Cezar Bolliac

Cezar Bolliac | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Bolliac in 1870 | |

| Born | 23 or 25 March 1813 Bucharest, Wallachia |

| Died | 25 February 1881 (aged 67) Bucharest, Principality of Romania |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1835–1876 |

| Genre | |

| Literary movement | |

| Signature | |

| |

Cezar or Cesar Bolliac, also known as Boliac, Boliacu, Boliak and Boleac (transitional Cyrillic: ЧeсарȢ БoliaкȢ;[1] 23 or 25 March 1813 – 25 February 1881), was a Wallachian and Romanian writer, scholar, and political figure. Born to non-Romanian parents, he joined the local aristocracy, or boyardom, by adoption into the Pereț family. He was briefly a cadet in the Wallachian military forces, but resented the Russian Empire, which had brought Wallachia into its sphere of influence; he took up writing and publishing, and for a while edited a literary magazine called Curiosul—bridging neoclassicism and romanticism. Like other Romanian liberals and Freemasons, Bolliac fought the Russian constitutional arrangement, or Regulamentul Organic, seeing it as a remnant of feudalism. He was therefore caught up in the anti-Russian conspiracy of 1840, and was detained on orders from Prince Alexandru II Ghica. He was ultimately released through the intervention of other Ghica family members, who remained his friends and protectors.

Upon his return, Bolliac continued to test censorship, inventing a style of social poetry that favored the exploited peasantry, and expressing sympathy for the Romani underclass, which had been enslaved by the boyars. He discarded liberalism for utopian socialism, and then, briefly, for a variant of communism; he combined such views with Romanian nationalism, moving it from romantic to left-wing variants. Reaching out to fellow Romanian nationalists in Moldavia and throughout the Austrian Empire, he became involved with researching the origin of the Romanians, performing his first archeological digs along the Danube and in the Southern Carpathians; the landscape provided him with inspiration for romantic elegies, which endure as some of his best works as a poet. Bolliac was an increasingly sarcastic critic of Westernization, earning praise for his journalistic wit, and a rediscoverer of Romanian folklore. He became convinced that the Romanians were primarily descendants of the Dacians—a romantic and post-romantic ideology that was later taken up by Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, and mutated into Dacianism.

Under Prince Gheorghe Bibescu, who embraced nationalism, Bolliac was a poet laureate and a public prosecutor. This did not prevent him from participating in the liberal conspiracy that ultimately became the Wallachian revolution of 1848. He entered the provisional government that toppled Bibescu, also serving the cause as a journalist and propagandist. Involved on the abolitionist side of revolutionary politics, he allegedly embezzled the financial contributions that slaves owed upon their release. In late 1848, the Ottoman Empire restated its control of Wallachia, arresting the rebels—Bolliac was deported with various of his colleagues to Orschowa, whence they either escaped or were allowed to leave. He sought refuge among the Romanians of Austrian Transylvania; deep into 1849, he supported forming a revolutionary alliance with the breakaway Hungarian State, and, alongside his colleague Nicolae Bălcescu, approved of the Hungarian–Romanian pacification act. He fled the Russian invasion, reaching Istanbul; once there, he came to be distrusted by both the Romanian and Hungarian exiles—viewed as a fanatic by the former, and alleged by the latter to have stolen diamonds obtained from the Zichy family.

Evading prosecution by the Ottomans and the Austrians, Bolliac spent the years 1850–1857 in Paris; here, he was won over by the cause of Moldo–Wallachian unionism, as a preliminary step to establishing a Greater Romanian, or "Dacian", state. He popularized this cause to an international audience during the Crimean War, returning to Wallachia just as the war had ended. He was involved in creating the United Principalities (in 1859), suggesting that Moldavia's Alexandru Ioan Cuza be selected as Domnitor. Bolliac also endorsed the more radical points on Cuza's agenda, including land reform, and, as head of the National Archives, collected documents allowing for the secularization of monastery estates. He opposed both Cuza's other political stances (to the point of being imprisoned for lèse-majesté) and the "monstrous coalition" that had been formed against the Domnitor. He spent most of the 1860s involved in political quarrels, often carried through his newspaper, Trompeta Carpaților. Discarding socialism for economic nationalism, Bolliac also embraced violent antisemitism; he initially also opposed the foreign-born ruler, Carol of Hohenzollern, but later found a role for the monarchy in his political vision, copying Bonapartism. Though he made important discoveries at Zimnicea and elsewhere, he came to be widely ridiculed for his drift into pseudoarchaeology, and also shamed, though never prosecuted, as an alleged child sexual abuser. He died after a losing battle with paralysis, leaving a tarnished legacy—though regarded as a hero by the communist regime, especially in the 1950s, it was through his supposed compatibility with Marxism.

Biography

Early life

Bolliac was born in Bucharest, the Wallachian capital, on 23[2] or 25[3][4] March 1813. At the time, and for another four decades, Romanian-speaking Wallachia was governed as an autonomous principality within the Ottoman realm. Cezar's mother was Zinca Kalamogdartis, and his father was a physician and political adventurer, Anton Poleac, Boliaco or Bogliaco. Little is known about the latter, though he is tentatively identified as a member of Mikhail Kutuzov's retinue, present in Wallachia during the Russian invasion of 1812.[5][6] He is widely believed to have had Italian origins,[7] but was also described as Jewish.[8] Tradition holds that he was born in Salonika,[9] though, as researcher Dumitru Popovici argues, this did not imply that he ever belonged to the Greek community.[10] Researcher George Vlad ascribes such origins to Zinca ("a Greek lady, and apparently a beautiful one, hence her two or three marriages").[11]

Anton was absent from his son's life after 1813, having "mysteriously disappeared" from all public records.[12] Cezar was raised for a while by an old lady, possibly his maternal grandmother. She sponsored his education at the Greek school of Boteanului mahala, in what was then a Hellenized, Phanariote-ruled, city of Bucharest.[13] The young boy was effectively adopted by Stolnic Petrache Pereț (or Peretz), who married Zinca.[5][12][14] His new family belonged to the local aristocracy, or boyardom, but had only been promoted into its ranks c. 1829—having acquired land at Stoenești in Vlașca, and townhouses in Giurgiu.[15] By Bolliac's own admission, he himself was subsequently inducted into the upper class, and afforded some political and judicial privileges.[16] When in Bucharest, he inhabited a large townhouse on Podul Mogoșoaiei, near the area currently known as Revolution Square.[17] Bolliac preserved a more traumatic memory of his encounter with slavery, which was by then reserved for the bulk of Wallachia's Romani groups. Pereț owned several house-slaves, a matter which conflicted with the boy's developing humanitarianism; on one occasion, with his parents absent, he allowed the slaves to experience a full day of freedom at his expense.[18]

Bolliac attended the Saint Sava College, where teachers included a future conservative foe, Ion Heliade Rădulescu.[19] It was at this stage that Wallachia and neighboring Moldavia became dominions of the Russian Empire, under a constitutional arrangement known as Regulamentul Organic. Aged seventeen, Bolliac joined the Wallachian military forces as a nominal Junker, but left after a very brief interval—possibly because he felt out of place in that disciplined environment, which stifled his literary calling.[20] During his time under arms, he had befriended several men who would go on to serve radical causes—including Ioan Câmpineanu.[21] He recalled that his first serious writing was done in 1834, at Stoenești, but this is doubtful—as is his claim to have studied in Paris in 1831–1833.[22] Also then, he had a row with Zinca, after she had mistreated one of the Romani slaves at Stoenești.[23]

At the time, Alexandru Ghica had been appointed Prince of Wallachia under Ottoman and Russian supervision. Initially, Bolliac benefited: he was a personal friend of Alexandru's brother, the Great Ban Mihalache Ghica, whom he always regarded as an intellectual leader and an outstanding antiquarian.[24] Bolliac's first known writings date from 1835, when he had joined Heliade and Costache Aristia's Philharmonic Society. Published with philosophical poems in that group's literary collection, he was also credited as the author of novellas and plays, though these were not printed at that stage.[25] He was close friends with Heliade, who would later make Bolliac into the object of a critical essay, probably the first on the history of Romanian literature; it described Bolliac as the group's "enfant terrible".[26]

In 1836, Bolliac and Constantin Gh. Filipescu founded a magazine called Curiosul ("The Inquisitive"), which carried his translations from Byron and Pushkin, as well as his militant ideas about the creating a national school of drama.[27] Curiosul featured the first ever Romanian introduction to William Shakespeare, done by Bolliac himself (he used Le Tourneur and Guizot as his sources).[28] In its political pages, Curiosul pushed a liberal program, which caused the state censors to step in. Bolliac was denied on his attempt to publish an abolitionist piece in one of the magazine's four issues, but managed to establish links with Romanian intellectuals living outside Wallachia—Constantin Negruzzi in Moldavia, George Bariț and Timotei Cipariu in Austrian Transylvania.[29] Sources disagree on whether the journal was ultimately banned by the Regulamentul regime[30] or simply brought down by financial difficulties.[31] Bolliac returned to translating in 1837, when he finished a Romanian rendition of Victor Hugo's Angelo.[32] At the time, he had parted ways with Heliade and the Philharmonic, after a conflict between himself, as the dramaturge, and C. Aristia, as the producer.[33]

Bolliac maintained a close relationship with Câmpineanu, who represented liberal-minded boyars in the Wallachian Ordinary Assembly, and in 1836 drafted his friend's memorandum against the Regulamentul regime.[34] Bolliac later claimed to have been arrested during the clampdown, but this remains doubtful[35] (though he is known to have demanded that he be imprisoned alongside his friend).[36] Late in life, he outed the Câmpineanu group, himself included, as a Masonic organization targeting Tsarist autocracy, and Câmpineanu as a "Grand Master".[37] As reported by the French observer Jean Alexandre Vaillant, Bolliac was told by Prince Alexandru that he could only return to publishing if he made his newspaper entirely apolitical.[38] Instead, Bolliac tested such bans by circulating various other papers and poems which progressive messages. In 1839, his house was unexpectedly searched by Captain Costache, who was acting on orders from Aga Manolache Florescu, and who reportedly confiscated all of the Bolliac papers.[16] He was apparently spared further retribution. Employed by the Wallachian State Secretariat as a 3rd-degree functionary,[39] he worked with August Ruof, who featured samples of his social poetry in the newspaper Pământeanul.[40]

Prisoner and prosecutor

Bolliac was eventually implicated in Mitică Filipescu's "insurrection against the Russian protector",[41] which possibly aimed at creating a Wallachian republic.[12] Also dragged into the affair, Vaillant protested that Bolliac and Filipescu, as well as all other conspirators, "all of them gentlemen or sons of gentlemen", were "abandoned" by Prince Alexandru to the Russians' retribution.[42] Bolliac suspected that he and the others had been betrayed by Heliade, finding clues of this in Heliade's fable, Căderea dracilor ("Fall of the Demons").[43] Arrested at Giurgiu, he was taken to the Aga's manor in Bucharest; in the prison annex, he scratched satirical rhymes into the walls.[44] He reported having spent some nine months in jail,[45] before being indicted for conspiracy in March 1841. Following pleas made on his behalf by Great Ban Mihalache, he was only found guilty of instigation during the final tribunal session, on 9 April.[46] Bolliac himself had expressed remorse, informing the monarch that he was no longer obeying the "demon of literature".[5] He was deported internally at Poiana Mărului Monastery, which made him "luckier" than the other captives: while they were directly exposed to respiratory disease, he could breathe "clean mountain air", and only had to put up with a Russian Orthodox monk reading him from the prayers of Saint Basil.[47] He was probably released around June of the same year.[48] In 1842, alongside brothers Ștefan and Nicolae Golescu, he traveled about the Southern Carpathians.[49]

Upon taking the Wallachian throne in late 1842, Gheorghe Bibescu revived Bolliac's career, making him a public prosecutor.[50] The new ruler also gave an enthusiastic reception to one of Bolliac's poems, which espoused a generic nationalist-progressive goal (namely, the inauguration of a Wallachian commercial fleet).[51] Despite being promoted to Praporcic and Serdar,[52] Bolliac engaged on the conspiratorial side of Wallachian liberalism, joining the committee of a secret society known as Frăția ("Brotherhood"). This activity required him to reconcile with Heliade, their understanding brokered by a young radical, Nicolae Bălcescu.[53] The latter also helped Bolliac gain traction in Moldavia, sending one of his poems to be published in Mihail Kogălniceanu's Propășirea.[54] In 1843, Bolliac also appeared at a literary salon hosted by Anica Manu, wife of Aga Ioan Manu. His presence there unnerved the Russian consul Peter I. Rickman—who believed that the Manus were cultivating a Wallachian answer to the Carbonari. Aga Manu assured him that Bolliac and the others were only kept close so as to never pose a challenge.[16][55] In March of the following year, Frăția created itself a front organization, called "Literary Association". Bolliac was a member, but Heliade was excluded, being singled out as uncollegial.[56]

Bolliac tested Bibescu's toleration by engaging with Heliade in a campaign for press freedoms; his poetry volume, also published in 1843, was heavily redacted by state censorship.[57] It appeared with lengthy dedications to his two boyaress benefactors, Catinca Ghica (mother of the more famous Dora d'Istria) and Marițica Văcărescu.[58] He continued to associate with the boyar elite, visiting Cleopatra Ghica-Trubestakaya and other members of the Ghica family at their estates on the Prahova Valley; vacationing for lengthy periods in Băicoi and Câmpina, he turned for a while to writing mainly love poems that appealed to female sensibilities.[59] It was possibly around that time that Bolliac visited the salt mines in Telega, which were staffed by imprisoned criminals or political suspects, and which inspired him openly support prison reform.[60] He also took baths in Transylvania, at Vâlcele (Előpatak), where he met and befriended the local poet Andrei Mureșanu.[61] He and Bălcescu returned to the Bucegi Mountains in 1845, climbing up the Caraiman Peak.[62]

As a traveler, Bolliac began a research into Romanian folklore: before 1847, he discovered, and arranged for print, a version of the Meșterul Manole story, which later came to be seen as a Romanian foundational myth.[63] He was thus the first author to seek inspiration in that legend, ahead of N. D. Popescu-Popnedea.[64] Also then, Bolliac discovered his passion for archeology and numismatics. His education in these fields was handled by an older aficionado, General Nicolae Mavros.[65] Together with his stepbrothers, and with friends such as Dimitrie Bolintineanu and August Treboniu Laurian, Bolliac began exploratory digs along the Danube, and in the hilly area between the Olt and the Prahova.[66] During his traversing of Muscel County in 1845, he stopped at Jidava, recording its original name of Jidova (modified in later works by Constantin D. Aricescu, who artificially incorporated a Dacian particle).[67] Additionally, Bolliac's team answered calls made by Kogălniceanu, who wanted to establish an inventory and collection of Danube-area inscriptions.[68] The effort was weakened when Bolliac and Laurian (described in some context as the actual leader of the expedition)[69] clashed with each other in a publicized polemic.[70] The various findings were detailed as a travelogue, first serialized by Curierul Românesc.[71] In July 1845, Bolliac and his teammates uncovered traces of a settlement outside Zimnicea, which they originally regarded as a Roman outpost, but later proved itself as one of the most important sites attesting to the material culture of the Getae.[72] Though theirs was long regarded as the first archeological expedition in Romania, it was in fact predated by Gheorghe Săulescu's work in Moldavia, whose results had been communicated in 1835.[73]

Bolliac's introduction to utopian socialism took place in or around 1840, when he revealed himself as a follower of Henri de Saint-Simon.[12] Writing for Vestitorul Românesc newspaper in 1844, Bolliac took up social criticism in favor of "fashion"—embedded within was his praise of capitalism as a social equalizer, itself a tenet of Saint-Simonism.[74] He also wrote an epic poem about Tudor Vladimirescu, leader of an ill-fated social revolution in 1821, but did not publish it until 1857 (having by then re-written it in French).[75] His changing political views were expressed in Bariț's Transylvanian journal, Foaie pentru Minte, Inimă și Literatură. In 1844, it featured his praise of the Moldavian Prince, Mihail Sturdza, who had opted to manumit the Romanies owned by the local metropolis. He urged other Romanians to follow Sturdza's example, assuring them that they would be recognized through the ages as "apostles of the heavenly mission, of brotherhood and of liberty."[76]

As other texts of this series show, Bolliac was turning toward a post-utopian revolutionary socialism, which viewed class conflict as a historical reality.[77] His position became extreme following his readings from Louis Blanc and Joseph Proudhon, veering into atheism and communism—he was at times explicit in his calls to abolish religion, family, and private property.[78] His agenda came to include gender equality, and he is therefore described by critic Lidia Bote as the "first Romanian feminist".[79] His positioning was at odds with the moderate politics favored by Laurian, Bariț, and other Transylvanians. Writing for Curierul Românesc in 1846, Bolliac stated his belief that "Austrian Romanians" had been enslaved by their "system of government", whereas Wallachians were generally more freedom-focused.[80]

Revolution and aftermath

Though known to his peers as a republican,[81] Bolliac was otherwise still close to Bibescu, and, also in 1845, wrote the lyrics to a cantata honoring his liege.[82] This piece, or another one also dedicated to Bibescu, was sung at Saint Sava gatherings, under headmaster Petrache Poenaru—the latter was honored with his own musical piece, itself held to have been written by Bolliac.[83] In November 1846,[84] the young author married Aristia Izvoranca, daughter of Paharnic Alecu Izvoranu (died 1857),[85] with Mavros officiating as their godfather. She brought her ownership of an estate in Glina, as well as 1,000 Thaler; a daughter was born to the couple as their only child, but she died in childhood or infancy.[86] For unknown reasons, the Bolliacs did not reside on any of the Pereț properties, but had moved into Cezar's native neighborhood, at Boteanului.[87]

Bolliac emerged as a prominent figure during the Wallachian revolution of 1848: in May, he joined a revolutionary committee that also comprised Heliade, Bălcescu, Ion Brătianu, C. A. Rosetti, the Golescu brothers, and various others.[88] He was personally tasked with agitating among the Bucharest tanners, those living in the outer quarters, and the youth.[89] In June, Bibescu, having fought back against the crowds, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt. The shooters included Bolliac's stepbrother, Grigore Peretz.[90] Bibescu fled the country, and a provisional government took over. Bolliac announced these events from the princely palace balcony, where he also read from a new constitution.[91]

Bolliac and Bălcescu were secretaries of the new executive body from 21 June. On 24 June, government managed to defeat a reactionary uprising by Ioan Odobescu, with Bolliac leading the counter-charge.[12] Immediately after, he was appointed governor, or Vornic, of Bucharest.[92] From that position, he exercised direct control over the guilds, which were the revolution's main backers.[93] He also presided upon the City Council, alongside the Jewish financiers Solomon I. Halfon and Manoah Hillel.[94] On 3 August, he was inducted by a commission on school reform, under minister Heliade.[95] Three days later, he joined a panel that prepared elections for a Wallachian constitutional assembly.[96]

Bolliac soon formed and presided upon his own political party, called either Clubul Regenerației ("Regenerative Club")[97] or Clubul Român ("Romanian Club").[98] He engaged in revolutionary propaganda as editor of Popolul Suveran newspaper,[12][99] which hosted his own political poetry.[100] Moreover, Bolliac spoke to crowds of Bucharesters gathered at "Liberty Field". It was here that, on 19 August, he proposed a national pantheon of statues, with depictions of Vladimirescu, Michael the Brave, and Gheorghe Lazăr.[101] In July,[102] the provisional government had also assigned him to a commission of abolitionists, which was supposed to manumit the Romanies. He was a public face of this effort, alongside priest Iosafat Snagoveanu—both of them were unusually "swarthy", leading some of the Romanies to regard them as "our people."[103] The was controversial: Bolliac collected sums which the Romanies paid in exchange for the freedom, but apparently never returned the funds. As noted by Bolliac's conservative opponent, Grigore Lăcusteanu: "This money has been taken and then wasted by one of the vagabonds, namely Cezar Bolliac."[104] Historian George Potra reports that Bolliac was only marginally involved with the commission. Busy as a Vornic, he only signed Romani-related papers for a few days after his appointment.[105]

Upon surviving an assassination attempt by "reactionary aristocrats" on 24 August, Bolliac grew more bitter, and demanded that the revolutionary conquests be defended by military force.[106] On 6 September, he and C. Aristia spoke at a rally during which copies of Regulamentul Organic were publicly burned.[107] He backtracked in at least one article for Popolul Suveran, asking the Imperial Russian Army, already present in Moldavia, not to invade Bucharest.[5] In September 1848, an Ottoman intervention ended the Wallachian revolutionary experiment, and its enablers were forced out of the country, as hostages of the Sublime Porte; Fuad Pasha personally handled the clampdown, mandating that Bolliac and the others be moved to a prison camp in Cotroceni,[108] then sailed up the Danube under escort. As part of a transport ultimately bound for Bosnia Eyalet,[109] they were taken in harsh conditions to Svishtov, then to Vidin, and finally to Fetislam.[110] On 15 September, they were at Orschowa, on Austria's Banat Military Frontier.[111]

In Transylvania and Hungary

According to popular legend, revolutionary sympathizers Maria Rosetti and Constantin Daniel Rosenthal, who had followed the ship, was able to drug the Ottoman guards in charge of the convoy. This allowed Maria's husband, C. A. Rosetti, to escape from the convoy in wagons, alongside several other inmates: Bolliac, N. Bălcescu, Bolintineanu, Brătianu, and the Golescus.[112] Another account suggests that they were allowed to leave outside the Iron Gates, which they crossed by foot, with some switching over to a ship of the Austrian Lloyd.[113] Bolliac entered Transylvania, now disputed between various revolutionary movements; he settled among the Romanian-speaking community of Brașov.[114] His wife remained in Wallachia, where she was arrested and humiliated by the post-revolutionary regime.[115] She eventually joined Cezar in his place of exile, where he had launched the newspaper Espatriatul ("The Expatriate"), with Snagoveanu and Costache Bălcescu as co-editors.[116] Its first issue, appearing on 25 March, proclaimed that all revolutionaries had one single cause, and that the social war was opposing "peoples to dynasties".[117]

Among the Wallachian revolutionary exiles (or căuzași), Bolliac was regarded as a dangerous extremist—a reputation which he shared with Nicolae Bălcescu and Ion Ionescu de la Brad.[118] He and Bălcescu were also rendered eccentric by their take on Hungarian–Romanian relations, which had been strained by a latent conflict over Transylvania. Whereas most Wallachian liberals had come to fear and resent the Hungarian revolution, which had repressed Romanian activities in Transylvania, Bălcescu and Bolliac still believed that they could mediate a truce between the two peoples-in-arms,[119] followed by a "united front" against the reactionaries.[12] The newly established Hungarian State, represented locally by Józef Bem, was pleased with the editorial line at Espatriatul, and especially with its proposing a truce between Bem and the Romanian Transylvanian guerilla commander, Avram Iancu. The newspaper was therefore allowed to remain in print, unlike Bariț's Foaie.[120]

For his part, Bolliac hoped that Bem would cross into Wallachia to rekindle the revolution there, and composed a march in his honor—also indicating that Bem was his favorite among the would-be rulers of a Romanian state.[121] The Romanian Eastern Catholic priest Ioan Munteanu, who was offered a job at Espatriatul, would not accept it; despite his confessed respect for Bolliac, he regarded the enterprise as a tool for Magyarization.[122] In his pseudonymous correspondence of that period, N. Bălcescu mocked his colleague for being too subservient to "the Magyars, with whom he has formed some pact". According to Bălcescu, Bolliac had always had trouble selling off his "bad and numerous works", but had found himself assisted by Bem, since Romanian communities were forced, under pain of death, to buy Espatriatul subscriptions.[123] Overall, the publication had a "minuscule" readership.[5]

On 14 June, just ahead of a Russian invasion in support of Austrian interests, Bolliac fled to the Hungarian capital of Pest. Once there, he relaunched Espatriatul as Amicul Poporului ("Friend of the People"), now targeting Romanians in Hungary.[124] Bolliac was the radicals' emissary in Pest—on 22 June, he was joined there by Bălcescu, discussing an inter-communal detente with Hungary's leader, Lajos Kossuth.[125] Bălcescu was held up by Kázmér Batthyány, who was Kossuth's Foreign Minister, and who discreetly opposed the project. As a result, Bolliac was "coached" by Bălcescu, and had to do most of the work.[126] Together, the two Wallachians persuaded their host to move away from his advocacy of a unitary state, and closer to ethnic federalism.[127] In July, Bolliac relocated to Debrecen, where he obtained Bem's support for the enrollment of Wallachians in the Hungarian Defense Army.[128] On 14 July 1849, the "Act of Pacification between Magyars and Romanians" was signed at Szeged, with Bolliac and Bălcescu listed as representing the Romanians in general.[3][127][129] A discovery of the original text in 1988 shows that it was not in fact signed by Bolliac, who was not yet in that city. His signature had been forged by Bălcescu.[130]

Immediately after, the two Wallachians, granted spending money and safe passage by Kossuth,[131] left for Cluj, then for Câmpeni, where they met with Iancu. The latter agreed to a ceasefire, but not to a full peace—being aware that Kossuth did not stand a chance against the Russians and the Austrians.[132] Upon reaching Szeged, Bolliac was asked by Kossuth to contact Omar Pasha, who was leading the Ottoman forces occupying Wallachia, and obtain his neutrality in the Hungarian–Russian war. This mission, which required his return to Orschowa, was funded with assets confiscated from the pro-Austrian landowner Jenő Zichy.[133] Later historiography informs that this conditional sponsorship was handed to him as a set of diamond buttons. Bolliac picked the items up at Radna,[134] and apparently used them in covering his own expenses.[1][135][136] All of Hungary's self-preservation efforts were nullified on 13 August, when the Hungarians surrendered, leaving Transylvania to resume its existence as an Austrian province. By his own account, Bolliac made frantic efforts to rejoin Bem, but was cut off by the Russian advances, and eventually sought refuge in Serbia.[137]

Records consulted by the Hungarian scholar István Hajnal contrarily show that Bolliac was in Orschowa with Kossuth, who had asked for the diamonds to be returned, in order to finance his own efforts abroad. The encounter was tense: "Bolliac [gave] Kossuth a gold spur of lesser value, but he said that the rest, the expensive diamonds, had been lost."[138] According to one account, it was Bolliac, rather than Kossuth, who buried the Holy Crown of Hungary, for safekeeping, somewhere outside Orschowa (he was subsequently "accused of having broken off the crown's precious stones and using them for his own purposes").[139] He met Bălcescu one final time, in Karansebesch,[140] and was asked by the latter to supervise development in Wallachia from across the border, in Ottoman Bulgaria.[141] Taking over as Prince of Wallachia, Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei noted with satisfaction that Bolliac had only passed through Ruschuk, where just "twelve of the most insignificant [rebels]" still resided in January 1850.[142]

In Istanbul and Paris

Bolliac had traveled farther south in the Ottoman Empire, moving between Rumelihisarı and Bursa, and being called up for a formal inquiry at Istanbul (where his wife, who had been stranded in Transylvania, finally joined him on 24 December 1849).[143] He reunited with a growing community of Wallachian exiles, giving them news about Bălcescu's involvement in Transylvanian affairs.[144] While walking about the Grand Bazaar, he discovered a manuscript copy of Nikolai Spathari's Travels, which he purchased (and much later donated to the National Library of Romania).[145] Bolliac was twice arrested by the Ottoman authorities, who were acting on Bem's complaint, namely that he had never returned the diamonds.[146] The Zichy family also issued complaints against him; he was allegedly released only because he promised to pay off the debt, and because Âli Pasha vouched for him.[147]

In tandem, the Austrian military tribunal in Hermannstadt began an investigation into Bolliac's "intimate rapport with the Hungarian insurgents", and had caught news, from one informant in Râmnicu Vâlcea, that he had reached Istanbul.[148] Upon his release, Bolliac was living with other Wallachian exiles, including Ion Ghica, in supervised conditions at Boyacıköy. He reportedly declared himself a victim of heat stroke, claiming that it had nearly killed him, in order to move with his wife to Pera.[149] In January 1850, he met one of Kossuth's friends, Major Boekh, at Bebek, asking him and the other emigrants to persuade Bem not to seek his prosecution in the diamonds affair.[150] Around that time, he went to Shumen, where Kossuth was living under imposed domicile. As noted by Hajnal, he now supported the Hungarian project for a Danubian Confederation, and, against Ghica's objections, also convinced Bălcescu of its usefulness.[151]

During early August, Bolliac was observed by Ghica making a "great fuss" about the possibility that the Ottomans could back an anti-Russian revolutionary coup in Wallachia. Ghica doubted his colleague's enthusiasm in his own letters to Bălcescu, noting in particular that projects to form a Wallachian revolutionary army, under Gheorghe Magheru or Christian Tell, were especially naive or dangerous; according to Ghica, Bolliac was also suspicious for having mysteriously shed his outstanding poverty, having paid off all of his and his wife's debts.[152] By mid-1850, Prince Știrbei and his ministers had volunteered to collaborate with the Austrian Empire in preventing the more "incorrigible" radicals, Bolliac included, from ever returning to Wallachia.[153] Continuously threatened with prosecution,[154] Bolliac decided to flee the Ottoman realm. As recounted by Ghica, he had already broke his interdiction by entering Pera, whence he sailed out clandestinely using the false name "Timoleon Paleologu"—while still claiming that he was aiming for Wallachia, in order to reignite the revolution there.[155] In fact, he entered the Kingdom of Greece, reaching Athens by 20 August;[156] from there, he sent money to his wife, who had tried to leave Ottoman territory on her own, without settling other debts she had incurred at Pera. As Ghica notes, the Bolliacs left behind them the "worst reputation", harming that of the expatriates as a whole.[157] Cezar was eventually granted a British passport (as "Paleologu"), entering the Crown Colony of Malta on 21 September.[158] He sailed for Republican France, arriving at Paris during mid-October 1850.[159]

From Paris, Bolliac embraced the new agenda of revolutionary factions from Wallachia and Moldavia, namely the unification of the two principalities. He saw this as a preliminary step toward the creation of an independent Greater Romanian state, stretching into Transylvania. In one of his period texts, he argued that all it took was for some hundreds of Wallachians to instigate a guerrilla war in Austrian-held territories; he also theorized that doing so would ultimately also cause a revolution in all Romanian territories, leading for Romania's emergence as an egalitarian polity.[160] In February 1851, he joined a quasi-party of the Romanian emigrants, called Junimea Română ("Romanian Youth") and modeled on Young Italy.[161] He had planned to launch a new edition of Popolul Suveran, as one of the ambitious literary projects that were regarded with some amusement by Bălcescu.[5] Around then, Bolliac joined the left-liberal circle formed by C. A. Rosetti, and contributed to Rosetti's Paris-based magazine, Republica Română ("The Romanian Republic"). It was here that he published his in-depth critique of Regulamentul as a remnant of feudalism.[162] The Bolliacs and that branch of the Rosetti family became very close. As recounted by Rosetti's son Vintilă, Aristia "looked after all the exiles when they fell ill", while Cezar, "the great gastronome", cooked for them; in 1852, as the Rosetti children got measles, they took one of the healthy girls into their own home—she was looked after by Cezar, when his wife had also contracted the disease.[108]

In 1853, Rosetti Sr published Bolliac's historicist essay, Unitatea României ("Romania's Unity"), which presented a corpus of evidence for the nationalist claim.[163] Bolliac mounted a campaign of "intense propaganda" for this unionist cause, with articles as well as poems,[164] and sent pleas to various international leaders, beginning with Louis Napoleon in 1852.[165] The latter agreed to receive him for a three-hour meeting.[79] In Wallachia, his non-political poetry was only gaining in popularity, after being set to music by Anton Pann.[166] However, Ghica's dislike for Bolliac was by then mirrored by various members of the revolutionary exile, including the Golescu family as a whole: in June 1853, Alexandru Golescu-Albu told his cousins that they should never have cultivated Bolliac, a "gangrene and a shame".[167] In 1856, as unionism was intensifying, Bolliac offered more arguments for the cause with another essay, published by Stéoa Dunărei, tracing cultural unity back to the Dacians. In 1857, he issued a "topography" of Romania, intended as the first of an eight-volume encyclopedic study.[168] Here and in other brochures, he experimented as a heraldist, combining the Wallachian, Moldavian and Transylvanian arms into a pan-Romanian symbol. He changed the old tinctures of each field to match the Romanian tricolor.[169]

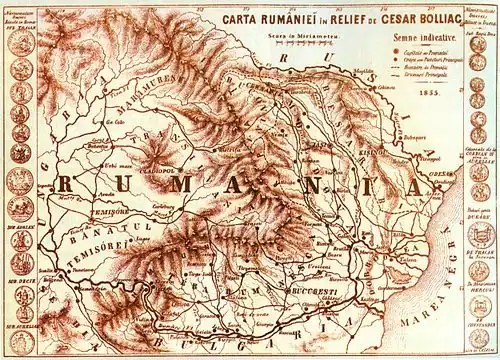

Bolliac presented his historical essays, including a topographic map that was said to be of his own design, to European chancelleries, raising awareness about "Romania", or "Moldo-Wallachia", as distinct from "Turkey-in-Europe".[170] The geographical space he defined as a homeland held the Tisza valley, the Banat to Pančevo, as well as all of Bessarabia and some of Podolia.[171] The map was shown to have been almost entirely copied from one done by Jean Léon Sanis of the Collège Sainte-Barbe, who took Bolliac to court and won 300 French francs in damages.[172] In reviewing his own work, Bolliac declared his satisfaction at having ensured that "my motherland will become known to the world of science".[173] However, as historian Nicolae Iorga argues, he presented a challenge to later scholarship: since "nobody [in Europe] had any precise ideas about Romania", he was free to add his own confabulations.[174]

In the 1859 union

The exiled Bolliac was also becoming an influence on a new generation of nationalists who were studying in Paris, including the Wallachian Alexandru Odobescu[175] and the Moldavian V. A. Urechia. The latter was attracted into a subversive network, smuggling revolutionary literature back into the two principalities. As he reported decades later, he could take select manuscripts by all of the căuzași "excepting Cezar Bolliac", since the latter was widely disliked by the community of exiles.[176] He was still viewed as a suspect in Bucharest, though Prince Știrbei did not accept Austrian demands to have Bolliac's assets seized, objecting that there had yet been no due process.[108] In February 1855, the same Știrbei had issued a secret list of căuzași who were barred from ever entering Wallachia; Bolliac was mentioned by name, as were his stepbrothers.[177] In 1857, Bolliac began publishing his own left-nationalist paper, Buciumul (named after a folk musical instrument), putting out its first series from Paris.[178] In this incarnation, it had a three-pronged agenda of unification, increased autonomy, and rule by a "foreign prince".[179]

Bolliac finally returned to his homeland in July 1857,[180] and was as such among the last expatriates to be allowed reentry.[181] This was after the Crimean War had ended the Regulamentul, placing the two countries under an international mandate (though still as Ottoman subjects). Like the other returnees, he had promised not to engage in conspiratorial activity against the Porte.[182] He immediately joined Rosetti's new literary and political club, set up in Bucharest; its junior members included N. T. Orășanu.[183] In the legislative elections in 1857, which sent delegates to the ad-hoc Divan, he positioned himself on the left, seeing the unionist movement in Wallachia as infiltrated by "reactionaries".[184] The catch-all unionist camp, or "National Party", considered making him its candidate for the landowners' college in Ilfov County, but ended up preferring a less divisive public figure. In his effort to persuade potential backers, Bolliac had stated his respect for property, family and religion; his adversaries, meanwhile, tried to prevent him from even qualifying as an elector, by bringing up the Zichy affair.[185]

The resulting unionist-majority Divan awarded Bolliac recognition, making him editor of its newspaper of record.[186] In tandem, he was co-editor of the leading nationalist magazine, România, contributed to Rosetti's Românul, and published a selection of his own poetry—as well as Mozaicul social ("The Social Mosaic"), being his definitive essay on stratification under Regulamentul Organic.[187] In an 1858 text called Despre daci ("On the Dacians"), he stated his belief that the origin of the Romanians was mostly tied to Dacia rather than to the Roman Empire. He also told of Dacians as a powerful and literate race, voicing his belief that a Dacian alphabet would eventually be discovered.[188] He argued therein that the Romanian mission in archeology was to provide "exact ideas on who the Dacians were."[189] Like the younger Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, Bolliac strongly believed that Dacian religion was quasi-Christian, thus accounting for the solidification of Christianity in Romania.[190]

During 1858, Wallachia was ruled by a triumvirate of conservative regents, or Caimacami. Bolliac, who had resumed his archeological digs along the Danube (at Rușii, Turnu Măgurele, and possibly also Zimnicea),[191] was singled out for soft persecution, and prevented from continuing with his work.[192] Âli Pasha, who had reemerged as Grand Vizier, asked the Caimacami to also seize all of Bolliac's assets, and have them assigned to the Austrians.[108] The regime was more committed to stripping Bolliac and Rosetti of their voting rights, under various pretexts, though both were reinstated by the electoral tribunal.[193] Rosetti and Românul endorsed Bolliac when he sought to be voted in as a member of the Elective Assembly, tasked with selecting a new prince; he presented himself in "13 vacant [electoral] colleges".[194] In September, the two radical journalists found common ground with Heliade, Vasile Boerescu and Petre Ispirescu, establishing the Association of Printers, which functioned as a trade union.[195]

In that context, the Nationals grouped all their forces around Alexandru Ioan Cuza, a Moldavian colonel who had won the princely election in that country. Bolliac was reportedly the one who noted that Cuza could qualify for running in Wallachia during January 1859, earning support from the other Nationals, beginning with Barbu Vlădoianu.[196] While still not a registered elector, he managed to prevent Heliade (now perceived by the Nationals as an Ottomanist enemy) from being sent to the Divan. Heliade now openly resented his former disciple, mocking him as Sarsailă ("Old Nick").[197] He depicted his former associate as an eternal demagogue with mental issues, additionally suggesting that Sarsailă was a foreign agent.[198] The rise of a unionist majority resulted in Cuza being proclaimed as Domnitor of the United Principalities—known colloquially, and later officially, as "Romania". Bolliac remained active on the political scene: in February 1859, he declared himself elated not just Cuza had been elected, but also that his arrival had prevented rule by a "foreign prince". Unlike Bolliac, many on the unionist right, including Cuza himself, still regarded the selection of a foreign aristocrat as optimal for the national interest.[199]

For and against Cuza

In March 1859, Bolliac was putting out a newspaper (known in French sources as Le Soldat). His former friend Ștefan Golescu, who had read a few samples, noted that they "reek[ed] of communism", and that Bolliac had "lost his mind" to agitate for such causes during a delicate period.[200] As the Nationals divided themselves into "White" and "Red" groups, respectively standing for conservatism and liberalism, Bolliac spoke out in favor of the latter, and in particular against ongoing limitations on political freedom. He wrote in support of press freedoms, demanded freedom of assembly, and argued that landowners could not be prevented from freeing sharecroppers of their remaining bonds—since doing so was a function of property rights.[201] He was unusually vocal in defending the latter set of rights, viewing property as the "basis and sustenance of families".[202] Bolliac regarded "moderate" as a term of insult, seeing it as a euphemism for allies of the reactionary right.[203] He also continued to signal his own relative moderation, and, in his 1859 articles for Românul, attacked socialism in all its forms, declaring that the forty-eighters had had no vision other than patriotism.[204] One such piece shows that he was only familiarized with utopian socialism and mutualism (both of which he now rejected), having no awareness of newer currents such as Marxism.[205]

Overall, Bolliac argued that the old political class had been compromised by its opposition to the union, leaving it to either embrace reform or be purged from political offices.[5][206] In 1860, Bolliac himself began serving as a magistrate for Bucharest's appellate court.[207] He published an influential album of Romanian archeology, historical numismatics, and heraldry, and involved himself in controversies over local symbols (in particular the arms of Iași city).[208] At this stage, Bolliac grew highly dismissive of an amateur historian, Dimitrie Papazoglu, with whom he competed for the public's affection.[209] He also maintained a focus on discussing the creation of a Romanian Army, and in November 1860 called for it to be created within a "new [military] system", as a Landwehr. He then campaigned for the mass incorporation of local peasants, of trained occupational groups such as forest wardens, and of Transylvanian migrants.[210] He collaborated with Magyar Közlöny, a left-wing newspaper of the Hungarian Romanians, urging them to support the Italian unification.[211]

A widower since April 1860, Bolliac buried Aristia at a designated family plot in Bellu cemetery (this being one of the first attested burials in that location).[212] He then decided to sell off his the Glina estate, and had his assets tied up in investments—setting a personal example toward the creation of a Romanian capitalist class.[213] Before 1861, he repeatedly tried to get himself elected into either the Assembly of Deputies or the General Council of Bucharest, put up as a candidate by România newspaper.[214] Bolliac won a deputy seat in the parliamentary elections of 1860, but his colleagues invalidated the results before he could be sworn in.[1][108][215] This affair became a national scandal after Brătianu handed in his resignation from the cabinet, accusing Austria of having interfered to obtain Bolliac's removal.[216] During the "heated debates" on 5 June, Dimitrie Ghica, chairman of the Wallachian assembly, sided with the right-wing, supporting nullification of Bolliac's mandate; the Zichy affair, and the Austrian complaints regarding Bolliac, were again brought up against him.[1] In August, Bolliac was still protesting against his ineligibility as proclaimed by the Caimacami, and left in place by Cuza. He planned on suing the former regents, but found that there was no precedent for doing so.[108][217] He managed to get a councilor's seat (also in 1860), having won additional backing from the left, which now labeled itself "National Party".[218]

The political class as a whole was marginalizing Bolliac—objecting to his perceived radicalism, as well exposing his role in the Zichy affair.[219] In articles he penned for România, and for papers put out by Bolintineanu and I. G. Valentineanu, he now supported democratization and electoral reform, while leading a protest movement that petitioned Cuza to extend voting rights.[220] On 11 June 1861, he appeared at the "Liberty Field" during a festive anniversary of the 1848 events. While there, he committed himself to supporting universal suffrage, intending to petition Cuza regarding its enactment.[221] The document was eventually drafted by him, and signed by 400,000 citizens—being regarded by his supporters as "really a plebiscite."[222] He was still a city councilor in October 1861, when he approved of a campaign to mass poison the endemic street dogs.[223] He resigned just days after, together with all his colleagues. Theirs was a protest against D. Ghica, who, as government head of Wallachia and organizer of its "White" caucus, had denied Bucharest some forms of financing.[224] Bolliac returned as a National Party candidate in the legislative elections of late 1861.[225]

Bolliac was hotly opposed to the first Prime Minister of Romania, the conservative Barbu Catargiu. Bolintineanu and the liberal activist Eugeniu Carada both claimed that Bolliac had suggested physically liquidating Catargiu, for being an obstacle to Cuza's reformist agenda—since Catargiu was assassinated in June 1862, the remark was cited as proof of Cuza's involvement.[226] From December, Bolliac began publishing a new series of Buciumul. It was for a while roughly similar to Românul, including in its praise of Russian radicals such as Alexander Herzen.[227] The period also saw the emergence of a liberal–conservative alliance against the increasingly isolated Cuza. Bolliac himself labeled it a "monstrous coalition", and the name stuck.[5][228][229] His position was now in favor of centrism, with a total rejection of radical liberalism.[230]

The writer was also mounting Romania's first press campaign, exposing the Greek monasteries of Mount Athos and Sinai, as well as the Ecumenical Patriarchate, for owning vasts amounts of land in Romania, and calling for all such property to be nationalized and redistributed.[5][231][232] In addition to endorsing union between the Romanian polities north of the Danube, he now campaigned on behalf of the Aromanians, who were seeking cultural autonomy in the Ottoman Balkans. In the early 1860s, he met Archimandrite Averchie, sent in by the monks of Athos to negotiate on their behalf. In a private moment of nationalist effusion, Averchie informed him that: Și eu hiu armãn! ("I too am an Aromanian!").[233] Bolliac also played host in Bucharest to Dimitri Atanasescu, the Aromanian tailor and political activist, who was taught standardized Romanian by Bolliac's nephews.[234]

Establishing Trompeta

Bolliac's centrism still included the advancement of radical goals such as land reform and universal suffrage, and he saw Cuza as moving in the same direction.[235] One consular report of that time locates him among the extreme liberals, alongside Bolintineanu and Christian Tell, since he proposed redistributing boyar land among the peasants, without any compensation to the boyars themselves.[236] Bolliac endorsed the Domnitor when the latter advanced and cemented the land reform, but became extremely critical of other segments of the Cuzist agenda.[237] An article he published in Românul featured accusations against the Romanian political class, challenged over not having done much to advance the monasteries issue. Prosecutor Nicolae Moret Blaremberg read these as an act of lèse-majesté "against the person of Domnitor", taking Bolliac to court in January 1863.[231] Bolliac challenged his accuser to a duel with pistols, wounding him in the thigh; in a parallel face-off, one of his Pereț brothers struck Nicolae's brother, Constantin Blaremberg, with his sword, giving him a head wound.[238]

Bolliac ultimately served eight months in prison, beginning in February 1863.[239] Upon his return, he signed his name to a political manifesto of the Macedo-Romanian Committee, which voiced the claim that Aromanians were a branch of the Romanian people; this presented a challenge Cuza's foreign policy, which had emphasized friendship with Greece over the Aromanians' anti-Greek mobilization.[240] He was protected by Catargiu's replacement, Nicolae Kretzulescu (whom he regarded as his good friend), but suffered renewed persecution from October 1863, when Mihail Kogălniceanu formed a new cabinet. In a letter to Cuza, he complained that he had been labeled an unreliable turncoat, precisely because of his conditional support for the Domnitor (and also because Buciumul took in a state subsidy, which Bolliac now renounced).[241] In January 1864, Kogălniceanu was formally accused by Bolliac of supporting the "monstrous coalition", and was forced to issue a rebuttal.[242] Over the following months, Bolliac and Buciumul became alarmed about the new class of Jewish immigrants to Romania, rejecting their emancipation and assimilation, and debating over the issue with the Qahal.[243] Now supported by Hasdeu (who debuted as a novelist in Buciumul's feuilleton of 1864),[244] he pushed for more extensive democratic reforms, including universal suffrage; as Hasdeu notes, he managed to expose Rosetti as a hypocrite, who talked about such goals without ever backing concrete measures to achieve them.[245]

On 2 May 1864, Cuza dissolved the Assembly and began an authoritarian phase of his reign; Buciumul was somewhat critical of such moves (since the Assembly had been too "oligarchic"), and only fully complied with Cuza's guidelines after a formal warning.[246] Bolliac was still rewarded for his scholarship, serving as head of the National Archives from 7 August.[247] He used his time there to collect all documents pertaining to the monasteries issue, which were to be used in the diplomatic exchanges between Romania and the Porte (which represented Sinai and Athos in the recurring dispute). He also donated six volumes of "extremely valuable" documents from his private collection.[248] Upon the takeover of monastery land, he obtained that the Archives be moved into buildings originally owned by the monks of Mihai Vodă.[249] He launched the institution's specialized journal, Revista Arhivelor, but only managed to produce four issues, all in a folio format.[250]

Bolliac returned with a critique of the November elections, arguing that Cuza had merely "parodied" universal suffrage, and had broken his own laws in the process. On 6 December, Kogălniceanu banned Buciumul under that name.[251] The paper reemerged in March 1865 as Trompeta Carpaților ("Trumpet of the Carpathians").[252] It endured in journalistic history for occasionally using red-colored paper with golden letters,[135] cast in bronze.[5] Its financial resources were another subject of controversy: Golescu-Albu alleged that Bolliac had received backing, including 100 ducats in financial aid, from Rosetti and his circle, who had been forced to shut down Românul. The same source claims that Bolliac had never intended to honor his resulting debts, either political or material, to Rosetti.[253] In the summer of 1865, Bolliac resumed his archaeologic excursions (which now consumed a large portion of his time),[254] also donating the antiquities and coins he had collected to the newly established Romanian National Museum.[255][256] In October, he sold his printing press, and invested 134,000 lei in an all-Romanian company that ran the tobacco monopoly; reconciling with Cuza, he proposed that the regime embrace protectionism and economic nationalism.[257] Rosetti became angered with his former friend, and never again mentioned his name in print until 1881.[258] The Rosetti children were also told by their father that they were not to approach the man whom they had previously known as nenea ("uncle"). They were "taken to see him" secretly after a couple of years had passed, upon which "he kissed us and fed us candy and biscuits."[108]

The "monstrous coalition" was actively conspiring against the monarch, whom it eventually toppled with a coup on 11 February 1866. A Trompeta employee, George Dogărescu, recalled that Bolliac and a Lieutenant Gorjan tried to warn Cuza of these developments, but backed down due to threats. According Dogărescu, the writer was forced to leave for provincial safety in Severin, while his Bucharest house was vandalized by his victorious enemies.[259] In public, Bolliac now endorsed the coup; just one day after Cuza had been forced to abdicate, he published in Trompeta a piece that openly mocked him—one described by Iorga as displaying "the cheekiness [...] that one finds in the pettiest of servants, when they're out looking for a new master".[260] He presented himself in elections for a deputy seat during the general election of April 1866. His constituency of choice was the peasants' college in Vlașca, where he had backing from his Pereț relatives; he was a perennial candidate, sometimes elected, and sometimes defeated (reportedly, only when governments intervened against him).[261]

Before splitting up into competing factions, the "monstrous coalition" passed through the main goals on its agenda, including the adoption of a moderate-liberal constitution and the selection of a foreign-born Domnitor. Bolliac declared himself against the solution, "in both shape and content", and was especially opposed to Carol of Hohenzollern, who was confirmed through a plebiscite.[262] He had a personal stake in the matter, since he believed that a non-Romanian ruler would liberalize the Romanian market and allow in venture capitalists from abroad—after his tobacco company had floundered, he was trying to reinvest his money in Romanian oil.[263] He now found himself allied to Heliade and his Legalitatea circle, who regarded Carol's arrival as the imposition of a foreign yoke on Romania.[264] For his part, Bolliac returned to Cuzism, praising the exiled former ruler as a "great captain" who had crushed the "oligarchic class", while depicting Carol as a nonentity.[265] Bolliac was a member of the Assembly in 1866–1867, involved alongside Kogălniceanu on a panel that designed the coat of arms of Romania—a work that, once complete, reflected influences from his earlier designs.[266] In June 1866, he had lost his position at the Archives. Though formally dismissed by Carol's princely decree,[267] he was widely seen as a victim of a vengeful Rosetti, since the latter was then serving as Minister of Education.[268]

Antisemite and dissenter

After Carol's enthronement, Trompeta resumed its antisemitic agitation, including against measures proposed by "Red" cabinets to removed religious barriers on citizenship. In June 1866, it successfully pressured the "Reds" to withdraw backing for any such proposals, and also instigated an antisemitic riot in Bucharest.[135][269][270] This involvement was boasted by Bolliac, who now characterized Premier Brătianu as a "brother of the Jews"; he was also opposed, again, to the Românul group, which had depicted the rioters as "enemies of the motherland" (whereas to Bolliac they were "the flower of Bucharest's populace").[269] Trompeta hosted letters from Western Moldavia, which depicted that region as invaded by Jewish "vagabonds";[271] leaving Bolintineanu to manage the paper, Bolliac went on extended visits to those areas.[272] Also then, he mounted a campaign warning Russia not to intervene in the crisis, suggesting that Romanians would rise up in arms to defend the country. This stirred the curiosity of a Russian visitor, Grigory Danilevsky, who was told by one informer that Bolliac, "Kossuth's former aide-de-camp", had stolen jewels from the Holy Crown of Hungary.[273] As an expert on things Dacian, Bolliac was met with competition from Hasdeu, who held his own conferences on the subject. In September 1866, Trompeta falsely claimed that Hasdeu had described the Dacians as Slavs, and that he himself was an agent of Pan-Slavism.[274]

Ahead of the repeat elections of November 1866, Bolliac registered himself as a candidate in Bucharest's third college. He shared a "centrist" list with Heliade and I. C. Massim, declaring his support for national development—and restating his opposition străinism ("foreign-ism").[275] He was afterwards dragged into a conflict with the "White" Minister of Education, Ion Strat, who was pushing sweeping austerity reforms. In that context, he and Rosetti, alongside friends such as Urechia and Theodor Aman, established the "Society of Educating the Romanian People", which played a part in obtaining Strat's eventual ouster.[276] In 1867, while his archeological collection was being showcased at the World's Fair in Paris,[209] Bolliac fell ill with a mysterious disease, which was probably caused by his strenuous work. He accepted treatment from Bucharest's leading physicians, and ultimately managed to recover.[277] He spent the final portion of the year campaigning for another parliamentary election, allegedly by treating his would-be peasant voters in Vlașca. Both he and his competitor, Grigore Serrurie, were said to have engaged in ballot stuffing, which resulted in Vlașca having more votes than it had voters.[278] The Assembly decided to award that seat to Serrurie. Bolliac heckled the procedures, being consequently escorted out of the hall.[279] He lodged in a formal protest, which a majority of deputies agreed to review.[280]

Bolliac ran in by-elections during 1868, being reportedly faced with stiff opposition from the "lowest-ranking of the Reds".[281] Occupied with a course in numismatics, which he provided for the newly established University of Bucharest beginning in 1868,[255] he was again a national deputy following elections in March 1869. From May of that year, he was part of a parliamentary committee that was auditing the Ministry of Finance over its spending of money loaned from Sal. Oppenheim.[282] By then, he had met a formidable foe in Junimea, an alliance of largely monarchist and conservative youths who had proceeded to reassess, and often to deride, the cultural and social contribution of forty-eighters. As early as 1867, he sparred with the Junimist magazine Convorbiri Literare over social poetry, to which his adversaries preferred aestheticism and authenticity.[283] One of his replies claimed to expose Titu Maiorescu, the Junimist leader, for his hypocritical positioning—against social art, but nonetheless political.[79] In a landmark text he published during 1871, Maiorescu asserted that Bolliac and Heliade were equally mediocre as poets, while still "among the best" when it came to their prose.[284]

Those years witnessed tensions between Bolliac and Odobescu, after the former spuriously accused the latter of having sold off the Pietroasele Treasure, a Romanian national asset, to the South Kensington Museum.[285] Bolliac himself continued to receive praise as a scholar, and in June 1869, much to Ion Ghica's displeasure, replaced his deceased godfather, Mavros, as head of the Bucharest Archeological Committee.[286] In that context, he was an occasional, but influential, art critic, chronicling exhibits curated by Aman. Through the latter, he also discovered the young painter Nicolae Grigorescu, an impressionist, complaining that the works he exhibited looked "unfinished".[287] Bolliac was personally welcomed by Ponton d'Amécourt into the Société française de numismatique during November 1869.[288] He was additionally inducted by the Romanian Geographical Society and several other learned societies, while serving as a government inspector of the Romanian museums.[289] In mid-1869, he had camped out at Vădastra, having correctly identified it as a site of interest for research into the Neolithic; here and at nearby Romula, Celei and Bucovăț, he discovered additional troves of Roman currency.[290] Also then, and again in 1871–1872, Bolliac was Zimnicea, having by then grown convinced that he had uncovered the "apex of Dacian civilization in matters of ceramics".[291] It was at this stage that he dug up the ustrinum, alongside several urns with human remains, as well as an outstanding pithos (which he kept in his own collection).[292] He and Odobescu explored the Dacian site at Tinosu, after repeated failed attempts to uncover Zalmoxian sites in the Bucegi Mountains.[293] With the latter expedition, he explored the "Cave with Pots" at the source of the Ialomița, thus becoming Romania's first attested speleologist.[294]

For the remainder of his life, Bolliac struggled financially: he lost money in the oil business, and in 1870 divested, becoming instead one of the founders of an insurance company called Dacia.[295] His belief in economic nationalism, manifested primarily as economic antisemitism, was a mainstay of Trompeta's editorial line. He was incensed by renewed calls to emancipate the Jews, and sometimes encouraged outright violence against them.[296] In 1868, he also attacked Hasdeu for his "history of religious tolerance", in which Hasdeu had argued that the Romanians had traditionally been welcoming of, and all too lenient towards, the Jewish diaspora. In Bolliac's view, such claims risked demonstrating to Jews that they were an ancient presence in Romania.[297] In January 1870, he declared that the Golescu-Albu cabinet had betrayed the Romanians by "insisting that Jews remain the masters of Romanian trade, Romanian industry, and the entire Romanian state".[8] He combined the antisemitic agenda with a number of progressive goals, and theorized that the liberal bourgeoisie had betrayed the revolutionary cause of 1848.[79][298]

As deputy, Bolliac sounded alarms about the peasants' destitution, noting that they were starving in order to meet financial quotas imposed on them as compensation for the land they had received from Cuza.[299] He now shied away from proposing radical reforms in agriculture, endorsing instead systems of credit unions that would elevate some of the peasantry into a rural bourgeoisie.[300] In the new climate inaugurated by the reconciliation of Austrians and Hungarians, and the establishment of Austria-Hungary, Bolliac revised some of his earlier stances. After an incident at Tofalău, which had seen the eviction of Romanian Transylvanians from a Hungarian-owned estate, Trompeta commented on the Magyars as an "exotic" Asiatic race, which was testing the patience of its European subjects.[301] He had an extensive polemic with a Transylvanian lawyer, Alexandru Papiu Ilarian, whom he accused of being a Hungarian by birth, going as far as to suggest that his enemy's real surname was "Paponyi".[302]

Disrepute and alleged child-rape

Bolliac took the peasants' college seat at Vlașca during the election of May 1870.[303] He ran in the concurrent local elections, becoming a councilor for the plasă of Câlniștea. Other candidates protested by means of Românul, noting that one of Bolliac's half-brothers was running Vlașca as a prefect, and that Bolliac had never registered himself as a local taxpayer.[304] He was sent to the Assembly after elections in mid-1871, during the "Strousberg Affair"—a bankrupt investment into a private network of railways. Sitting in the opposition to "White" governments, he supported George D. Vernescu's motion to withdraw funding for the railways project.[305] In November 1871, Alecu D. Holban staged a congress of the liberal-minded press in Iași, hoping to generate momentum for the creation of a unified party of the left. Bolliac was among the main guests.[306] Though he sought his readers among the antisemitic middle classes, he failed to impress any section of the public, and, by 1874, his daily newspaper was effectively a weekly;[307] it was reportedly circulated in no more than 600 copies per issue.[308] It still had a niche appeal due to its scholarly content, with "page upon page of illustrations".[309] Like Buciumul, Trompeta also hosted historical documents found and preserved by its editor, including a version of Genealogia Cantacuzinilor (which Bolliac mistakenly credited to a scribe, Ștefan Logofătul), first-hand records kept by Pârvu Cantacuzino (in reference to the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774), and Nicolae Ruset's description of the Mavrokordatos family.[310]

In the 1872 legislature, Bolliac protested against the ambiguity that still existed in the official nomenclature, insisting that Romania should not have continued to accept being labelled as merely the "United Principalities".[311] He employed some of his time in the Assembly to protest the "calumnies proffered by Jews, namely that he was now their partisan." In that context, he also claimed that the leading Junimist paper, Timpul, was a voice of Jewish interests, printed in "Jewish".[312] He used his prestige and his position as deputy to demand assistance for his friend Bolintineanu, who was consumed by disease, and whom he regarded as a national poet; having reconciled with the dying Heliade, he appeared as a pallbearer at his funeral, in April 1872.[313] The "Whites" held on to power in the early 1870s, when Lascăr Catargiu was their Prime Minister, and Gheorghe Costaforu in charge of the education department. Bolliac annoyed them with his advocacy of extensive land reform, and was stripped of state funding for his archeological expeditions; he returned to Zimnicea in 1872, covering his own expenses.[314] This formed part of a larger expedition along the Danube, between Tulcea and the Iron Gates, with a stopover in the eponymous Ottoman province, at Nikopol.[315] In tandem, he joined Aman, Odobescu, Grigorescu and Constantin Stăncescu in setting up a society called "Friends of the Fine Arts".[316] By 1873, he owned to his name a large collection of paintings and drawings, which included identifiable works by artists from Albrecht Dürer to Morel-Fatio. He had inherited some of these from the Ghicas, and had bought others at auction in Transylvania; the descriptions allowed Bolliac's rivals at Poporul newspaper to speculate that most of the works were "cheap copies".[317]

According to number of records, including a February 1873 letter from C. Radovici, Bolliac had come to be regarded as a child sexual abuser, with Trompeta becoming a "laughing stock". Radovici reports on claims that Bolliac had groomed and then vaginally raped a 10-year old fatherless girl, whom he had adopted into his home.[135] Bolliac had allegedly recognized his crime, and had agreed to settle the matter with the mother; she changed her mind during Bolliac's temporary absence, and decided to file a complaint with the prosecutors. The latter, Radovici reported, were only to happy to seek Bolliac's imprisonment, since they had come to despise him.[135] The latter was also claimed by Uniunea Liberală newspaper, put out by the Free and Independent Faction. Without mentioning the girl's age, it described "the eminent plebeian" as framed by the Romanian Police, and the incident overall as "petty infamy".[318] As noted by historian Eugen Ciurtin, the scandal never resulted in prosecution, and was entirely buried by his biographers. Ciurtin corroborates the incident with a note that Bolliac had sent in January 1873 to his friend Tell, who was by then the Minister of Education. Here, the aging author pleads with Tell not to allow "me and my old age to be soiled in infamy"; Ciurtin also notes lyrics by Bolliac, which praise the physical attributes of preadolescent girls.[135]

After evading prosecution, Bolliac continued his digs with a visit to Piscul Crăsani, and also returned at Celei, where he discovered a sarcophagus.[319] He sent artifacts to be exhibited in Vienna, where some where sold off to private collectors,[139] and found himself scorned for his incorrect or erratic periodization.[320] His reputation as a founding-figure in archeology suffered massively when he was mocked by his younger friend, Odobescu. He focused on Bolliac's claim that Dacians were ritualistic users of cannabis and opium—smoking them in early versions of the "Romanian pipe". In attacking this concept, Odobescu implied that Bolliac was imaginative to the point of hallucinating, and as such the only one in the story who could be said to be smoking something.[135][321] Some fragments of this rebuttal also refer to Bolliac's "ravenous desires"—read by Ciurtin as likely allusions to Bolliac's pedophilia.[135] As scholar Ovidiu Papadima recounts, Bolliac delivered an uncharacteristically humble response to this critique, simply noting that his mistakes were those of an archeological practitioner, who did not have the time to improve on his methods (implying that Odobescu spent most of his time in secluded libraries). He also indicated that his larger goal, of rediscovering the Dacians, could excuse any excesses and errors.[322] In 2010, anthropologist Andrei Oișteanu observed that Bolliac was at least partly correct in his discussion of cannabis use among the Romanians, with "hemp", or Cannabis sativa, being recommended in traditional medicine.[323]

Ruin, disability, and death

Also in 1873, Bolliac tried was among the legislators who sponsored amendments to Catargiu's law on press freedom. While accepting the introduction of penalties for offending journalists, they tried to prevent the state from disclosing the names of unsigned or pseudonymous contributors.[324] He was reconfirmed as a deputy during the 1874 race, this time by a constituency in Bucharest.[325] He then focused on obtaining funds for the St. Nicholas Church of Șcheii Brașovului, which ran a network of Romanian schools in Austria-Hungary.[326] In October 1874, he visited the Romanian communities abroad, stopping in Budapest, Oradea, Cluj, Blaj, Sibiu, and finally Rășinari.[327] From November, he began serving with Alexandru B. Știrbei on the Assembly's Committee on Naturalization.[328]

Bolliac had additional contributions as a heraldist to Michael the Brave's monument, which was finally erected in Bucharest's University Square—namely, he designed an unusual version of the Transylvanian arms, which was recreated as a plate and attached to the pedestal.[329] He was again publicly ridiculed in Bucharest, having reportedly spent 30,000 French francs on a forgery ring—while made of solid gold, it had been fashioned by Ottoman dealers to seem like it had been issued by Severus Alexander in the 3rd century. In covering news of this embarrassment, Curierul paper additionally inquired: "Where did you get the money, Mr Boliac?"[325] His expertise was again recognized in April 1876, when Carol granted him the Bene Merenti medal, 1st Class, "for his literary and archeological contributions".[330] In June, Carol's wife, Elisabeth of Wied, took her mother Marie of Nassau, on a tour of Bucharest, which included a stop at Bolliac's "collection of antiquities".[331] By then, the writer was facing bankruptcy, resulting in his decision to sell his remaining objects, including his entire collection of contemporary paintings.[332]

Reconfirmed after elections in April 1875, exactly a year later Bolliac entered a slim parliamentary majority supporting the right-leaning Florescu cabinet.[333] He endorsed the Second Epureanu cabinet, prompting allegations that he was "paid directly by government."[334] Bolliac was also outspoken in his opposition to the National Liberal Party, which had fused together the "Red" movements, and which formed a national cabinet in July 1876. He warned that the new establishment, now encouraged by Russia, was busy fabricating pretexts for a war with the Ottoman Empire.[335] Adversaries such as the young author Ion Luca Caragiale identified and ridiculed him as a Bonapartist.[336] In his final articles for Trompeta, Bolliac endorsed "progressive conservatism" and D. Ghica against both Rosetti's "far-left" and Catargiu's "far-right". He regarded Romanian Orthodoxy as a state religion, and did not want Romania turned into a republic, while resenting Catargiu's blanket opposition to social reform.[337] He also changed his stance on the Hungarian issue, distancing himself from nationalist activists such as Sigismund Borlea, and confiding that "he desires peace between the Hungarian and Romanian people, from the bottom of his heart". However, he still supported the emancipation of local Transylvanian Romanians, arguing that the abolished principality should have been revived.[338]

On 22 January 1877,[339] Bolliac was struck by what physicians of that era called a "cerebral congestion", leading to paralysis.[340] According to historian Andrei Pippidi, this was the culmination of a neurological decline, also observed in his contemporaries Heliade and Bolintineanu, "to a large degree the victims of historical circumstances."[341] Memoirist D. Teleor likewise recounts that the scholar had entered a terminal physical decline, unusually visible to eyewitnesses when his white hair turned yellow.[342] He had to cease publication of Trompeta; no longer speak or write, he was reduced to a "larval" existence, and confined to an armchair.[343] "His journalistic disciples" purchased him a baby pram, which a servant used to push him around in.[342] Erstwhile adversaries took pity on him, and the Assembly voted to grant him an annual pension set at 400 lei.[344]

Bolliac was ignored by the general public, and allegedly mistreated. Eyewitness reports suggest that he was beaten up regularly by his handlers, while on his daily outings to Grădina Icoanei (located a short distance from his house on Rotarilor Street).[345] His condition only improved when his estranged disciple, N. A. Bassarabescu, drew attention to his plight.[346] He lived to witness the Romanian War of Independence, which severed the country's links with the Ottoman Empire. At the time, Romania was aligned with Russia in the larger Russo-Turkish War, and had the Imperial Russian Army returning on its soil. In July 1877, a "Mr Baranovsky" offered to purchase the Zimnicea artifacts from the disabled researcher, intending to present them as a gift to Emperor Alexander II. Bolliac was reportedly upset by these developments, since he wanted the Romanian state to buy these; "through signs, in those moments when he is free from pain, he reveals that he wants to be left his discoveries, and then he allows himself to be carried into the hall where he has stored [these] up".[139]

In September 1880, Bolliac's brother and estate curator, Petre Peretz, dismissed rumors that Trompeta was set to reappear.[347] Urechia recalls that, in late 1880, his disabled friend was traveling around Bucharest in a hansom cab, assisted by a "boy". He still could not speak, due to what Urechia describes as a "paralysis of the tongue", but used signs to communicate.[348] Teleor chanced upon him the following year, noting that he seemed to be hallucinating, and reliving his past as a revolutionary. He would only emerge from this state when pelted with stones by "brats and children".[342] His new and final address was at No 28 Speranției Street, which was next door to a dwelling inhabited by poet Mihai Eminescu.[349] He died there on 25 February 1881,[3][350] just months before Carol had established a Kingdom of Romania. The Assembly financed his funeral, and Rosetti contributed an epitaph—declaring that Bolliac fully deserved to be honored by his nation.[351] A service was held at Sărindar Church on 28 February, after which his body was buried at Bellu, with military honors.[352] As Popovici notes, his nationalist convictions had mattered little to the press of the day, with one obituary describing his main attribute as having been his foundational role in the Romanian Freemasonry.[353] Though he left no direct heirs, he had left the remnants of his art collection to a nephew, the zoologist and politician Ștefan Sihleanu.[354]

Literary work

Beginnings