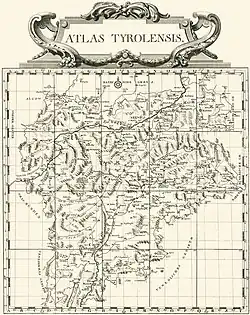

Atlas Tyrolensis

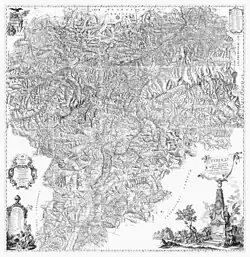

The Atlas Tyrolensis (Tyrol Atlas) is the first geographic map of Tyrol created based on a geodetic survey. It was initiated by the Jesuit priest Ignaz Weinhart in the 1760s–1770s. The authors were Peter Anich from Oberperfuss and his student Blasius Hueber, who, due to their peasant origins and lack of formal education, were also nicknamed Bauernkartografen ("peasant cartographers").

Johann Ernst Mansfeld published the work in 1774 as a decorated copperplate engraving. Due to the large scale adopted (1:104,000), its accuracy, and the size of the area depicted, this map is considered one of the most significant international cartographic achievements of the 18th century[1] and was known "at the time as the most significant and internationally renowned Austrian map."[2] To this day, it remains an important source for Historical geography, Glaciology, and Toponymy of Tyrol.

Description

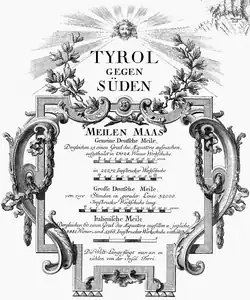

The Atlas Tyrolensis depicts the County of Tyrol, including the ecclesiastical principalities of Brixen and Trent, an area of 26,000 km², represented at a scale of approximately 1:103,800. The map, covering nearly 5 square meters (217.5 x 226 cm), is divided into 20 sheets.[3] Additionally, the work includes an overview map (Registerbogen, scale approximately 1:545,000) with a grid and two explanatory legends for the symbols.[1] However, some symbols used in the map are not included in the legend.[4] The atlas is divided into two sections: the first, Tirol gegen Norden ("Tyrol to the North"), primarily covers present-day North Tyrol, East Tyrol, and the northern part of present-day South Tyrol (Südtirol), while the second, Tirol gegen Süden ("Tyrol to the South"), covers the southern part of present-day South Tyrol and Trentino. These parts seamlessly overlap and are represented as separate units only in relation to their distinct historical formation.[5]

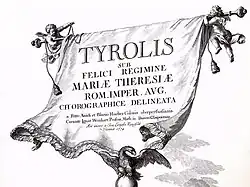

The map features rich artistic decoration created by the engraver Johann Ernst Mansfeld. In the top left corner, the title of the northern section is adorned with a Tyrolean eagle, a goddess, and three putti with game, merchandise, and mineral resources.

In the background, a schematic representation of the Martinswand near Innsbruck symbolizes the landscape of North Tyrol.[6]

At the top right is a legend with the scale in common German miles.

In the bottom right corner is a vexillum, crowning an obelisk with a portrait of Maria Theresa and a Tyrolean eagle; the banner bears the following text:

Tyrol under the fortunate rule of Maria Theresa, august Roman empress, choreographically delineated by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber, farmers of Oberperfuss. Supervised by Ignaz Weinhart, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Innsbruck. Engraved in copper by Johann Ernst Mansfeld, Vienna 1774

— Tyrolis sub felici regimine Mariae Theresiae Rom. Imper. Aug. chorographice delineata a Petro Anich et Blasio Hueber Colonis oberperfussianis Curante Ignat. Weinhart Profess. Math. in Univers. Oenipontana. Aeri incisa a Ioa. Erneste Mansfeld Viennae 1774

At the base of the obelisk, figures with various animals and products symbolize the country’s economic strengths, such as livestock breeding, viticulture, industry, and commerce.[6] Additionally, parts of the South Tyrol landscape are depicted, including the Festung Kofel (Covolo di Butistone, now in Veneto).

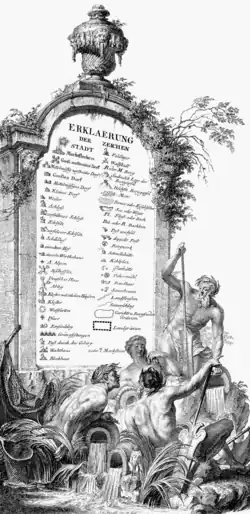

The legend for the southern section is located on the left, below a plinth with three river deities. The symbols depicted in it slightly differ from those in the northern section’s legend, as, among other things, abbreviations are indicated in Italian rather than German (e.g., "M" for "Monte" instead of "B" for Berg). Above the legend are the text Tirol gegen Süden ("Tyrol to the South") and a scale expressed in various units of measure (Wiener Werkschuhe, Innsbrucker Werkschuhe, large German mile, and Italian mile).[6]

Cartographic representation

The representation of territories in the Atlas Tyrolensis follows the cavalier perspective, a form of oblique view typical for the period, which does not distort the elevation plane. Thus, the observer sees the landscape vertically from above, but individual objects from the south at an angle of approximately 45°. To better highlight contours, hatching is used, with the angle of incidence of the fictitious light varying inconsistently between south and west.[1][7]

The over 50 symbols used are largely based on the map of the Kingdom of Bohemia by Johann Christoph Müller (1720).[7]

In the Atlas Tyrolensis, rivers and lakes are relatively accurate, while forests are mapped rather imprecisely, so the value of knowledge about the previous extent of forests is assessed variably.[8][9]

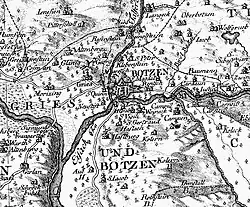

The positions of approximately 570 peaks are accurately indicated with rings, but the terrain shapes are represented only in a relatively schematic form. However, the depiction of remote valleys and icy mountainous regions, which were of little interest before the development of mountaineering, is highly precise for its time. The representation of approximately 1,000 alpine pastures is particularly meticulous, marked for the first time worldwide with a specific symbol. For Anich and Hueber, themselves farmers, these held great importance.[7] Settlements are differentiated by size and legal status (city, market town, village), and individual farms and inns are also highlighted.[9]

Particular attention is given to noble residences and ecclesiastical institutions. These are recorded in a highly differentiated manner; small chapels and completely ruined structures are also noted, as well as some castles that exist only in local folklore.

Regarding roads, they are depicted as carriageable roads, "Samerschläge" (packhorse tracks), and non-carriageable mule tracks; economic aspects such as mining facilities, post offices, mills, mineral springs, vineyards, and charcoal piles are also indicated; conversely, militarily relevant information is kept in the background.[6][9]

However, some military details, such as fortifications, are depicted, which is unusual for the cartography of the time, dominated by military secrecy. Additionally, historical battlefields are represented with their symbols.[7]

The delimitation of Tyrol’s borders in the Atlas Tyrolensis is executed with unprecedented precision, including not only jurisdictional boundaries but also judicial and administrative authorities. However, the borders of Tyrol shown here are biased and reflect the client’s power aspirations more than the political reality. For instance, the ecclesiastical principalities of Brixen and Trent are depicted under Tyrolean administration, although they officially became part of Tyrol only in 1803, without distinction from the County of Tyrol. In Salzburg, related jurisdictions were either not represented or only vaguely indicated (using a graphic symbol otherwise used for disputed and unrecognized borders).[6]

The map is richly annotated, and many geographic names are recorded in writing for the first time. Additional comments are also included, such as the years of landslides or the notation near the Ortler, Ortles Spiz der Höchste im ganzen Tyrol ("Ortler Spiz, the highest in all of Tyrol").[7]

History

Initial situation

Before Peter Anich, the Tyrol area had never been comprehensively mapped. Previous maps of the territory by Wolfgang Lazius (1561), Warmund Ygl (1605), and Matthias Burgklehner (1611) contained significant gaps between valleys.[7]

In the mid-18th century, the officer Joseph von Sperges was tasked with creating a map of South Tyrol (Province of Bolzano) at a scale of 1:121,000, which he could not complete due to his transfer to Vienna. On the recommendation of the Jesuit priest Ignaz Weinhart, around 1759, Sperges commissioned his student Peter Anich to continue the work, which was completed in 1762.[3]

Survey and drafting

In 1760, Ignaz Weinhart mediated a government contract for the survey and mapping of “North Tyrol” as a continuation of Joseph Freiherr von Sperges’ map of South Tyrol.

From 1760 to 1763, Anich, with his assistants, measured the entire territory from scratch, without using pre-existing maps.[7] Unlike his predecessors, such as Sperges, he applied significantly improved triangulation and, deviating from the plane table method previously used in the region, limited himself to measuring angles, later recording them at home. Anich estimated that the inaccuracy of orientations was at most one kilometer, and in the map’s center, it was generally much smaller. Only at the outer edges of Tyrol, which were not measured, are significant inaccuracies found.[11] Although the Atlas Tyrolensis does not include altitude information, it appears that Anich conducted trigonometric height measurements.[8]

With modest remuneration, Anich worked partly with homemade tools (such as a self-made astrolabe[11]) at a rapid pace, with great physical effort and under difficult conditions. He climbed high mountains and worked in adverse weather conditions.

His predecessor Sperges had faced distrust and even physical attacks because people were wary of government personnel. Due to his peasant origins, Anich faced fewer acceptance issues. His simple appearance and peasant attire facilitated access to the local population, which allowed the Atlas Tyrolensis to achieve its wealth of previously undocumented place and village names.[12]

The fact that the Vienna government forced Anich to abandon the planned 1:103,000 scale and redraw the map at the 1:121,000 scale used by Sperges resulted in the loss of two years of work. Additionally, he had to prepare a presentation of the entire Tyrol in nine sheets at a scale of 1:138,000.

Only three sheets, engraved on copper in 1764/1765 but not published, could be completed. In 1764, Anich also began integrating the new addition of “South Tyrol,” essentially present-day Trentino.[1][13] In that year, he began teaching his student Blasius Hueber, who soon independently took over the work of the now seriously ill Anich and, after his death in 1766, continued the survey activities.[12] The survey operations lasted until July 1769; after several months of drafting and correction, in 1770, the map, in sixteenth format, drawn with sepia and ink, with sheets glued onto canvas, measured a total of 145 × 225 centimeters.

The map is still preserved under glass in the Tyrol Provincial Archives.[1]

In 1768, in Vienna, Johann Ernst Mansfeld was commissioned to execute the copper engraving of the map completed by Hueber. The work for the final version repeatedly stalled, and in addition to the corrections Hueber was making, it required several interventions by Ignaz Weinhart.[14] As a result, the sheets to be corrected (particularly for the boundary routes) had to travel back and forth between Vienna and Innsbruck several times, taking several years to complete. This also applies to the index sheet, which was developed starting in 1771 at Weinhart’s suggestion. Also at Weinhart’s proposal, the title Atlas was reinstated, used here for the first time for a map conceived as a unified whole and divided into large, equally sized sheets.[15] Another proposal by Weinhart to include an alphabetical list of place names on the map was rejected by the Vienna government.[14]

The engraving was completed approximately between 1772 and 1773.[8]

Editions and history

In 1774, the Atlas was finally published in the form of 20 sheets and one sheet with an index table. Weinhart’s artistic project with numerous allegorical representations aligns with the tradition of Tyrol maps known up to that point, as well as other major maps of the time, such as the map of Bohemia by Johann Christoph Müller. Thus, it was not considered particularly original, but from an artistic perspective, it is still regarded as one of the most beautiful cartographic representations of the 18th century.[15]

The first edition, with a print run of 1,000 copies that sold out immediately, was reprinted several times in subsequent years, mostly as 20 individual sheets, each approximately 73 × 53 cm. Additionally, the atlas was printed and used as a large wall map.[1] Despite its exceptional quality, the Atlas Tyrolensis could not be recognized internationally as a standard work, and for a long time, modifications were made to older maps still in use.[6]

In 1800/1801, the French General Staff produced a map of Tyrol based on the Atlas Tyrolensis. The French used the atlas, adapted for military purposes, also in the battles of 1809.[7][16]

When the Habsburg hereditary lands were surveyed following Emperor Joseph’s topographic surveys, Tyrol was excluded due to the high quality of the Atlas Tyrolensis, and no further surveys were conducted for a long time. Only in 1823 was a special map of Tyrol, Vorarlberg, and Liechtenstein published, based on the topographic surveys of Francis I, which replaced the Atlas Tyrolensis as the most modern map of Tyrol.[6]

The atlas itself has been reprinted several times, including for its anniversary in 1974[17] and for the first complete “popular edition” at the original scale in 1986.[12]

The historical significance of the Atlas Tyrolensis lies in its unusually large scale and the size of the area shown uniformly, particularly in the new, precise survey methods and accurate drafting, making it one of the most important international cartographic achievements of the 18th century. For the Tyrol region, it was the first map ever created based on geodetic measurements.[1] As such, it was described by glaciologist and mountaineer Eduard Richter as “the effective beginning of the survey of the Eastern Alps” (eigentlicher Anfang der Landesaufnahme in den Ostalpen).[18] Furthermore, the work continues to serve as a precise source for historical-geographic research. The depiction of glaciers, shown correctly for the first time and, for that period, unusually accurately surveyed, allows, in some areas, a fairly precise reading of glacier extents at the time of the survey. Thus, from a glaciological perspective, the Atlas Tyrolensis represents the most significant cartographic work before 1800.[8][10] The Atlas Tyrolensis is still considered an important source for toponymic research, as well as for research on the economic and infrastructural conditions of the former Tyrol.[7][9]

High resolution images

-

Northwest quadrant

Northwest quadrant -

Northeast quadrant

Northeast quadrant -

Southwest quadrant

Southwest quadrant -

Southeast quadrant

Southeast quadrant

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Beimrohr, Wilfried (2006). Tiroler Landesarchiv (ed.). Die Tirol-Karte oder der Atlas Tyrolensis des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber aus dem Jahre 1774 [The Tyrol Map or the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber from the Year 1774] (PDF) (in German). pp. 3–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Kretschmer, Ingrid; Dörflinger, Johannes; Wawrik, Franz (2004). Österreichische Kartographie. Von den Anfängen im 15. Jahrhundert bis zum 21. Jahrhundert [Austrian Cartography: From Its Beginnings in the 15th Century to the 21st Century] (in German). Vienna: Institut für Geographie und Regionalforschung der Universität Wien. p. 80. ISBN 3-900830-51-7.

- ^ a b Beimrohr, Wilfried (2006). Tiroler Landesarchiv (ed.). Die Tirol-Karte oder der Atlas Tyrolensis des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber aus dem Jahre 1774 [The Tyrol Map or the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber from the Year 1774] (PDF) (in German). pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ Kinzl, Hans (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Der topografische Gehalt des Atlas Tyrolensis [The Topographic Content of the Atlas Tyrolensis]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. pp. 65ff. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ Kinzl, Hans (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Der topografische Gehalt des Atlas Tyrolensis [The Topographic Content of the Atlas Tyrolensis]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. p. 173. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Beimrohr, Wilfried (2006). Tiroler Landesarchiv (ed.). Die Tirol-Karte oder der Atlas Tyrolensis des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber aus dem Jahre 1774 [The Tyrol Map or the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber from the Year 1774] (PDF) (in German). pp. 7–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kinzl, Hans (1986). Max Edlinger (ed.). Zur Karte von Tirol des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber [On the Map of Tyrol by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber] (in German). Innsbruck: Tyrolia. p. 18. ISBN 3-7022-1607-3.

- ^ a b c d Kinzl, Hans (1955). Geologische Gesellschaft in Wien (ed.). Die Darstellung der Gletscher im Atlas Tyrolensis von Peter Anich und Blasius Hueber (1774) [The Representation of Glaciers in the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber (1774)] (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Geological Society in Vienna. pp. 91ff. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Beimrohr, Wilfried (2006). Tiroler Landesarchiv (ed.). Die Tirol-Karte oder der Atlas Tyrolensis des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber aus dem Jahre 1774 [The Tyrol Map or the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber from the Year 1774] (PDF) (in German). pp. 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ a b Kinzl, Hans (1955). Geologische Gesellschaft in Wien (ed.). Die Darstellung der Gletscher im Atlas Tyrolensis von Peter Anich und Blasius Hueber (1774) [The Representation of Glaciers in the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber (1774)] (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Geological Society in Vienna. p. 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b Kinzl, Hans (1955). Geologische Gesellschaft in Wien (ed.). Die Darstellung der Gletscher im Atlas Tyrolensis von Peter Anich und Blasius Hueber (1774) [The Representation of Glaciers in the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber (1774)] (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Geological Society in Vienna. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Egg, Erich (1986). Max Edlinger (ed.). Peter Anich [Peter Anich] (in German). Innsbruck: Tyrolia. pp. 12–14. ISBN 3-7022-1607-3.

- ^ Hye, Franz Heinz (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Peter Anich, Blasius Hueber. Die Geschichte des "Atlas Tyrolensis" (1759-1774) [Peter Anich, Blasius Hueber. The History of the “Atlas Tyrolensis” (1759-1774)]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. pp. 18ff. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ a b Hye, Franz Heinz (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Peter Anich, Blasius Hueber. Die Geschichte des "Atlas Tyrolensis" (1759-1774) [Peter Anich, Blasius Hueber. The History of the “Atlas Tyrolensis” (1759-1774)]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. pp. 27f. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ a b Kinzl, Hans (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Der topografische Gehalt des Atlas Tyrolensis [The Topographic Content of the Atlas Tyrolensis]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. pp. 59ff. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ Taormina, Gaetano (1986). Max Edlinger (ed.). Der Atlas Tyrolensis [The Atlas Tyrolensis] (in German). Innsbruck: Tyrolia. p. 16. ISBN 3-7022-1607-3.

- ^ Kinzl, Hans (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Der topografische Gehalt des Atlas Tyrolensis [The Topographic Content of the Atlas Tyrolensis]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien - Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. p. 53. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- ^ Grass, Nikolaus (1994). Zum geistesgeschichtlichen Standort des Atlas Tyrolensis (1774) von Peter Anich und Blasius Hueber [On the Intellectual-Historical Context of the Atlas Tyrolensis (1774) by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber] (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. p. 107.

Bibliography

- Max Edlinger, ed. (1986). Atlas Tyrolensis [Atlas Tyrolensis] (in German). Innsbruck: Tyrolia. p. 16. ISBN 3-7022-1607-3.

- Kinzl, Hans (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Der topografische Gehalt des Atlas Tyrolensis [The Topographic Content of the Atlas Tyrolensis]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien – Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

- Hye, Franz Heinz (1976). Hans Kinzl (ed.). Peter Anich und Blasius Hueber. Die Geschichte des "Atlas Tyrolensis" (1759–1774) [Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber. The History of the “Atlas Tyrolensis” (1759–1774)]. Tiroler Wirtschaftsstudien – Schriftenreihen der Jubiläumsstiftung der Kammer der gewerblichen Wirtschaft für Tirol (in German). Innsbruck: Wagner. ISBN 3-7030-0040-6.

External links

- Beimrohr, Wilfried (2006). "Die Tirol-Karte oder der Atlas Tyrolensis des Peter Anich und des Blasius Hueber aus dem Jahre 1774" [The Tyrol Map or the Atlas Tyrolensis by Peter Anich and Blasius Hueber from the Year 1774] (PDF) (in German). Tiroler Landesarchiv. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2011.