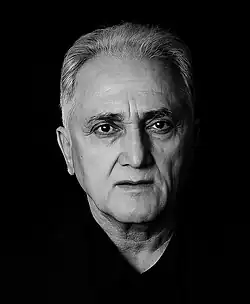

Geldy Kyarizov

Geldy Kyarizov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 January 1951 |

| Nationality | Turkmenistan |

| Occupation(s) | Horse breeder and former Minister |

| Awards | Fellow Royal Geographic Society |

| Website | www |

Geldy Kyarizov FRGS (born January 18, 1951 ~ Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic) is an internationally renowned breeder of Akhal-Teke horses and former Horse Minister for the Government of Turkmenistan (Government Association Turkmen Atlary).[1][2]

In 2002, Kyarizov was arrested by the adminstration of Saparmurat Niyazov on charges including abuse of office and negligence; a trial recognised by the international community as groundless and politically motivated.[3] Kyarizov was sentenced to six years imprisonment. Released in 2007, Kyarizov left Turkmenistan in 2015 and now resides in exile, in Prague, Czech Republic. [4][5][6]

In 2024, after years of legal battles with Turkmenistan, the United Nations Human Rights Committee issued a landmark decision in July 2024, recognising the severe violations of his rights by the Turkmenistan state.[7][8][9][10]

Biography

A longtime champion of the Akhal-Teke, Kyarizov was instrumental in reviving their fortunes after the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union and Turkmenistan's independence. Recognised for his role, then Turkmenistan President Saparmurat Niyazov, invited Kyarizov to join his government as Horse Minister (1997-2002); subsequently transformed into the Turkmen Atlary State Agency. [11][4]

Tasked with establishing an Akhal-Teke studbook using DNA analysis, Kyarizov discovered that Thoroughbred blood had been introduced into the Akhal-Teke breed, particularly for racing purposes. Kyarizov's decision to make this information public was seen as a threat to the horse-breeding establishment, which profited from the crossbreeding and led to his falling out of favour with the Niyazov government. [12][13]

In January 2002, Kyarizov was arrested. Sentenced to six years imprisonment in April 2002, in August 2006, Kyarizov was transferred to a strict regime prison. Kyarizov’s complaints concerning his imprisonment and unlawful transfer were not answered. The prison director told Kyarizov that he had no right to complain, no name and no last name, and from that point, he was known as “No. 3”. Kyarizov was released in 2007 by Niyazov’s successor Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow.[11][4][14]

Following his release, Kyarizov and his family members were under constant surveillance, his phone was tapped and his correspondence was censored. Kyarizov’s properties were confiscated and his horses taken to the presidential stud farm. Barred from leaving Turkmenistan[15] and shut out of the horse-breeding community, Kyarizov has spent the following years battling the Turkmen state for restitution.[11][4][16]

Kyarizov remained in very poor health after his release and needed urgent specialist care, but was prohibited from leaving the country. Finally granted permission to travel on September 14, 2015, his daughter Sofia and sister-in-law were denied permission to leave. Due to international pressure, the authorities relented six days later and on September 20, 2015, his daughter and sister-in-law joined their family in Moscow.[17][18]

Kyarizov and his family moved to the Russian Federation in 2015 and Czech Republic in April 2016, where they were granted refugee status.[8]

On July 9, 2024, the United Nations Human Rights Committee issued their decision re- 'Geldy Kyarizov vs the State of Turkmenistan' (CCPR/C/141/D/3097/2018). A complaint was submitted in response to egregious violations of Kyarizov's human rights, including unlawful detention, torture, and the confiscation of his property. After a thorough examination the Committee concluded that Turkmenistan is obligated to fully compensate Kyarizov. Kyarizov was awarded $7,000,000,000 USD. Turkmenistan have yet to make restitution.[10]

Ashgabat to Moscow

In 1988, Kyarizov rode an Akhal-Teke from Ashgabat to Moscow, a distance of over 4,000 kilometers (including 370 km of the arid Karakum desert) in two months, 24 days less than the previous record, set in 1935. In both circumstances, the aim was to alert the Soviet authorities to the breed’s decline and demonstrate its exceptional endurance.[4][19][12][20]

Yanardag

Yanardag (Turkmen: Ýanardag/Янардаг "Fiery Mountain") is an Akhal-Teke stallion foaled at Kyarizov’s stud farm in 1991, the year of Turkmenistan's independence from the Soviet Union. Yanardag is featured in the center of Turkmenistan’s coat of arms. Named world champion Akhal-Teke in 1999, Yanardag was subsequently acquired by Saparmurat Niyazov.[6][21] In October 2013, Turkmenistan announced their intention to create a monument in honour of Niyazov's favourite horse. Yanardag's golden monument was unveiled in 2014 in Ashgabat.[22][23]

Akhal-Teke and Mitochondrial Genomes

Research published in June, 2024 by the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (CH) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (USA), supports previous studies suggesting a genealogy potentially spanning back 3,000 years.

The study analyzed DNA from the remains of horses unearthed from the Shihuyao tombs. These were found to date from the Han and Tang Dynasties in Xinjiang, China (approximately 2200 to 1100 years ago). Two high-quality mitochondrial genomes were acquired and analyzed using next-generation sequencing.

A close genetic affinity was observed between the horse of the Tang Dynasty and Akhal-Teke horses according to the primitive horse haplotype G1. Historical evidence suggests that the ancient Silk Road had a vital role in their dissemination. Additionally, the matrilineal history of the Akhal-Teke horse was accessed and suggested that the early domestication of the breed was for military purposes.

The study represents the first identification of the original nucleotide position of the Akhal-Teke in ancient horses from China. A possible dispersal route of Akhal-Teke maternal lineages was also discovered, supported by the history of extensive trade and cultural exchanges along the Silk Road. This suggests that the demand for military horses played an important role in the early domestication of the Akhal-Teke in this particular historical context. [24]

Personal life

Kyarizov is married to Yulia Serebryannik and has two children, Daud and Sofia.[25][12] Kyarizov is a Fellow of The Royal Geographic Society (FRGS) and member of the Long Riders' Guild,[26] an international association of equestrian explorers based in Zurich, Switzerland.[27][28]

The Finnish Ambassador’s Parrot

In 1993, Niyazov gifted then UK Prime Minister John Major with an Akhal-Teke called Maksat. A British diplomat from the Moscow embassy was despatched to arrange quarantine. After many hours delay, the diplomat pleaded with the receptionist on behalf of the “poor Turkmen horses”, who had been “standing up in a railway carriage for four and a half days”, eliciting in response... “the sad tale of the Finnish ambassador’s parrot”, whose fate was never revealed.[29][30][31]

See also

References

- ^ "Turkmenistan: Further information". Amnesty International. 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Geldy Kyarizov" (PDF). Amnesty International. 21 February 2007.

- ^ "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights" (PDF). United Nations. 23 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Striding So Fast on Quivering Springs". The Nation. 31 October 2024.

- ^ "Human rights abuse in Turkmenistan". European Parliament. 18 January 2007.

- ^ a b "FIVE MONTHS IN THE SECRET OVADAN DEPE PRISON" (PDF). Prove They Are Alive. 8 October 2015.

- ^ "Geldy Kyarizov v. Turkmenistan". Centre for Civil and Political Rights. 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b "LANDMARK DECISION BY THE UN". Justice pour Tous Internationale. 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Views adopted by the Committee under article 5 (4)". United Nations. 23 September 2024.

- ^ a b "United Nations Human Rights Committee" (PDF). Justice pour Tous Internationale. 5 September 2024.

- ^ a b c "Torture By Hunger"". Radio Free Europe. 5 December 2015.

- ^ a b c "Turkmenistan Holds 14-Year Old Hostage". The Diplomat. 1 September 2015.

- ^ "THE INCREDIBLE AKHAL TEKE HORSE". Turkmen Yurt TV. 31 May 2017.

- ^ "United Nations: CCPR/C/141/D/3097/2018" (PDF). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Turkmenistan". U.S. Department of State. 13 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkmenistan: Expert Blocked From Leaving Country". Human Rights Watch. 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Former prisoner denied urgent medical care: Geldy Kyarizov". Amnesty International. 28 January 2014.

- ^ "Turkmenistan: 14-Year-Old Barred From Leaving Country". Human Rights Watch. 18 September 2015.

- ^ "Divine Horses and Political Injustice". The Long Riders Guild. 8 February 2011.

- ^ Suttle, Gill. (2010). Black Sands and Celestial Horses: Tracks Over Turkestan. Scimitar Press. pp. 44–47. ISBN 978-0953453627.

- ^ "Turkmenistan: Legendary Horses Look To Make Comeback". Radio Free Europe. 26 September 2006.

- ^ "Turkmenistan: Monument honours ex-leader's horse". BBC. 7 October 2013.

- ^ "This Country Dedicates a National Holiday to Horses". National Geographic. 30 April 2018.

- ^ "Ancient Mitochondrial Genomes Provide New Clues in the History of the Akhal-Teke Horse in China". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 15 June 2024.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ "Turkmenistan". Human Rights Watch. 12 January 2025.

- ^ "Long Riders aim to circle the globe". Horse and Hound. 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Fellowship of the Society: 1082648". Royal Geographic Society. 18 June 2015.

- ^ "Attack on Geldy Kyarizov's family, Exit from Turkmenistan Denied". Crude Accountability. 18 August 2015.

- ^ "Papers reveal saga of horse given to John Major by Turkmenistan". The Guardian. 28 December 2018.

- ^ "John Major's gift horse... and other Foreign Office tales". BBC. 21 September 2012.

- ^ "John Major's gift horse". The Independent. 28 December 2018.

Attribution:

- Siqi Zhu, Naifan Zhang, Jie Zhang, Xinyue Shao, Yaqi Guo, Dawei Cai (2024), Ancient Mitochondrial Genomes Provide New Clues in the History of the Akhal-Teke Horse in China, Basel, Switzerland: MDPI

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)