Canu Cadwallon

| Canu Cadwallon | |

|---|---|

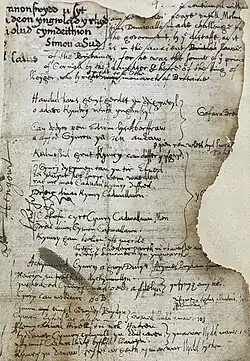

'Gofara Braint' and ll. 26b-28, 40, 51i-56iv of 'Moliant Cadwallon', from NLW MS 9094, p. 9, in the hand of Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt[1] | |

| Author(s) | ?Afan Ferddig ('Moliant Cadwallon' and 'Gofara Braint') |

| Compiled by | Robert Vaughan (Hengwrt MS 120) |

| Language | Middle Welsh |

| Date | ?7th c. ('Moliant Cadwallon' and 'Gofara Braint') ?9th/10th c. ('Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan') |

| Manuscript(s) | list:[2]

|

| First printed edition | Gruffydd 1978 |

| Genre | panegyric, elegiac, and antiquarian poetry |

| Setting | Wales, Deira, Bernicia, Elfed |

| Period covered | Migration-period Britain |

| Personages | Main subjects: Cadwallon ap Cadfan Edwin of Northumbria Implied: |

Canu Cadwallon (Welsh pronunciation: [ˈkanɨ̞ kadˈwaɬɔn]) is the name given by R. Geraint Gruffydd and subsequent scholars to four Middle Welsh poems associated with Cadwallon ap Cadfan, king of Gwynedd (d. 634 AD). Their titles come from the now-lost book entitled Y Kynveirdh Kymreig 'The Earliest Welsh Poets' (Hengwrt MS 120), compiled by the seventeenth-century antiquarian Robert Vaughan of Hengwrt. Later catalogues derived from this manuscript preserve the titles of these poems. Three of the four poems concerning Cadwallon were copied in other texts.[3] One surviving poem is called 'Moliant Cadwallon' by modern scholars or 'Cerdd y Cor a'r Gorres' in the catalogues of Vaughan's manuscript. Fifty-six lines of the poem survive. It appears to refer to events just before the Battle of Hatfield Chase (Old Welsh: Gueith Meicen) in 633, as Cadwallon's final victory over Edwin of Northumbria is not mentioned in the poem.[4] After narrating Cadwallon's expulsion of the English from Gwynedd and possibly his presence at the Battle of Cirencester, the poet exhorts the king to take the fight to Edwin, 'set York ablaze' and 'kindle fire in the land of Elfed'.[5]

There are also two elegies for the king, with one known as 'Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan', and the other as 'Gofara Braint'. The former poem lists Cadwallon's battles and ends with a reference to his death in the Battle of Heavenfield (Old Welsh: Cant Scaul) in 634, but is thought to be ninth- or tenth-century at the earliest, based on its similarities to other early Welsh 'saga' literature like Canu Heledd and Canu Llywarch Hen.[6][7] 'Gofara Braint' survives only in five lines, and refers to Edwin's head being brought to the court of Aberffraw after the battle of Hatfield Chase.[8] The last poem, titled 'I Gadwallon ap Cadfan, brenin Prydain' by Vaughan, is completely lost.[9] Were this poem earlier than 'Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan', it may have informed some of the content of that poem, perhaps together with the lost sections of 'Gofara Braint'.[10]

There is no author given to any poem in the manuscripts, though the Welsh Triads give the name of Cadwallon's chief poet as Afan Ferddig.[11] Excepting one copy of 'Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan' which survives in the Red Book of Hergest, the three surviving poems exist only in seventeenth-century manuscripts.[12] Nevertheless, scholars of medieval Welsh literature generally regard 'Moliant Cadwallon' as a genuine seventh-century composition, which would make it one of the oldest works in Welsh literature alongside those attributed to Aneirin and Taliesin.[13][14] While not edited as part of Canu Cadwallon, there is also a fragmentary verse in Peniarth MS 21 supposedly composed by Cadwallon ap Cadfan which narrates an episode of his exile in Ireland.[15]

Historical background

Cadwallon ap Cadfan is a very well-attested monarch by the standards of the seventh century in Wales. According to the tenth-century Harleian genealogies, his father was Cadfan ab Iago and his great-great-great-grandfather was Maelgwn Gwynedd.[16][17][a] In the fifteenth-century genealogical tract Bonedd yr Awyr, Cadwallon's mother is given as Tandreg Ddu, daughter of Cynan Garwyn and sister of Selyf ap Cynan, who was slain by Æthelfrith at the Battle of Chester in c. 615.[17][18][19][b] Cadwallon came to power in Gwynedd c. 625 following his father's death, and commissioned a Latin tombstone for Cadfan which still survives.[17][c] Besides this poetry, the main sources for Cadwallon's life are Adomnán's Vita Columbae (c. 697-700) and Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (c. 731), as well as some entries in the Welsh Annals. However, Adomnán only narrates events leading to the battle of Heavenfield concerning Oswald, who grew up in Adomnán's monastery of Iona. He reports that Columba appeared to Oswald in a dream on the night before the battle and encouraged the young king, promising that God would grant him victory over Cadwallon, killer of his uncle Edwin.[17][21]

Bede's account of Cadwallon is problematic because Cadwallon opposed Edwin of Northumbria.[17][19] Edwin is a main protagonist of Bede's narrative since on Easter 627 he accepted baptism, the first Northumbrian monarch to have done so.[22] Bede reports that Edwin ruled over 'all the inhabitants of Britain, English and Britons alike, except for Kent... he even brought under English rule the Mevanian Islands (Anglesey and Man) which lie between Ireland and Britain and belong to the Britons.'[17][23] The Welsh Annals record that Cadwallon was besieged on insula Glannauc in 629.[17][24] This must refer to a final stage in Edwin's conquest of Anglesey, but the date should be corrected to 631 or 632, given that the Welsh Annals record events three years too early, such as Edwin's death in 633.[17][25][26] There are later Welsh traditions suggesting that Cadwallon was for a time an exile in Ireland, and so he may have gathered support there to recover his kingdom.[27][28] This may be paralleled by the exile in the Northern Uí Néill- and Dál Riata-sponsored monastery of Iona of Oswald and Oswiu, sons of Æthelfrith and therefore also threats to Edwin's rule.[29]

Under unclear circumstances, Cadwallon returned to Britain and, together with his junior ally Penda of Mercia, slew Edwin on 12 October 633 at the battle of Hæthfelth, probably Hatfield Chase.[17][30][31] Hatfield Chase would have been in the kingdom of Elfed until its conquest by Edwin in c. 620, and was situated between Deiria, Mercia, and Lindsey.[32] The battle is also recorded in the Welsh Annals (as Gueith Meicen), in the Annals of Tigernach, and in the Annals of Inisfallen.[25][33] Bede refers to Cadwallon's rule over Northumbria as the 'ill-omened' year, and calls him a 'savage tyrant' of 'outrageous tyranny', 'even more cruel than the heathen (i.e. Penda)'.[17][30][34] He even suggests that Cadwallon was 'meaning to wipe out the whole English nation from the land of Britain' and 'spared neither women nor innocent children'.[17][30] Cadwallon slew Edwin's cousin and successor in Deira, Osric, as well as his nephew Eanfrith, son of Æthelfrith by Edwin's sister Acha. Eanfrith succeeded Edwin to Bernicia, and was slain whilst entreating Cadwallon for peace.[17][34][d]

Ultimately, Cadwallon was in turn killed by Oswald, Edwin's nephew and Eanfrith's brother, sometime in 634.[17] Oswald returned from his own exile at the head of an army 'small in numbers', but still triumphed.[34] This was at Hefenfeld (Latin: Cælestis campus), recorded as Cantscaul in the Welsh Annals and the Historia Brittonum, where Oswald is called Oswald Lamnguin 'O. Bright-blade'.[25][37][38]

The manuscripts

It appears that Robert Vaughan (d. 16 May 1667) sought to assemble all poetry sung to or about Cadwallon.[3] Vaughan was a descendant of Cadwgan, son of Bleddyn ap Cynfyn, and a native of Dolgellau. His maternal uncle Robert Owen mortgaged the manor home of Hengwrt to Vaughan's father, Hywel.[39] Vaughan's pursuit of Welsh antiquities continued unperturbed by the tumults of the seventeenth century.[39] He was close to other antiquarians of the period such as Dr. John Davies, William Maurice, and John Jones of Gellilyfdy.[39] When John Jones died in c. 1658, Robert Vaughan came into possession of all his manuscripts, and curated a great library at Hengwrt, 'the finest collection of Welsh manuscripts ever assembled by an individual'.[39] This extensive collection provided Vaughan with ample material from which to compile poetry concerning Cadwallon.

One manuscript (Hengwrt MS 120) was written in order to collect the earliest specimens of Welsh poetry, and was titled Y Kynfeirdh Kymreig 'The Earliest Welsh Poets'.[3] Unfortunately, it has since been lost, but William Maurice and Robert Vaughan himself wrote catalogues of the manuscripts in the Hengwrt library which preserve the titles of the poems therein.[40] Vaughan gave the poems concerning Cadwallon the following titles:

- 'Gofara [?] Braint'

- 'Cerdd y Cor a'r Gorres'

- 'I Gadwallon ap Cadfan, brenin Prydain'

- 'Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan'[3]

Only two folios of Hengwrt MS 120 survive, bound in a manuscript of Lewis Morris (BL Add. MS 14907).[41] However, these two pages preserve much of the material of 'Cerdd y Cor a'r Gorres', known as 'Moliant Cadwallon' by modern scholarship.[3][42] NLW MS 9094, a compilation of Vaughan's notebooks on British history, contains four and a half lines of this poem which appear in BL Add. MS 14907, six which are absent in BL Add. MS 14907, and the first five lines of 'Gofara Braint'. These lines were copied into NLW MS 9094 because he interpreted the poems as referencing 'Cymru' as a place-name, though the word might instead stand for Cymry 'the Welsh', since the two words were identical in Middle Welsh.[3][43] Two folios of this manuscript have dates of 1652 and 1658, and the latter part of the manuscript was probably written while Vaughan was working on a chronology of British history for Archbishop Ussher.[44]

The third poem in this list, 'I Gadwallon ap Cadfan, brenin Prydain' is completely lost. The fourth poem, 'Marwnad Cadwallon ap Cadfan', is the only poem to survive in a complete form, in the fourteenth-century Jesus College MS 111 and in BL Add. MS 31055, written by Thomas Wiliems.[3]

The poems

'Moliant Cadwallon'

The most important of the poems edited as part of Canu Cadwallon by R. Geraint Gruffudd is known as 'Moliant Cadwallon'. This is in contrast to Robert Vaughan, who entitled it 'Cerdd y Cor a'r Gorres' ('Song of the Dwarf and the Dwarfess') in Hengwrt MS 120. This title is difficult to understand as there are no reference to dwarves in the poem. R. Geraint Gruffydd suggested that a copyist at some point in the transmission of the poem may have mistook the occurrence of "Efrawg" in the poem as referring to the father of Peredur, in whose eponymous story there exists a pair of dwarfs who prophesy the young knight's future.[45][46] Sir Ifor Williams therefore retitled the poem 'Moliant Cadwallon' (Praise of Cadwallon).[47] This poem is 50 lines in the surviving folios of Hengwrt MS 120 bound in BL Add. MS 14907, while six further lines are copied in NLW MS 9094. Because it survives only in fragments, R. Geraint Gruffydd suggested the original may originally have had at least eighty lines, while John T. Koch proposed it may have been even longer.[48][43]

Notes

- ^ [§1]: Catgollaun map Catman map Iacob map Beli map Run map Mailcun.[16]

- ^ [§28b]: Mam Gatwallawn ap Katfan, Tandreg ddu ferch Gynan garwyn.[20]

- ^ Cadfan's date of death is not known, but it is likely that he died before Cadwallon became politically active. See Thornton 2004.

- ^ Were Selyf really Cadwallon's uncle, this may also have been revenge for the Battle of Chester in which Eanfrith's father Æthelfrith killed Selyf.[35] More practically, it was a ruthlessly pragmatic destruction of dynastic rivals.[36]

References

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, pp. 30

- ^ Gruffydd 1978

- ^ a b c d e f g Gruffydd 1978, p. 26

- ^ Koch 2013, p. 218

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 191, 192, ll. 37n, 51an.

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, p. 35

- ^ Rowland 1990, pp. 169–173

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, pp. 41–2

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, pp. 26–7

- ^ Koch 2013, p. 7, note 16

- ^ Bromwich 2014, pp. 20–21, §11

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, pp. 28–31, 36–38, 42

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, pp. 27–29

- ^ Rodway 2013, p. 14

- ^ Thomas 1987

- ^ a b Guy 2020, p. 334

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Charles-Edwards 2004

- ^ Bartrum 1966

- ^ a b Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 345

- ^ Bartrum 1959, p. 91

- ^ Anderson & Anderson 1991, pp. 14–15, §8a-9a

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 186–87, ii.14

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 148–49, ii.5

- ^ Morris 1980, p. 86, s.a. 629

- ^ a b c Morris 1980, p. 86, s.a. 630

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 169–170

- ^ Bromwich 2014, pp. 62–5, §29

- ^ Haycock 2014, 6.17-88

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 172–73

- ^ a b c Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 202–207, ii.20

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 425

- ^ Koch 2013, p. 175

- ^ Koch 2013, p. 174

- ^ a b c Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 212–15, iii.1

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 163, n. 16

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 179–81

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 215–19, iii.2

- ^ Morris 1980, pp. 38, 79, §64

- ^ a b c d Jones 1959

- ^ Morris 2000, p. 261

- ^ Thomas 1970

- ^ Koch 2013, pp. 161–2

- ^ a b Koch 2013, p. 162

- ^ Huws 2022, pp. 241–2, s.v. NLW 9094A

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, p. 27

- ^ Goetinck 1976, p. 12, ll. 26, 28

- ^ Williams 1933, pp. 23–4

- ^ Gruffydd 1978, p. 28

Bibliography

- Anderson, Alan Orr; Anderson, Marjorie Ogilvie, eds. (1991). Adomnán's Life of Columba. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bartrum, Peter (1959). "Bonedd yr Arwyr". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 18. University of Wales Press: 229–252.

- Bartrum, Peter, ed. (1966). Early Welsh Genealogical Tracts. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Bromwich, Rachel, ed. (2014). Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain (4th ed.). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9781783161454.

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2004). "Cadwallon [Cædwalla] ap Cadfan (d. 634), king of Gwynedd". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4322. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas (2013). Wales and the Britons, 350-1064. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198217312. IA walesbritons35010000char.

- Colgrave, Bertram; Mynors, R. A. B., eds. (1969). Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press. IA x-bede-s-ecclesiastical-history.

- Goetinck, Glenys Witchard (1976). Historia Peredur vab Efrawg. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708326206.

- Gruffydd, R. Geraint (1978). "Canu Cadwallon ap Cadfan". In Bromwich, Rachel; Jones, R. Brinley (eds.). Astudiaethau ar yr Hengerdd: Studies in Old Welsh Poetry (in Welsh). Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 9780708306963.

- Guy, Ben (2020). Medieval Welsh Genealogy: an Introduction and Textual Study. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783275137.

- Haycock, Marged (2013). Prophecies from the Book of Taliesin. Aberystwyth: CMCS Publications. ISBN 9780955718274.

- Huws, Daniel (2000). Medieval Welsh Manuscripts. Aberystwyth: National Library of Wales. ISBN 0708316026.

- Huws, Daniel (2022). A Repertory of Welsh Manuscripts and Scribes c.800 – c.1800. Vol. 1. Aberystwyth: Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies / National Library of Wales. ISBN 1862251215.

- Jones, Evan David (1959). "VAUGHAN, ROBERT (1592? - 1667), antiquary, collector of the famous Hengwrt library". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- Koch, John T., ed. (2013). Cunedda, Cynan, Cadwallon, Cynddylan: Four Welsh Poems and Britain 383-655. Aberystwyth: Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies. ISBN 9781907029134.

- Morris, John, ed. (1980). Nennius: British History and The Welsh Annals. London: Phillimore. ISBN 9780847662647.

- Rodway, Simon (2013). Dating Medieval Welsh Literature: Evidence from the Verbal System. Aberystwyth: CMCS Publications. ISBN 9780955718250.

- Rowland, Jenny, ed. (1990). Early Welsh Saga Poetry: A Study and Edition of the Englynion. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 9780859912754.

- Thomas, G. C. G. (1970). "Dryll o Hen Lyfr Ysgrifen". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 23. University of Wales Press: 309–16.

- Thomas, G. C. G. (1987). "A verse attributed to Cadwallon fab Cadfan". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 34. University of Wales Press: 67–70.

- Thornton, David E. (2004). "Cadfan ab Iago (fl. c. 616–c. 625), king of Gwynedd". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4314. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Ifor (1933). "Hengerdd: Moliant Cadwallon; Darogan". Bulletin of the Board of Celtic Studies. 7. University of Wales Press: 23–32.