Gladys Cromwell

Gladys Cromwell | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 28, 1885 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 19, 1919 (aged 33) Atlantic Ocean |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Language | English |

| Notable works | The Gates of Utterance and Other Poems (1915) |

Gladys Cromwell (November 28, 1885 – January 19, 1919) was an American poet and Red Cross volunteer during World War I. Known for her introspective and melancholic poetry, Cromwell published works in prominent literary magazines and released a volume of poems titled The Gates of Utterance and Other Poems in 1915.

Her service in the Red Cross alongside her twin sister, Dorothea, exposed her to the harrowing realities of war, which profoundly affected her mental health. The sisters died by suicide while returning to the United States in 1919.

Posthumously, Cromwell's poetry was celebrated, earning her the Poetry Society of America's prize in 1920, and her contributions to literature and war service are considered a poignant reflection of her era.[1][2]

Biography

Early life

Gladys Louise Husted Cromwell was born on November 28, 1885, in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents, Frederick Cromwell, a trustee of the Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York,[3][4] and Esther Whitmore Husted, were prominent members of New York society. Through her father Cromwell was a direct descendant of Oliver Cromwell.[4] Apart from her twin sister Dorothy, Cromwell also had three older siblings Mary "May", Seymour Legrand and Ellis. The youngest brother Ellis passed away in 1892 when Cromwell was seven years old.

The family split their time between their residence in Manhattan[4] (No. 3 West 56th) and their estate Ellis Court[4] in Bernardsville.

Education

The Cromwell sisters were privately tutored, one of their governesses being Mary Horgan, who would later marry John Mowbray-Clarke. Horgan and the Cromwell sisters would keep in contact even after Horgan quit her position and maintained a mentor and protege like relationship. The sisters would attend gatherings with writers and artists at the Sunwise Turn bookstore, owned by Mowbray-Clarke and Madge Jenison.

Cromwell later received her education at Brearley, a private school, and traveled extensively throughout Europe[2][5] together with Anne Dunn (an old teacher from her Brearley days)

The sisters debuted into New York society in 1906 [6]at the age of twenty-three. Though considered rather shy, Cromwell and her sister did indeed partake in social affairs and were members of the social club Ladies' Four-in-Hand Club[7] (a counter-part of the male members only Coaching Club)

Literary pursuits

But when a lyric theme invites,

I reach outlying bowers

Where dwell the bards of quiet years;

I join my song to theirs;

My glad, unfettered spirit hears

The melody it shares.

Cromwell began writing poetry at a young age. However, her family was initially opposed to her publishing work, viewing it as an intrusion on their privacy. Despite this, Cromwell managed to publish several poems in magazines such as Harper's Magazine[8], Poetry and The New Republic under the pseudonym Helen Jaffreys[1] Her first collection of poetry, The Gates of Utterance and Other Poems, was published in 1915.[2]

_(page_347_crop).jpg)

In 1916, the Cromwells would take a step further on the road to independence when they together rented an apartment on the corner of Park Avenue and 61st Street, at 535 Park Avenue.[9][10][11]

World War I and death

The entry of the United States into World War I in April 1917 significantly impacted Gladys Cromwell's life and career. In January 1918, she and her twin sister, Dorothea, joined the American Red Cross.[5] Their decision can perhaps be understood by the influences present within their personal life. Cromwells older sister May, who was living in Paris was already active as a relief worker in 1916, helping Belgian war orphans and Cromwells sister-in-law Agnes held a position on the Committee on Women's Service as treasurer. The committee worked closely with the Red Cross and its main purpose was to employ women instead of men in non-combatant roles ,such as relief work. Furthermore the sister felt it was duty of theirs[12] ;

...to go to Europe as war workers, since no male member of the family was acceptable for military service. I was from the beginning discouraging about their going, knowing how unprepared they were to face what they would have to experience as nurses and canteen workers. They were rather nervous of men and had no notion at all of what war conditions or soldiers were like; they had lived such a sheltered life that they had never been in the subway or a public conveyance of any kind until just before they left for France.

— Molly Gunning Colum

Their decision shocked their family and friends

The sisters were deployed to France, where they served as canteen workers in Chalons-sur-Marne and later at evacuation hospitals.[3] Their roles exposed them to the constant threats of air raids and the relentless stress of being close to the front lines, which affected their mental and physical health.[2]

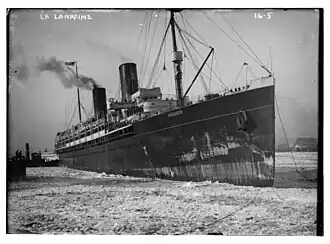

By the end of the war, the Cromwell sisters were deeply impacted by their experiences.[5] In January 1919, they boarded the French liner La Lorraine in Bordeaux to return to New York. Concerned colleagues, including Dr. C. L. Purnell, noted their fragile state, describing them as "tired, nervous, and hysterical." Despite administering sedatives, the efforts to stabilize their condition proved insufficient.[2]

On the evening of January 19, 1919, Gladys and Dorothea Cromwell died by suicide. Edward Pemberton, a sentry on La Lorraine, witnessed the sisters on the deck at around 7:00 P.M. He saw one sister suddenly climb the rail and jump overboard, followed immediately by the other. Although Pemberton quickly reported the incident, the ship had already traveled five miles from the location of their jump by the time the alarm reached the captain, making any rescue attempt futile.[2]

The Cromwell sisters left behind three notes addressed to Major James C. Sherman, their brother Seymour L. Cromwell, and their sister-in-law. The contents of these letters were not disclosed to the public.[2] Their wills, dated January 2, 1919, contained a clause indicating a possible premeditation of their actions: "If my sister and myself die in or as the result of any common disaster or catastrophe, whether simultaneously or otherwise".[13]

A memorial service for the sisters was held on February 5, 1919, at St. Bartholomew's Church in Manhattan.[3] Their bodies were recovered three months later and were buried in France with full military honors.[2]

Posthumous recognition

In recognition of their service, the French government posthumously awarded them the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille de Reconnaissance française. A second volume of her poetry, Poems (1919), was published posthumously,[5] comprising works from her earlier book as well as previously unpublished poems. Poems shared the 1920 prize from the Poetry Society of America with John G. Neihardt's The Song of Three Friends. Her poetry, characterized by a melancholic and introspective tone, reflected both the personal and collective traumas of her time.[2]

Despite her early death, Cromwell's work was well-received during her lifetime, with contemporary critics praising her lyrical quality. In a review of her first book in the New Republic, Padraic Colum referred to her as "a younger sister of the great poets."[2]

References

- ^ a b Halley, Catherine (November 9, 2022). "Strange, Inglorious, Humble Things". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patton 2000.

- ^ a b c Richman, Jeff (January 23, 2017). "A Twin Tragedy". Green Wood. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Weeks, Lyman Horace (1898). Prominent Families of New York: Being an Account in Biographical Form of Individuals and Families Distinguished as Representatives of the Social, Professional and Civic Life of New York City. Historical Company.

- ^ a b c d "Modernist Journals | Cromwell, Gladys (1885-1919)". Modernist Journals Project. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ "2 Dec 1906 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle". Brooklyn Eagle. December 2, 1906. p. 13. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ Downing, Paul H. (April 1, 1967). The Carriage Journal: Vol 4, No 4, Spring 1967. Carriage Assoc. of America. p. 150.

- ^ Harper's New Monthly Magazine. Harper's Magazine Company. 1908.

- ^ "Leases" (PDF). Columbia University Libraries. Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. 1916.

- ^ "Atlanta Georgian. (Atlanta, Ga.) 1912-1939, January 30, 1919, Evening Edition, Page 3, Image 3 « Georgia Historic Newspapers". gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ Richman, Jeff (January 23, 2017). "A Twin Tragedy". Green-Wood. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ Halley, Catherine (November 9, 2022). "Strange, Inglorious, Humble Things". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

- ^ "WILLS OF CROMWELL TWINS.; Sisters Who Leaped off Steamship Make Identical Bequests". The New York Times. March 5, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

Sources

- Patton, Venetria K. (2000). "Cromwell, Gladys". American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1600386. (subscription required)