Federalist No. 84

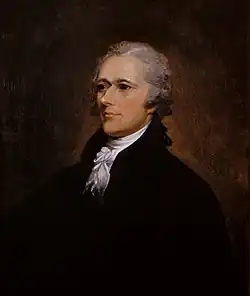

Alexander Hamilton, author of Federalist No. 84 | |

| Author | Alexander Hamilton |

|---|---|

| Original title | Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | The Independent Journal, New York Packet, The Daily Advertiser |

Publication date | July 16, 1788; July 26, 1788; August 9, 1788 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Newspaper |

| Preceded by | Federalist No. 83 |

| Followed by | Federalist No. 85 |

Federalist No. 84 is a political essay by American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, the eighty-fourth and penultimate essay in a series known as The Federalist Papers. It was published July 16, July 26, and August 9, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist Papers were published. The official title of the work is "Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered". Federalist 84 is best known for its opposition to a bill of rights, a viewpoint with which James Madison, another contributor to the The Federalist Papers, disagreed. Madison's position eventually won out in Congress, and the United States Bill of Rights was ratified on December 15, 1791.

Content

Federalist No. 84 is notable for presenting the idea that a Bill of Rights was not a necessary component of the proposed United States Constitution. The constitution, as originally written, is to specifically enumerate and protect the rights of the people. It is alleged that many Americans at the time opposed the inclusion of a bill of rights: if such a bill were created, they feared, this might later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had. Hamilton wrote:

It has been several times truly remarked, that bills of rights are in their origin, stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgments of prerogative in favor of privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. Such was Magna Carta, obtained by the Barons, sword in hand, from the king John...It is evident, therefore, that according to their primitive signification, they have no application to constitutions professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate representatives and servants. Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing, and as they retain everything, they have no need of particular reservations. "We the people of the United States, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United States of America." Here is a better recognition of popular rights than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal figure in several of our State bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government... I go further and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why for instance, should it be said, that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretense for claiming that power.

Hamilton continued in this essay on defending the notion that a bill of rights is unnecessary for the constitution when he stated, "There remains but one other view of this matter to conclude the point. The truth is, after all the declamation we have heard, that the constitution is itself in every rational sense, and to every useful purpose, A BILL OF RIGHTS. The several bills of rights, in Great-Britain, form its constitution, and conversely, the constitution of each state is its bill of rights. And the proposed constitution, if adopted, will be the bill of rights of the union."[1] Ultimately, Hamilton's argument is that a bill of rights should not be added to the constitution because the entire constitution is in itself a bill of rights. Hamilton believed that the entire document, the United States Constitution, should set limits and checks and balances on the government so that no individual's rights will be infringed upon.

Aftermath

Hamilton's argument in Federalist No. 84 was ultimately rejected. At the time, the society in the United States was divided between the Federalists, who advocated for ratification of the Constitution, and the Anti-Federalists, who were against adopting the proposed Constitution and the stronger federal government it would create.[2] A key argument put forth by the Anti-Federalists was that the current proposal for a new constitution would centralize power at the expense of states and individual liberties, as the document lacked sufficient protection for them.[3] Anti-Federalists further argued that the mere absence of provisions granting powers to the national government does not guarantee personal freedoms - they cited the Foreign Emoluments Clause in Article I, Section 9 to illustrate that the Constitution can potentially be construed to allow implied powers beyond what is explicitly stated.[4] This convinced other supporters of the Constitution, such as James Madison, that a bill of rights was necessary after all for their goal to be reached.

In an effort to help achieve ratification of the Constitution, other Federalists replied that the new Constitution would be supplemented with amendments to safeguard these rights. These amendments would be known as the United States Bill of Rights, with ten amendments being ratified in 1791.[5] The Ninth Amendment was included to address the concern that any right not expressly listed would not be recognized.[6] The Tenth Amendment reaffirmed the federal nature of the nation, stating that the states and the people retain powers that are not delegated to the federal government.[7][8]

See also

References

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander (2009). The Federalist Papers No. 84. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 435.

- ^ Banner, To the Hartford Convention (1970); Wood (2009) pp. 216–17.

- ^ Cornell, Saul (1999). The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1828. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 0807847860.

- ^ "Empire and Nation: Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (John Dickinson). Letters from the Federal Farmer (Richard Henry Lee)". Online Library of Liberty. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ "Demand for a Bill of Rights - Creating the United States | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ The Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the State of California, p. 56, California Legislature Assembly, 1989.

- ^ "Tenth Amendment". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ "Tenth Amendment". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2013.