Haud

Haud

Hawd هَود هاود | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regions | Marodi Jeh, Togdheer, Sool, ( Somali Region, ( |

| Area | |

• Total | 119,000 km2 (46,000 sq mi) |

The Haud (also Hawd) (Somali: Hawd, Arabic: هَوْد), formerly known as the Hawd Reserve Area, is a plateau situated in the Horn of Africa consisting of thorn-bush and grasslands.[1] The region includes the southern part of Somaliland as well as the northern and eastern parts of the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[2][3] Haud is a historic region as well as an important grazing area and has multiple times been referenced in countless notorious poems. The region is also known for its red soil, caused by the soil's iron richness.[4] The Haud covers an estimated area of about 119,000 square km (or 46,000 square miles), more than nine-tenths the size of England, or roughly the size of North Korea.[5]

History

The Haud region, a vast plateau in the Horn of Africa, has historically been a significant area inhabited primarily by Somali pastoralist clans. It is part of the larger Somali ethnic territories.

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The Haud is believed by some scholars to have been part of the ancient Land of Punt, a kingdom renowned to the ancient Egyptians for its wealth in incense, gold, and exotic animals[6]. The exact geographical boundaries of Punt remain debated, but many suggest it encompassed parts of the Horn of Africa, including the Haud.

During the medieval era, the Haud region came under the influence of the Ifat Sultanate, an Islamic kingdom which flourished from the late 13th to the early 15th centuries.[7]Ifat controlled parts of what are now eastern Ethiopia and Djibouti. After Ifat’s decline, the Adal Sultanate rose to prominence, continuing to assert Islamic cultural and political influence in the region.[8]

The Isaaq Sultanate

By the 18th century, the Haud was central to the Isaaq Sultanate, governed by the Rer Guled Eidagale branch of the Garhajis clan within the Isaaq clan-family.[9] The sultanate’s authority extended across parts of present-day Somaliland and Ethiopia, with capitals at Toon and later Hargeisa. The Isaaq Sultanate played an essential role in the political, social, and economic life of the region until the late 19th century.[10]

Colonial Era and the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty

European colonial expansion dramatically reshaped the Haud. The 1941 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty saw Britain cede the Haud and Ogaden regions to Ethiopian sovereignty.[11]This transfer was contentious since the Haud was predominantly inhabited by ethnic Somalis, many of whom had been under British protection as part of British Somaliland.[12] The treaty ignored Somali claims to the land, fueling long-standing resentment.

Despite the formal cession, Britain continued to administer the Haud as part of its Somaliland Protectorate for 13 years, effectively acting as a buffer between Ethiopian authorities and Somali pastoralists.[13] The 1954 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement reaffirmed Ethiopian sovereignty, intensifying tensions as Ethiopia sought to assert stronger control over the region.[14]

Post-Colonial Period and the Ogaden War

Following Somali independence in 1960, the Somali government adopted irredentist ambitions to unify all Somali-inhabited territories, including the Haud and Ogaden, into a Greater Somalia.[15] These claims heightened tensions with Ethiopia.

In 1977, Somalia invaded the Ogaden and Haud regions, igniting the Ogaden War (1977–1978). Somali forces initially occupied much of the Haud, including key towns like Jigjiga.[16]However, Ethiopia, with Soviet and Cuban support, repelled the invasion.[17] The war entrenched animosities and complicated the Haud’s political future.[18]

Background and Causes of the Afraad Rebellion

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Haud became a site of intense conflict and abuses against the Isaaq clan. The Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF), primarily composed of Ogaden fighters and backed by the Somali National Army (SNA), waged armed struggle against Ethiopia.[19]However, some WSLF and SNA units perpetrated massacres, looting, rape, and destruction targeting Isaaq civilians in the Haud.[20]

The Isaaq repeatedly appealed to both the WSLF and the Somali government to end these atrocities, but their pleas were ignored.[21] The SNA's support of the WSLF further enabled continued abuses, deepening grievances.[22]

In response, Isaaq officers and fighters from the WSLF’s Fourth Brigade—known locally as the Afraad—rebelled in 1978. Rejecting WSLF leadership’s complicity, they launched an independent insurgency focused on defending Isaaq territories.[23]Led by figures such as Mohamed Farah Dalmar Yusuf, Afraad engaged in guerrilla warfare across Gobyar, Dhaberooble, Wajaale, and Gaashaamo.[24]

By 1982, Afraad had gained broad Isaaq support, expelled many WSLF fighters from the Haud, and formally joined the Somali National Movement (SNM), the main resistance group for Somaliland autonomy.[25]

Culmination into the Somaliland War

The Afraad rebellion was a catalyst for wider Isaaq opposition to the Somali government. Continued government repression and refusal to protect Isaaq civilians led to the escalation of the Somaliland War throughout the 1980s.[26] The conflict saw harsh counterinsurgency tactics, including aerial bombings and mass atrocities by the Somali regime.[27] The war ultimately resulted in the collapse of the Siad Barre regime and Somaliland’s declaration of independence in 1991.[28]

The 2024 Dacawaley Conflict and Liyu Police Involvement

In December 2024, the Haud region became a focal point of the Dacawaley conflict, centered in the pastoralist settlement of Dacawaley in Ethiopia’s Somali Regional State.[29]The conflict involved inter-clan clashes primarily between the Isaaq and Ogaden clans over grazing lands and resources.[30]

The situation escalated when the Liyu Police, an Ethiopian regional paramilitary force aligned with the Somali Regional State government, intervened.[31] Reports indicated severe abuses, including attacks on civilians, destruction of property, and dozens killed.[32] Violence peaked from December 19 to 25, 2024, resulting in over 35 casualties and mass displacement.[33]

Elders attempting mediation were ambushed and some abducted, worsening the conflict.[34] The Liyu Police’s role was condemned by Ethiopian federal authorities and Somaliland officials.[35]

Subsequently, Ethiopian federal forces took control of security in the region, and agreements were reached to remove the Liyu Police from Dacawaley.[36] Joint Ethiopian-Somaliland talks in Jigjiga sought to reduce tensions and address land and resource disputes.[37]

Humanitarian Impact

The 2024 conflict caused significant humanitarian suffering. Hundreds were displaced, homes and livelihoods destroyed, and vital livestock lost.[38]

Overview

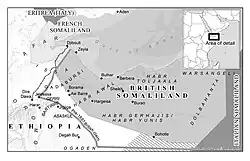

The Haud is of indeterminate extent; some authorities consider it denotes the part of Ethiopia east of the city of Harar. I.M. Lewis provides a much more detailed description, indicating that it reaches south from the foothills of the Golis and Ogo Mountains, and is separated from the Ain and Nugal valleys by the Buurdhaab mountain range.[39] "The northern and eastern tips lie within the Somali Republic, while the western and southern portions (the later merging with the Ogaden plateau) form part of the Harari Province of Ethiopia."[40] For decades it (as well as the entire Ogaden) has been an area of conflict and controversy. The eastern portion of Haud is traditionally referred to as Ciid.[41] Due to its lack of permanent wells except to its west, the region is for the most part uninhabited during the dry season (January to April) when the nomads cross into Somaliland for grazing.[2]

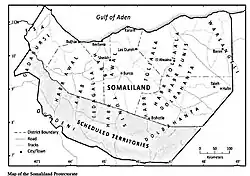

The British exerted control of the Ogaden beginning in 1941 as part of the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement, administering the Haud as part of the British Somaliland protectorate, although Ethiopian sovereignty was still recognized in the area.[42] This region was defined in the 1942 agreement as including the Ethiopian territory within a continuous belt of Ethiopian territory 25 miles [40km] wide contiguous to the frontier of French Somaliland running from the frontier of Eritrea to the Franco-Ethiopian Railway. Thence south-west along the railway to the bridge at Haraua. Thence south and south-east, excluding Gildessa, to the north-eastern extremity of the Garais Mountains and along the crest of the ridge of these mountains to their intersection with the frontier of the former Italian colony of Somalia. Thence along the frontier to its junction with British Somaliland.[43]

Topography

The terrain of the Haud consists mainly of plains.[5] The plateau is covered by a characteristic red sand, which conceals solid rocks like Nubian, Lower and Middle Eocene limestones as well as gypseous shales.[5] In the Sool region there is a central area consisting of Middle Eocene anhydrite.[5]

The region is largely covered by bushes, with many species of Acacia and other trees that measure up to 6-10 metres in height with much grass.[5] There is also vast stretches of bush-less grassy plains referred to as ban in Somali.[5] The region is filled with anthills rising up to 7 metres in height.[5]

Flora and fauna

The region is home to a wide variety of fauna including lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas and jackals, as well as many species of antelopes, wart-hogs and a wide array of other smaller animals. The Haud is also home to the Somali ostrich, which is endemic to the region.[5]

Cessation to Ethiopia

In 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of Somalis,[44] the British signed the Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement and gave Haud and the Somali Region to Ethiopia, based on the earlier Anglo-Ethiopian treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somaliland territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against raids by Somali clans.[45] Britain included the proviso that the Somali residents would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over the area.[46] This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to buy back the Somaliland territory that it had turned over[46] (which some presume was a "protectorate" by British treaties with the Somali clans in 1884 and 1886).

_(18411100885).jpg)

Haud delegation

In response to the cessation of Haud Reserve and the Ogaden regions to Ethiopia in the year 1948, the fifth Grand Sultan of the Isaaq, Abdillahi Deria, led a delegation of politicians and Sultans, including the Habr Awal Sultan Sultan Abdulrahman Sultan Deria and political activist and heavyweight Michael Mariano of the Habr Je'lo, to the United Kingdom in order to petition and pressure the government to return them.[47]

In Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960, Historian Jama Mohamed writes:

The N.U.F. campaigned for the return of the territories both in Somaliland and abroad. In March 1955, for instance, a delegation consisting of Michael Mariano, Abokor Haji Farah and Abdi Dahir went to Mogadisho to win the support and co-operation of the nationalist groups in Somalia. And in February and May 1955 another delegation consisting of two traditional Sultans (Sultan Abdillahi Sultan Deria, and Sultan Abdulrahman Sultan Deria), and two Western-educated moderate politicians (Michael Mariano, Abdirahman Ali Mohamed Dubeh) visited London and New York. During their tour of London, they formally met and discussed the issue with the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Alan Lennox-Boyd. They told Lennox-Boyd about the 1885 Anglo-Somali treaties. Under the agreements, Michael Mariano stated, the British Government 'undertook never to cede, sell, mortgage or otherwise give for occupation, save to the British Government, any portion of the territory inhabited by them or being under their control'. But now the Somali people 'have heard that their land was being given to Ethiopia under an Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897'. That treaty, however, was 'in conflict' with the Anglo-Somali treaties 'which took precedence in time' over the 1897 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty[.] The British Government had 'exceeded its powers when it concluded the 1897 Treaty and ... the 1897 Treaty was not binding on the tribes.' Sultan Abdillahi also added that the 1954 agreement was a 'great shock to the Somali people' since they had not been told about the negotiations, and since the British Government had been administering the area since 1941. The delegates requested, as Sultan Abdulrahman put it, the postponement of the implementation of the agreement to 'grant the delegation time to put up their case' in Parliament and in international organizations.[48]

Demography

The Haud is primarily inhabited by the Isaaq clan-family, most notably the Garhajis, Habr Awal, Habr Je'lo and Arap clans, and is part of the wider clan-family's core traditional territory.[49][50] Several subclans of the Darod clan are also a present minority in the region, most notably the Ogaden, Jidwaaq.[51] Dhulbahante[52][49][53]

Notable towns in Haud

See also

- Somali Acacia–Commiphora bushlands and thickets, the ecoregion that includes the Haud.

Notes

- ^ Brandt, Steven A.; Carder, Nanny (1987). "Pastoral Rock Art in the Horn of Africa: Making Sense of Udder Chaos". World Archaeology. 19 (2): 194–213. doi:10.1080/00438243.1987.9980034. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 124551.

- ^ a b "Hawd Plateau | plateau, East Africa". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ Deblauwe, Vincent; Couteron, Pierre; Bogaert, Jan; Barbier, Nicolas (2012). "Determinants and dynamics of banded vegetation pattern migration in arid climates". Ecological Monographs. 82 (1): 3–21. Bibcode:2012EcoM...82....3D. doi:10.1890/11-0362.1. ISSN 0012-9615. JSTOR 23206682.

- ^ "Hawd Pastoral Livelihood Zone Baseline Profile, August 2011 - Somalia". ReliefWeb. 19 August 2011. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Macfadyen, W. A. (1950). "Vegetation Patterns in the Semi-Desert Plains of British Somaliland". The Geographical Journal. 116 (4/6): 199–211. Bibcode:1950GeogJ.116..199M. doi:10.2307/1789384. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1789384.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. (2011-08-01). "Punt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Russell, Jesse; Cohn, Ronald (July 2012). Adal Sultanate. Book on Demand. ISBN 978-5-511-07077-3.

- ^ "The Ethiopian-Adal War 1529-1543 | From Retinue to Regiment 1453-1618 | Helion & Company". www.helion.co.uk. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Lewis, I.M. *A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa*. Oxford University Press, 1961.

- ^ Adam, Hussein Mohamed. *Somalia and the World: Proceedings of the Somali Studies International Association*. 1995.

- ^ Geshekter, Charles L. (1985). "Anti-Colonialism and Class Formation: The Eastern Horn of Africa before 1950". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 18 (1): 1–32. doi:10.2307/217972. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 217972.

- ^ Lewis, I.M. *Understanding Somalia and Somaliland: Culture, History and Society*. Hurst & Company, 2008.

- ^ Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye. *Culture and Customs of Somalia*. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001.

- ^ Marcus, Harold G. *A History of Ethiopia*. University of California Press, 1994.

- ^ Gebru Tareke. *The Ethiopia-Somalia War of 1977 Revisited*. International Journal of African Historical Studies, 2000.

- ^ 18 Wings Over Ogaden The Ethiopian Somali War 1978 1979.

- ^ Woodward, Peter. *US Cold War Strategy and the Horn of Africa*. 2009.

- ^ Healy, Sally. *Ending Africa’s Wars: Progressing to Peace*. Polity, 2009.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1994). Blood and Bone: The Call of Kinship in Somali Society. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-93-6.

- ^ Waal, Alex De; Watch (Organization), Human Rights (1991). Evil Days: Thirty Years of War and Famine in Ethiopia. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-038-4.

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 1994.

- ^ Mohamoud, Abdullah A. (2006). State Collapse and Post-conflict Development in Africa: The Case of Somalia (1960-2001). Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-413-2.

- ^ Richards, Rebecca (2016-02-24). Understanding Statebuilding: Traditional Governance and the Modern State in Somaliland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-00466-0.

- ^ SNM Archives, 1982.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (2008). Understanding Somalia and Somaliland: Culture, History, Society. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-898-6.

- ^ Human Rights Watch. "Somalia: A Government at War with Its Own People." 1990.

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 1990.

- ^ Drysdale, John. *Whatever Happened to Somalia?* Haan Publishing, 1994.

- ^ "Dacawaley Conflict Escalates Amid Rising Tensions in Ethiopian Somali Region - Mustaqbal Media". Mustaqbal Media - (English). 2024-12-25. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ admin (2024-12-26). "Somaliland accuses Police Forces of the Somali Regional State of Ethiopia of massacring local people in the Dacawaley – Somali Dispatch". Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Human Rights Watch, "Ethiopia: Abuses in Somali Region Conflict," December 2024.

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 2024.

- ^ Addis3 (2024-12-26). "At least 35 killed in land dispute clashes between "pastoralists and gov't militias" in Dacawaley, Somali region: Sources". Addis Standard. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ AFP, "Mediation efforts in Ethiopia's Somali region disrupted," December 2024.

- ^ Addis3 (2024-12-28). "Ethiopia, Somaliland agree to end hostilities in Dacawaley after deadly land dispute claims dozens in Somali region - Addis Standard". Addis Standard. Archived from the original on 2025-02-17. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ AP News, "Federal troops replace regional forces in Ethiopia’s Somali area," January 2025.

- ^ "Somaliland and Ethiopia reach deal to end deadly Dacawaley conflict". www.hiiraan.com. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Addis3 (2024-12-26). "At least 35 killed in land dispute clashes between "pastoralists and gov't militias" in Dacawaley, Somali region: Sources". Addis Standard. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The South African Geographical Journal: Being a Record of the Proceedings of the South African Geographical Society. 1945. p. 44.

- ^ I.M. Lewis, A Modern History of the Somali, fourth edition (Oxford: James Currey, 2002), pp. 2f

- ^ Journal of the Anglo-Somali Society - Issues 30-33, 2001 - PAGE 18

- ^ According to the map in John Spencer, Ethiopia at Bay: A personal account of the Haile Selassie years (Algonac: Reference Publications, 1984), pp. 186f, the Haud covered an area adjacent to British Somaliland south of 9° latitude and covering the modern woredas of Aware, Misraq Gashamo, Danot and Boh.

- ^ Quoted in D. J. Latham Brown, "The Ethiopia-Somaliland Frontier Dispute", International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 5 (1956), pp. 256f

- ^ Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38

- ^ David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.73

- ^ a b Aristide R. Zolberg et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106

- ^ Mohamed, Jama (2002). Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960. The English Historical Review.

- ^ Mohamed, Jama (2002). Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960. The English Historical Review.

- ^ a b "Report on Mission to Haud Area, Region 5". www.africa.upenn.edu. UNDP Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ Sugule, Jama; Walker, Robert. "Changing Pastoralism in Region 5". The Africa Center - University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ Abdullahi, Abdi M. (2007). "The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF): The Dilemma of Its Struggle in Ethiopia". Review of African Political Economy. 34 (113): 556–562. ISSN 0305-6244. JSTOR 20406430.

- ^ Rodd, Francis James Rennell Rodd Baron Rennell of; Rennell, Francis James Rennell Rodd Baron (1948). British Military Administration of Occupied Territories in Africa During the Years 1941-1947. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 488.

- ^ "REPORT ON MISSION TO". www.africa.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

Further reading

- Theodore M. Vestal, "Consequences of the British Occupation of Ethiopia During World War II".

- Leo Silberman, Why the Haud was ceded, Cahiers d'études africaines, vol. 2, cahier 5 (1961), pp. 37–83.