NYSE's pricing rules, and by 1972, the Nixon administration filed a formal antitrust suit against the Exchange.[4] That same year, NYSE President Robert Haack gave a speech before the House Financial Services Committee in February 1970 arguing that the Exchange must “discard archaic procedures” to remain competitive. This came as a surprise, as Haack was initially opposed to the deregulation.[4]

In September 1973, the SEC announced that fixed commissions would be eliminated by May 1, 1975.[1] This decision came around the same time as the Securities Acts Amendments of 1975 were being worked on by Congress, which allowed the SEC to enforce competitive pricing and build a national market system.[5] Driven by a combination of antitrust concerns, economic inefficiencies, and broader regulatory philosophies in favor of increased market competition.[1][5] Wall Street firms argued that deregulation would destabilize the securities market and harm investors, and industry warnings predicted widespread brokerage failures and market chaos.[2]

SEC motivation

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission's decision to end fixed brokerage commissions was driven by economic, legal, regulatory, and equity-based factors that shaped the agency's belief that uniform pricing was no longer sustainable in modern markets.[1][2] Specifically, the SEC cited investor fairness, market inefficiencies, and barriers to competition as primary concerns.

Investor fairness and market access

The 1975 SEC Annual Report noted that fixed rates “placed unnecessary burdens on investors” and reduced the accessibility of markets for the general public.[1] They were concerned that fixed commission rates were unfair to retail investors and prevented equal access to securities markets due to:

- High entry costs: Fixed commissions often amounted to 1–2% of each transaction, discouraging small investors from entering the market.[3]

- Inequitable structure: Large institutional investors were frequently granted informal rebates or used alternative trading channels to avoid paying full fees, while smaller investors had no access to such privileges.[1][2]

Market inefficiencies

SEC studies showed that competition would encourage firms to become more efficient and improve their quality of service.[1][3] They viewed the fixed-rate model as an obstacle to innovation and improvement within brokerage firms due to:

- Lack of pressure: Protected by fixed pricing, brokers were not incentivized to make operations more efficient or modernize their infrastructure.[4]

- Inflated fees: Full-service brokers made investors pay inflated trading fees that covered not just the cost of executing a trade

,but also the broker's research reports, advice, and perks like expensive lunches or sports tickets, even if the investor did not use those services.[3] - Oligopoly: Fixed commissions created a closed network of NYSE member firms with limited external competition, allowing large brokers to dominate without pricing pressure.[4]

Open market competition

The deregulation aligned with a broader shift in federal policy toward a more competitive market, with the Department of Justice filing a formal antitrust complaint against the NYSE in 1972, arguing that the fixed-rate structure violated price-fixing laws.[4] The SEC faced political and public expectations to promote transparent and competitive financial markets that were compliant with free-market ideals.[5] Regulators began to view the NYSE's pricing model as a cartel-like system that protected large firms at the expense of investors and under the Nixon and Ford administrations, economic policy leaned strongly toward deregulation in multiple sectors (transportation, telecommunications, energy). This era marked a shift where, according to Poser, “the SEC increasingly reflected the deregulatory bias of the political leadership”.[5] This political backing made deregulation a viable and enforceable policy choice.

Data-backed motivation & reflection

The SEC backed its position with internal and external research, concluding that the benefits would outweigh the concerns firms had about the deregulation:

- SEC staff studies in the early 1970s projected that open pricing would reduce transaction costs and increase liquidity across markets. These studies supported the idea that price competition would benefit all investors.[1]

- Gregg Jarrell's 1984 economic analysis showed that trading volume on the NYSE increased significantly following May Day 1975, while average commission rates dropped. According to his findings, commissions declined by roughly 6% per year for two decades after deregulation, contributing to broader market participation and firm diversification.[3]

- Liu's 2008 study between the U.S. and Japan found that the U.S. saw a faster, more impactful increase in trading volume and brokerage service diversification after commission deregulation. Liu concluded that the American experience set a global precedent for how liberalizing commission pricing could drive efficiency and competition.[6]

- Zweig (2015) found that, prior to deregulation, a typical 100-share stock trade incurred a minimum commission of $49, plus a bid-ask spread, totaling roughly 2.5% of trade value. Post-deregulation, the same trade cost less than $10, even before adjusting for inflation.[2]

“May Day”

On May 1, 1975, the Securities and Exchange Commission's Rule 19b-3 came into effect, officially ending fixed-rate commission schedules on all U.S. national securities exchanges. The rule required member firms to independently determine and negotiate commission rates with clients, and the date became known in the industry as "May Day".[1]

Industry preparation & internal guidance

Leading up to May Day, the SEC had given firms nearly 18 months to prepare for the transition, and by April 1975, the NYSE and member firms had begun implementing pricing systems and client communication strategies to comply with the new structure. The SEC had given internal guidance, asking brokerage firms to clarify how they would establish profitability benchmarks, manage research fees, and determine their long-term competitive strategy in a deregulated market.[1]

Legal challenges & industry pushback

Despite this preparation window, in the days before implementation, some firms attempted legal resistance. The Supreme Court case Gordon v. New York Stock Exchange, inc., for instance, attempted to argue that the SEC had no jurisdiction over commission structures, but the case held that the SEC's supervision of fixed commission rates precluded antitrust challenges under the Sherman Act. The court determined that the regulatory framework was intended by Congress to oversee such matters, meaning antitrust laws were inapplicable.[7] The New York Stock Exchange and its member firms also released public statements claiming that deregulation would harm small investors and destabilize the industry. A handful of firms pushed for delays or alternative transitional mechanisms, and Robert Baldwin, chairman of Morgan Stanley, publicly predicted that 150 to 200 firms could fail shortly after May Day due to collapsing margins.[4]

Market stability & reactions

Trading activity on May 1, 1975, went on without disruption. Market operations at the NYSE and other exchanges functioned normally, and there were no significant interruptions to execution or settlement systems. SEC Chairman Ray Garrett Jr. reported in the 1975 Annual Report that the financial condition of broker-dealers remained stable in the immediate aftermath of the transition.[1] Competitive commission pricing came with observable changes in brokerage practices, such as standard commission rates being cut by up to 50%.[3]

Financial industry publications and national news outlets reported on the transition, and initial assessments suggested a smooth transition. Analysts said that while there were new challenges to firm profitability, there are also opportunities for market entry and service differentiation.[8]

Short-term effects

The most immediate effect was the reduction in brokerage commission rates across most major firms, who began offering rate cuts as high as 50% to keep clients.[3] Within months, new firms began taking advantage of the deregulation. Charles Schwab & Co., which had been founded in 1971, launched its first retail branch in September 1975 and began marketing low-cost stock trades to individual investors. Schwab's model reflected the new “discount broker” category where firms offered trade execution without bundled services such as advisory or research.[8] This innovation appealed to retail investors who had previously been priced out of the market due to high fixed commissions.[2]

Some brokers adapted by unbundling their services, offering trade execution separate from research and advice. Others introduced tiered pricing structures based on client size or volume. This era also marked the emergence of financial product specialization, as brokers experimented with fee-for-service advisory models or began to diversify into new product categories like mutual funds.[3] Several smaller broker-dealers soon merged or exited the industry due to margin pressures and increased price transparency.[4]

Long-term effects

Evolving business models

With fixed commissions gone, firms had to adapt to a new environment where price and service differentiation became critical.

- Unbundling of services: Firms moved toward a model where services such as trade execution, research, and advice were priced separately. Merryl Lynch, one of the largest brokerage firms at the time, introduced tiered service models by the late 70s, which contributed to the emergence of fee-based advisory accounts and independent research providers in the 80s and 90s.[8]

- Shift towards wealth management: Companies such as Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs expanded their private client divisions during the 80s, offering personalized financial advice and asset management services to high net-worth individuals.[4][2]

- More integrated sectors: Brokerage, commercial banking, and investment banking became more interconnected as firms diversified through mergers acquisitions, and the establishment of multi financial subsidiaries. Citigroup, created through the merger of Travelers Group and Citicorp, is one example of a conglomerate combining commercial banking, insurance, and securities operations under one corporate umbrella.

- Legal convergence: The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act by the Gramm-Leach-Bailey Act of 1999 formally got rid of the legal separation between commercial and investment banking that had been established during the New Deal era.[5]

Decline in commission costs

Competitive pricing, along with technological advancements steadily reduced transaction fees for both institutional and retail investors. A 1977 SEC study estimated that competitive pricing saved investors about $700 million in fees within the first 20 months after May Day.[3]

Through the following decades, innovations like electronic trading systems and the rise of online brokerage platforms continued to lower trading costs, causing brokerage commissions to decline by about 95% between the early 1970s and late 2000s, from $0.80 to $0.04 per share.[8]

Discount brokers & online trading

By 1979, the SEC recorded 97 registered discount brokers, compared to only a handful before deregulation, and these firms collectively handled nearly 8% of U.S. retail trading volume.[3]

As mentioned earlier, Charles Schwab & Co. expanded rapidly by focusing on telephone-based order placement and reduced commission schedules that undercut traditional full-service competitors.[8] By streamlining operations and focusing on price-conscious investors, Schwab and similar firms laid the foundation for further technological innovation in the sector. The rise of these discount brokers directly paved the way for online trading in the 1990s, as firms adopted internet-based platforms to offer even faster and lower-cost access to markets, significantly expanding retail investor participation.[9]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "SEC Annual Report, 1975" (PDF). SEC Historical Society. 1975. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zweig, Jason (April 30, 2015). "Lessons of May Day 1975 Ring True Today: The Intelligent Investor". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jarrell, Gregg A. (1984). "Change at the Exchange: The Causes and Effects of Deregulation". The Journal of Law & Economics. 27 (2): 273–312. doi:10.1086/467066. ISSN 0022-2186. JSTOR 725577.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Traflet, Janice; Coyne, Michael (2007). "Ending a NYSE Tradition: The 1975 Unraveling of Brokers' Fixed Commissions and its Long Term Impact on Financial Advertising". Essays in Economic & Business History. 25: 131–142. ISSN 2376-9459.

- ^ a b c d e Poser, Norman (2009). "Why the SEC Failed: Regulators Against Regulation". Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law. 3 (2) – via Brooklyn Works.

- ^ Liu, Shinhua (2008-07-01). "Commission deregulation and performance of securities firms: Further evidence from Japan". Journal of Economics and Business. 60 (4): 355–368. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2007.03.005. ISSN 0148-6195.

- ^ "Gordon v. New York Stock Exchange, Inc., 422 U.S. 659 (1975)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2025-05-03.

- ^ a b c d e Silber, Kenneth (May 1, 2010). "The Great Unfixing". ThinkAdvisor. Retrieved May 2, 2025.

- ^ Stefanadis, Chris (2001). "The Evolution of Online Brokers". SternBusiness. Retrieved May 2, 2025.