Büyükkale

Büyükkale (turkish for big castle) is a rocky ridge in the Hittite capital Ḫattuša, located in modern-day Turkey. It was inhabited from the late 3rd millennium BC during the early Bronze Age through to the Roman period. Prior to the arrival of the Hittites, a fortified settlement existed during the time of the Hattians, as well as during the period of the Assyrian trade colonies (the Karum period). During the Hittite Empire, the ridge was extensively developed and fortified, serving as the administrative seat of the Hittite Great Kings in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. Fortified settlements also existed on Büyükkale during later Phrygian, Hellenistic, and Roman times. Since the early 20th century, the ridge has been thoroughly excavated, primarily by German archaeologists. The fortress is significant in Hittitology due to the discovery of numerous cuneiform tablets found in the building remains, written in Hittite as well as other languages.

Research history

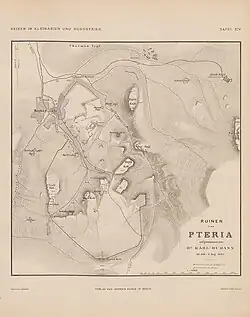

The French traveler Charles Texier, who discovered the ruins near Boğazköy in 1834 and identified them as the remains of ancient Pteria, marked the fortress on his city plan as the Esplanade.[1] The British geologist William John Hamilton, visiting in 1836, was the first to report on the pits or cisterns on the site and the numerous pottery sherds.[2] In Carl Humann's more detailed 1882 plan, the fortress is labeled Böjük Kale.[3] Excavations on Büyükkale began with the French archaeologist Ernest Chantre. After finding individual cuneiform tablet fragments in 1893, he conducted a test pit the following year, likely in the western part of the ridge. These discoveries sparked widespread interest, as they promised further insights into the ancient Near East. In 1905, German Assyriologist Hugo Winckler, along with Theodore Makridi, excavated at Boğazköy until 1907, likely at the same location as Chantre, focusing primarily on cuneiform texts while largely neglecting the architecture. Numerous clay tablets were uncovered, leading Winckler to conclude that the ruins at Boğazköy were those of Ḫattuša, the capital of the Hittite Empire. These unsystematic and unpublished excavations were partially documented by Otto Puchstein, who was present at the time.[4]

From 1907 to 1931, excavations on Büyükkale were halted, partly due to World War I. In 1931, German prehistorian Kurt Bittel, commissioned by the Archaeological Institute of the German Reich (now the German Archaeological Institute) and the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft, resumed excavations at Boğazköy, initially focusing on Büyükkale. Within the next two years, large quantities of cuneiform tablets were unearthed. These finds prompted continued excavations, which now systematically documented architectural remains from various layers. Under Bittel’s direction, with support from the German Archaeological Institute, the German Research Foundation, and various sponsors,[5] excavations continued until 1939 and resumed in 1952 after a war-related interruption, with the collaboration of architect and archaeologist Rudolf Naumann. From 1954 to 1966, Peter Neve led the Büyükkale excavations, taking over the overall direction of Ḫattuša excavations in 1978. His successor, Jürgen Seeher, led from 1994, followed by Andreas Schachner since 2006. Finds and contexts have been regularly published since the early 20th century in the journals Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft and Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft. The first comprehensive architectural survey was published by Peter Neve in 1982, titled Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke.[6]

The finds are displayed in the local Boğazköy Museum, the Çorum Archaeological Museum, and primarily the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

Location

The rocky ridge, composed of Mesozoic limestone, is part of a mountain range that encloses the Budaközü Çayı valley to the east. Oriented from southwest to northeast, the high plateau measures approximately 260 × 150 meters. Its highest point, a rock barrier in the northeast, reaches 1,128 meters above sea level. Before construction, the surface was more rugged than it appears today, having been significantly leveled through building activities and natural processes. The plateau is naturally protected by steep cliffs in the north and east, with gentler slopes in the south and west. It lies in the eastern center of Ḫattuša, at the boundary between the Upper and Lower City.[7] The city wall separating the Lower City from the younger Upper City, known as the Postern Wall, also forms the southern fortification of the fortress. It encircles the old city in a wide arc, reconnecting with the northern fortification of Büyükkale.[8] South of the ridge lies the Südburg, a hill that housed a sanctuary with a hieroglyphic chamber and later a Phrygian fortification. Southwest, where the entrance is located, a modern road passes at the base of the hill, descending from the Lion Gate. Across the road to the west lies the Nişantepe rock with the Nişantaş inscription of Šuppiluliuma II. The ridge offered a commanding view over the Lower City and much of the Upper City.[9]

History

The earliest traces of settlement in Ḫattuša date to the Chalcolithic period in the 6th millennium BC, found on the Büyükkaya ridge north of Büyükkale.[10] Büyükkale itself was inhabited from the late Early Bronze Age, with the earliest evidence being storage pits in the south and southwest of the plateau. Their dating is uncertain but predates 2000 BC. Settlement expansion began thereafter, initially limited to the southern part but featuring fortifications by the 19th century BC. The pre-Hittite Hattians are likely candidates for its inhabitants. The entire city of Ḫattuša, including Büyükkale, was destroyed in a conflagration around 1700 BC by Anitta of Kaniš.[11] Resettlement began about a century later, around 1600 BC, when the city was refounded by Ḫattušili I. Likely due to raids by the Kaska, Ḫantili I constructed the first city wall at the turn of the 17th to 16th century BC, which he claimed was previously unprotected, likely identical to the Postern Wall forming the southern fortification of Büyükkale. Due to throne disputes starting under Ḫantili, the city experienced economic and political decline, exploited by neighbors, leading to another burning and gradual decay. The Proclamation of Telipinu by Telipinu after 1500 BC regulated succession, ending internal conflicts and stabilizing rule, enabling the city’s rebuilding.[12] On Büyükkale, a systematic palace complex was first developed. It was destroyed again after 1280 BC, likely linked to succession disputes between the designated ruler Urḫi-Teššup (Muršili III) and his uncle, later Great King Ḫattušili III.[13] The latter and his son, Tudḫaliya IV, oversaw the reconstruction of the final imperial palace, which was destroyed with the fall of the Hittite Empire around 1180 BC.[14]

From the 8th to 6th centuries BC and during Roman times, the plateau was inhabited and usually fortified but never regained regional significance. No further historical details are known.

Structure

The fortress ridge was developed in multiple construction phases and layers. An initial classification into five layers was established in the 1930s, numbered from top to bottom:

- Layer I

- Layer II – both post-Hittite

- Layer IIIb

- Layer IIIa – both imperial period

- Layer IV – Old Hittite

This classification was later refined and expanded but retained its core structure despite some limitations, such as not fully capturing the sparse Roman and Byzantine periods. The current classification is as follows:

| Layer | Period |

|---|---|

| Byzantine | |

| Roman Imperial | |

| Hellenistic | |

| Ia | Late Phrygian |

| Ib | |

| IIa | Early Phrygian |

| IIb | |

| III | Hittite Empire |

| IVa–b | |

| IVc | Old Hittite |

| IVd | Karum period |

| Va | |

| Vb | |

| Vc | Pre-Hittite |

| Vd–f | |

| Vg | Before 2000 BC |

Each layer may encompass multiple construction phases.[15]

The following description reflects the state of the late imperial period in the 13th century BC (Layer III).

Pre-Hittite period

The earliest evidence includes several round pits dug into the clay in the south and southwest of the plateau, near the later Upper Citadel Court, in the area of later buildings M and N. Varying in size, these pits are 0.25 to 0.95 meters deep with diameters of 0.60 to 1.95 meters, likely used as storage silos and later as refuse pits. Finds include fragments of a Chalcolithic pithos, painted sherds of Alişar-III ware, and monochrome sherds, both handmade and wheel-thrown. Precise dating is not possible, but their origin is attributed to Layer V.[16]

From pre-Hittite layers Vd–g, various foundation remains, primarily in the southern plateau, were identified. Built of rubble stones, their purpose is unclear, though a strong southern wall near the later Citadel Gate Court suggests a defensive structure, indicating a fortified presence. Finds include handmade ceramics, Alişar-III ware, and thin-walled wheel-thrown “flowerpot” ware. Layer Vd includes a spatula-like bronze tool. In Layer Vc, near the later Lower Citadel Court, several houses with clay floors were identified, some retaining stone foundations and mudbrick walls. The largest, with eight rooms across three terraces, yielded two charred door leaves (85 × 180 cm), suggesting it was a residence for a high-status individual. Another building likely had two stories. Finds included pithoi, tableware, hearths, pot stands, a stone mold, a bone pin, seals, burnt grain, and a human skeleton. These structures were destroyed in a fire, dated between 1800 and 1600 BC via radiocarbon dating of wood fragments.[16]

Karum period

From pre-Hittite layers Va and Vb, only sparse foundation remains survive, as they were systematically overbuilt, dismantled, or leveled by Layer IVd. These contained few remnants of hand- and wheel-made ceramics, with uncertain dating. Layer IVd is securely dated to the Karum period. It includes parts of a over four-meter-wide wall at the Lower Citadel Gate, the earliest evidence of fortification, possibly built on older wall debris. Various building remains were excavated in the south and southwest, mostly wall fragments, except for Building I/IVd, measuring 23 × 21 meters with at least twelve rooms, some two-storied, and a courtyard with a hearth. Finds in the courtyard included abundant tableware, half a red deer antler from a meal, and a child’s skeleton, suggesting use as a burial site. Room finds included pithoi, decorated spouted and handled jugs, bowls, painted tower vases, and animal rhyta in lion and duck shapes, both utilitarian and cultic. Other finds included a grindstone, lead sheet, bronze pins, and over 100 clay lumps with seal impressions (1 cm diameter) showing ornaments and stylized figures. Layer IVd dates to the 19th century BC during the Assyrian trade colonies, ending in a devastating fire at the 18th–17th century transition during Anitta’s attack from Kuššara.[17]

Early Hittite period

Layer IVc, from the Old Hittite period, includes settlement remains across the plateau and structures on the southwestern slope. Most buildings on the slope are sparsely preserved, overbuilt by the Postern Wall, the earliest Hittite city fortification, constructed in the final phase of IVc. It extended northwest from Büyükkale, encircling the emerging Lower City, partly overbuilt by modern Boğazkale, and reconnected to Büyükkale’s northern wall.[18] Built without mortar from two roughly dressed rubble stone walls (each ~2.7 m thick) filled with gravel and fieldstones, it had a total thickness of 7.5 meters. At the southwestern base, a gate structure had an inner passage of 3.6 meters and an outer one of 3.8 meters, flanked by two gate chambers (11 m wide, 3.5 m deep in the east, 3.0 m in the west). Finds in this area, mostly redeposited from earlier phases, include two arm-thick clay pipes, closed at one end with a thin nozzle-like perforation, likely used for kiln ventilation due to glass flux at the nozzle.[19]

On the ridge’s surface, only minimal Postern Wall remains are identifiable. A Postern found further east extended 100 meters, a 37-meter-long tunnel built in corbel arch technique with pointed arches, leading from the southeastern base to the later Upper Citadel Gate area. With a steep incline (up to 35 degrees), it ranged from 4.0 to 4.3 meters in height. Continuous settlement is evident only in the southern plateau, built on older layer debris and later leveled or destroyed. Four houses have recognizable foundations or depressions, while others retain only fragments or floors. Three buildings had more than two rooms, and further north, ambiguous building traces may belong to IVc. Notably, at least seven two-room houses, uncommon elsewhere in contemporary Ḫattuša, suggest workshops like forges. The ruler’s seat is presumed in the northeastern part. A key dating artifact is the “Manda” tablet, a cuneiform fragment referencing Ḫattušili I’s reign (16th or late 17th century BC). Resettlement is estimated around 1600 BC, ~100 years after the Karum period’s end. The Postern Wall may be the fortification Ḫantili I (c. 1520 BC) claimed to have built against Kaska attacks.[19]

Imperial period

.jpg)

In layers IVa and IVb, evidence of a palace in the northern plateau emerges. The earliest is House J/IVb, later overbuilt in the early imperial period, located near the later entrance to House D, possibly a substructure for an early audience hall. Also from IVb/a are two terrace walls in the east and north. The northwestern wall, under later buildings E and F, is 85 meters long, built as a casing wall of dressed, partly cyclopean stones, ~3 meters thick, serving as both a retaining wall for southeastern buildings and a foundation for structures above. Southeast, at a 2-meter higher level, building wall fragments were excavated. The second terrace wall, twice as long, lies east near the rock ledge with storage pits, adapting to the rock’s contours with several angles, functioning similarly. Traces of a pillared hall parallel to the eastern wall suggest buildings above. These walls continued as substructures for later palace buildings. A dating clue is a tablet with the Bentešina letter, likely addressed to Ḫattušili III (r. c. 1278 BC), found in overlying debris, serving as a terminus ante quem but not generalizable for all palace buildings, as Layer III construction likely began earlier.[20]

In the southern plateau, remains of buildings (IV/A–H) were excavated within the Postern Wall’s protection in the Lower Citadel Court. Minor gate modifications occurred. Buildings, constructed in phases, initially lacked architectural cohesion but had pathways between them. Later, due to limited space, they formed a dense network of alleys, roads, and channels. House IVb/E, possibly cultic, yielded a painted pair of bull vessels with neck filling holes and nostril spouts, interpreted as libation vessels. Other buildings were likely residential and economic, most with round or square hearths; House F had two ovens. Finds included rhyta (bull and duck), pithoi, small bronze objects, and burnt grain. Architectural comparisons with dated Lower City structures place the start of IVa/b at the late 15th century BC, with the Bentešina letter indicating an end, suggesting a 120–140-year duration.[20]

Late Imperial period

From the late 13th century BC, under Ḫattušili III, the palace ridge underwent monumental expansion. The remains of Layer III are primarily visible today.[21]

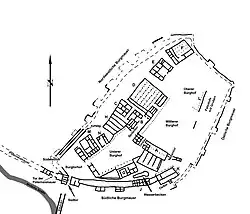

Fortification

The entire plateau was now used for administrative buildings, enclosed by a fortress wall. The southern wall replaced the earlier Postern Wall, shifted upward, while west, north, and east walls adapted to the terrain’s irregularities. The 21 towers or bastions aligned with natural rock outcrops. The massive wall base used rubble masonry, with ashlar only at gates and tower facades, topped with timber framing and mudbrick forming internal rooms. Gates existed in the southwest, south, and east.[22] The main access was the southern gate, reached via a viaduct from the southwest, with its reconstructed stone substructure visible east of the modern road. It supported a high mudbrick structure, possibly timber-covered for horse-drawn carts. The approach led to a four-meter-deep forecourt, followed by two passages (outer: 3 m wide, inner: 4 m) flanked by towers (east: 12 m, west: 8 m), housing a guardroom (west) and staircase to upper floors and battlements (east). Similar to the Upper City’s Lion, Sphinx, and King Gates, it was smaller but featured lion sculptures at the outer passage, with a lion relief fragment found on the slope. Four fragments of a hieroglyphic Luwian inscription stone, likely from the tower bases, were too damaged for dating. The southwest gate was destroyed in Phrygian times during a deep well’s construction, leaving only a threshold and jamb stone, smaller than the southern gate and city walls. It connected directly to the Lower City, used by suppliers and the king for sanctuary visits, near Büyükkale’s sole water source. The eastern gate, between Building K and the northern wall, provided direct access to the upper palace with royal quarters, bypassing lower courts.[23]

The fortress wall formed a continuous ring, except in the southeast, where the western wall met Building K, and the northern eastern wall aligned to create the eastern gate passage. The southern wall was ~7 meters thick, with towers up to 12 meters wide. Other sections varied due to terrain, with a uniform ~5-meter-thick wall, curtains of 14–41 meters, tower widths of 6.9–12 meters, and bastion projections of 3.5–9 meters. Towers consistently overtopped the wall. Depending on single or double-story construction, curtains were 10–12 meters high, towers 14–18 meters. The southern wall rested on the Postern Wall’s substructure, while others sat on shaped bedrock with an outer ledge to prevent slippage. The wall used double-casing timber framing with mudbrick in box construction, with occasional cross-walls forming rooms, possibly accessible. Tower facades used ashlar, and the wall’s top, likely paved with clay slabs, had a battlement walkway.[23]

Dating relies on two textual finds: the Bentešina letter in the fill, indicating construction under Ḫattušili III (c. 1266–1236 BC) or later, and a Tudḫaliya IV (c. 1236–1215 BC) orthostat fragment with a cartouche, confirming continued construction.[23]

Inner structures

Concurrent with fortification, palace expansion utilized the entire ridge, eliminating the southern settlement. Entering via the viaduct through the South Gate, visitors reached the triangular Citadel Gate Court, bordered by the fortress wall in the south and west, with an entrance to the next court in the northeast. A red-paved path, akin to a modern red carpet, marked the official visitor entrance to the ruler. This path continued through the Lower Citadel Court, another gate, and into the Middle and Upper Citadel Courts. The Lower Citadel Court was flanked by colonnaded halls before buildings M, N, and H (northwest) and G and A (southeast), with M and G likely for representative purposes or residences of high officials. Building N, between M and H, was a small gatehouse, where the southwest gate’s ascent ended, linking to the Lower City and water source. Most buildings were at least two-storied, with access typically from the upper floor due to the slope.[24]

In the north corner of the Lower Citadel Court, before Building H, a passage led to the complex of Buildings B, C, and H, running between a connecting structure and Building B, turning west to access the three via a lane. At the turn, a later-added entrance accessed the large representative Building D. Building B, with ten variably sized rooms across multiple levels, yielded 24 cuneiform tablet fragments. Building C, roughly square with six rooms, contained numerous pottery fragments and a hieroglyphic stele naming Tudḫaliya (likely IV), reused as a threshold stone. Its central room, sunken with a water basin impluvium, suggests a cultic function, likely with Building B. Building H, with four long rectangular rooms across two floors, served as a magazine, connected to C via the northwestern retaining wall. The northeastern Lower Citadel Court ended at a gate, flanked by lion sculptures like the South Gate, designed as a ramp or staircase due to the height difference to the Middle Citadel Court. Debris yielded a fallen lion fragment and a partial Tudḫaliya cartouche, attributing the gate to him. The multi-story gate had twelve rooms with ashlar bases.[25]

The Middle Citadel Court, entering the inner palace, was bordered by colonnades on three sides (northwest, northeast, southeast), with Building A and a small gate in the southeast corner forming the southwestern boundary. Northwest, behind the colonnade, Building D (39 × 48 m) initially had 14 rooms, later expanded with a small room at the southeast corner (the side entrance near Building B) and a main entrance forecourt. Six smaller southeastern rooms formed the entrance with side chambers, while a long southwestern room spanned nearly the building’s length. The remaining six long rectangular rooms, one with a smaller chamber, formed a near-perfect square (35.3 × 35.5 m) despite a >6-meter slope. These supported an upper audience hall with five-by-five wooden columns or pillars. Numerous sculpture fragments (lions, bulls) near the entrance and forecourt suggest column bases for a colonnaded hall. The substructure held cuneiform tablet fragments and 280 sealed clay bullae, indicating a representative reception building with an archive and storage.[26]

Building A, the southwestern Middle Citadel Court boundary, covers up to 36 × 34 meters, with upper and lower tracts due to the slope. The upper tract has two long rooms parallel to the court, one with two small chambers, one accessible from the Lower Citadel Court. The lower tract, abutting the Lower Citadel Court, has five long rooms perpendicular to the upper tract. Four larger rooms contained limestone and granite bases with dowel holes, likely for shelves rather than ceiling supports. About 4,000 cuneiform tablet fragments were found in the debris and clay floors, suggesting a magazine and archive, with the upper tract possibly housing administrative rooms or a scribal school. A small gate in the east led to another court, accessible via the eastern fortress gate, where Building K (27.5 × 22.5 m) lies, continuing the western fortress wall. It has a core with three variably sized rooms and eleven chambers in two rows (northwest, northeast), added post-fire. Corner bases in the core suggest shelves, and over 200 tablet fragments indicate an archive, likely with a representative function tied to the eastern gate, possibly with pillared halls.[27]

Northwest of Building K, the South Lane, bordered by K, the fortress wall, Building J, and the backs of A and G, extends as a narrow, steep lane along the wall to the Citadel Gate Court. Originally stone-paved with an underlying channel draining to the western slope, a later 35–50 cm clay layer with canalization was added, and a separating wall was relocated to the western end, with a threshold and door frame excavated. Building J, integrated into the fortress wall, is 20 meters long, protruding 2.5 meters north, with ten small rooms; its southern part collapsed with the wall. A water basin (24.0 m long, 5.0 m wide in the east, 1.5 m in the west) in the South Square contained votive offerings (jugs, cups, bowls), indicating cultic significance alongside water supply.[28]

The southeastern Middle Citadel Court boundary is uncertain, possibly marked by a pillar row. No details are known about the heavily collapsed area between this and the fortress wall.

The Upper Citadel Court, likely separated by a pillar row, has a 24.5-meter-long, up to 2.2-meter-high artificial rock ledge as its southeastern boundary.[29] Pillar bases near and 2 meters before the ledge indicate a pillared hall (L), likely extending south to close the Middle Citadel Court. Building traces at the ledge’s south end suggest a monumental gate with lion sculptures. Two depressions on the ledge, possibly pre-Hittite storage pits or cisterns, have uncertain dating. The court’s northern and northwestern extent is unclear, with no building traces in the open northern area. Buildings E and F lie northwest, but a 5-meter height difference makes their inclusion unlikely. Both are two-storied, accessed from the court side. Building E (26.6 × 22.2 m) has 13 rooms, with the largest entered via a possible colonnaded hall, likely for storage and archives due to tablet fragments. Building F (33.1 × 29.2 m), less preserved, has five parallel long rooms, suggesting a colonnaded hall above, serving as the ruler’s private quarters with views over the Lower and Upper City.[30]

The late imperial period is divided into three phases: IIIc (likely Ḫattušili III, c. 1266–1236 BC), with new buildings on older foundations; IIIb (Tudḫaliya IV, c. 1236–1215 BC), with monumental expansion; and IIIa, with hasty repairs post-fire, likely under Arnuwanda III (c. 1215–1214 BC) and Šuppiluliuma II (c. 1214–1190 BC).[31]

The low density of furnishings and finds suggests an orderly evacuation post-1190 BC, with residents taking valuables and leaving heavy items like tablets. Fire traces in royal palaces likely postdate abandonment.[32]

Wall painting fragments, found near Building G and in southern fortification debris, similar to Upper City Temples 5 and 9, are 0.2–0.55 cm thick with one or two plaster layers, some with white undercoating. Colors include black, white, red, blue, and ochre yellow, with rosette, spiral, and band motifs, dated to the late 13th century BC.[33]

-

Buildings E and F, royal palace

Buildings E and F, royal palace -

Upper Citadel Court with rock barrier

Upper Citadel Court with rock barrier -

Pit (cistern or storage) on the rock barrier

Pit (cistern or storage) on the rock barrier -

Water basin between Buildings G and J

Water basin between Buildings G and J -

Right: Building K and East Gate; left: fortress wall with Building J

Right: Building K and East Gate; left: fortress wall with Building J -

Building G, with Building A in the background

Building G, with Building A in the background

Post-Hittite period

After Ḫattuša’s abandonment in the early 12th century BC, parts like Büyükkaya were resettled by simple Anatolian inhabitants, possibly including Kaska, with wheel-thrown ceramics showing Hittite traits.[34] Büyükkale’s resettlement began in the 8th century BC, with Phrygians confirmed by finds, including inscriptions.

Phrygian settlement

In early phases IIb and IIa (from the 8th century BC), an unfortified settlement spanned the southern plateau to the former Upper Citadel Court, with one- or two-room houses, including pit houses dug into the ground. The ruler’s residence was likely in the upper court area. Most structures were overbuilt later, leaving sparse remains. The end of this early Phrygian phase, often linked to Cimmerian invasions in the late 7th century BC, is disputed by Andreas Schachner, who notes no Cimmerian evidence in Central Anatolia and uncertain dating for Gordion’s destruction.[35] While the Lower City was destroyed, Büyükkale shows no such traces.[36]

In later phases Ib and Ia, the ridge was refortified, forming a complete city with settlement, palace, and walls. Fortification walls in the southwest, south, and southeast followed the Hittite layout but were solid, not box-constructed, and mostly rubble-built, with bricks only at one gate. Tower spacing varied, with curtains up to 35 meters. Towers, likely overtopping the walls, were separate structures, not integrated. The fortification had older and newer gates in the west and southeast, the latter notable for its monumental design reminiscent of Hittite gates, with offering places, reliefs, and a cult niche with a Kybele statue. A staircase from a spring at the southwestern slope led to the southwest bastion.[36]

The inner structures, divided into three sections by two walls (one north-south, another angling east), included a trapezoidal palace in the northern section (former Upper Citadel Court, 30 m east-west, 16–25 m north-south), entered via a five-room vestibule. The central 8 × 11 m room was surrounded by double-row rooms, with economic buildings in the west. Other sections had rectangular workshops, magazines, and administrative or cultic buildings, alongside less regular residential houses. The denser layout followed a path system defined by gates, using only rubble stones, though mudbrick upper floors are possible.[36]

The second Phrygian phase began in the early 7th century BC, ending likely at the 6th–5th century BC transition with the southeast gate’s destruction, though unfortified settlement may have persisted.[36]

Hellenistic and Roman settlement

In the Hellenistic period and Roman period, a fortified settlement existed, with sparse remains including two southeastern and southwestern wall bases without towers, built as casing walls with rubble fill. Adjacent building traces likely indicate guardrooms, with inner wall fragments suggesting residences. Small finds date these to Hellenistic (late 2nd century BC) and Roman Imperial (3rd century AD) periods, with no gap between Phrygian and Hellenistic phases.[37]

Byzantine, Seljuk, and Ottoman finds (coins, ceramics) confirm later human presence, but no architectural evidence remains.

Clay tablets

Ḫattuša yielded 30,000 inscribed clay tablets.[38] Building A’s late-period archive alone accounts for 4,000, likely stored on wooden shelves, possibly upstairs.[39] Buildings E and K also held significant archives. The oldest tablets date to the Assyrian trade colonies, but most are Hittite, written in Hittite, Akkadian, Hurrian, Palaic, Luwian, and Hattian.[40] Texts cover secular and religious topics, including trade contracts (notably from the Karum period), foreign correspondence, treaties, and service or cultic instructions.

No texts directly reference the palace, but the Mešedi text, a service instruction for palace staff, found by Winckler and Makridi in the early 20th century in the western ridge, offers insights.[41] From the early imperial period but applicable to the final phase, it mentions two courts: the Ḫalentuva-House court (ruler’s residence, likely the Upper Citadel Court) and the Mešedi Court (adjacent, for hearings and receptions, likely the Middle Citadel Court). Gates include the “Great Gate” (É ḫilammar, likely from Lower to Middle Court), Kaškaštepa Gate (Middle to Upper Court), and lower and upper gates. The entrance hall of Building D may be the lower gate. The É arkiu, a chapel for the king’s prayers, may be Building C’s sanctuary.[42] Arsenals for weapons storage are noted near gates.[43]

Reference

- ^ Texier, Charles (1839). Description de l'Asie Mineure, faite par ordre du Gouvernement Français de 1833 à 1837, I [Description of Asia Minor, made by order of the French Government from 1833 to 1837, I]. Paris. p. Pl. 73. Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ Hamilton, William John (1842). Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus and Armenia: with some account of their antiquities and geology [Researches in Asia Minor, Pontus, and Armenia: with some account of their antiquities and geology]. London. pp. 391–392. Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ Humann, Carl; Puchstein, Otto (1890). Reisen in Kleinasien und Nordsyrien [Travels in Asia Minor and Northern Syria]. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. p. Plate XIV. Retrieved July 8, 2025.

- ^ Puchstein, Otto; Kohl, Heinrich; Krencker, Daniel M. (1912). Boghasköi, Die Bauwerke [Boghasköi, The Structures]. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 19. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs. pp. 20ff.

- ^ Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter [Hattuscha – In Search of the Legendary Hittite Empire]. Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8.

- ^ Bittel, Kurt (1982). Peter Neve (ed.). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Introduction by the Editor]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. IX–XV. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Schachner, Andreas (2009). "Die Ausgrabungen in Boğazköy-Ḫattuša 2008" [The Excavations in Boğazköy-Ḫattuša 2008]. Archäologischer Anzeiger. 1: 42.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. pp. 103–115. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter [Hattuscha – In Search of the Legendary Hittite Empire] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 44. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. p. 74. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. p. 136. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 2–6. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ a b Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 7–20. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 21–33. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Schachner, Andreas (2009). "Die Ausgrabungen in Boğazköy-Ḫattuša 2008" [The Excavations in Boğazköy-Ḫattuša 2008]. Archäologischer Anzeiger. 1: 42.

- ^ a b Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 34–46. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ a b Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 47–69. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. p. 103. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Occasionally referred to by Neve as West, Southwest, and Southeast Gates.

- ^ a b c Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 76–90. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. pp. 102–115. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 111–118. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 102–107. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 104–111. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 128–130. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. p. 111. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 90–98. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 131–136. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. p. 170. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Jungfleisch, Johannes (2013). Andreas Schachner (ed.). Archäologischer Anzeiger 2013/1. Tübingen–Berlin: Wasmuth. pp. 170–174. ISBN 978-3-8030-2350-6.

- ^ Genz, Hermann (2000). "Die Eisenzeit in Zentralanatolien im Lichte der keramischen Funde vom Büyükkaya in Boğazköy/Hattuša" [The Iron Age in Central Anatolia in Light of Ceramic Finds from Büyükkaya in Boğazköy/Hattuša]. Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Arkeoloji Dergisi (3). Istanbul: 35–54, esp. 40. doi:10.22520/tubaar.2000.0003 (inactive 24 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter [Hattuscha – In Search of the Legendary Hittite Empire] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 326. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8.

- ^ a b c d Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 142–169. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt [Hattuscha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital] (in German) (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. p. 162. ISBN 975-8070-48-7.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. p. 106. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- ^ Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter [Hattuscha – In Search of the Legendary Hittite Empire] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. p. 153. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8.

- ^ Güterbock, Hans G.; van den Hout, Theo P. J. (1991). The Hittite Instruction for the Royal Bodyguard. Chicago: The Oriental Institute. ISBN 0-918986-70-2.

- ^ Popko, Maciej (2003). "Zur Topographie von Ḫattuša: Tempel auf Büyükkale" [On the Topography of Ḫattuša: Temples on Büyükkale]. In Harry A. Hoffner (ed.). Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner, Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Eisenbrauns. pp. 315–323. ISBN 978-1-57506-079-8.

- ^ Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966 [Büyükkale – The Structures. Excavations 1954–1966]. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.; Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter [Hattuscha – In Search of the Legendary Hittite Empire] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. pp. 147–150. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8.

Further reading

- Neve, Peter (1982). Büyükkale – Die Bauwerke. Grabungen 1954–1966. Berlin: Gebr. Mann. ISBN 978-3-7861-1252-5.

- Bittel, Kurt (1983). Hattuscha – Hauptstadt der Hethiter. Geschichte und Kultur einer altorientalischen Großmacht. Cologne: DuMont. ISBN 3-7701-1456-6, pp. 87–132.

- Seeher, Jürgen (2002). Hattuscha-Führer. Ein Tag in der hethitischen Hauptstadt (2nd revised ed.). Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. ISBN 975-8070-48-7, pp. 102–115.

- Popko, Maciej (2003). "Zur Topographie von Ḫattuša: Tempel auf Büyükkale". In Harry A. Hoffner (ed.), Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner, Jr: On the Occasion of His 65th Birthday. Eisenbrauns, pp. 315–323. ISBN 978-1-57506-079-8.

- Schachner, Andreas (2011). Hattuscha – Auf der Suche nach dem sagenhaften Großreich der Hethiter. Munich: C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-60504-8, pp. 71–82.

- Schachner, Andreas; Becker, Jörg (2023). "Neue Forschungen auf der hethitischen Königsburg Büyükkale (2021–2022) und ihre veränderte Stellung im urbanen System von Hattuscha". In Dirk Wicke; Joachim Marzahn (eds.), Zwischen Schwarzem Meer und Persischem Golf. 125 Jahre Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Darmstadt: wbg Philipp von Zabern in Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, pp. 96–104. ISBN 978-3-8053-5367-0.