Kōhei Akagi

Kōhei Akagi | |

|---|---|

赤木 桁平 | |

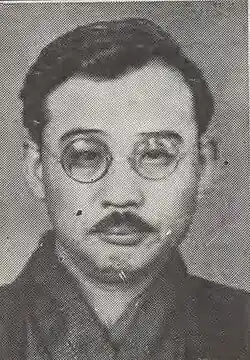

Akagi in 1937 | |

| Member of the House of Representatives | |

| In office 20 February 1936 – 6 December 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Katsuharu Aota |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Constituency | Osaka 3rd |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 February 1891 Niimi, Okayama, Japan |

| Died | 10 December 1949 (aged 58) |

| Political party | IRAA (1940–1945) |

| Other political affiliations | Rikken Minseitō (1932–1940) |

| Education | Takahashi High School Six Higher School |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

Akagi Kohei (Japanese: 赤木 桁平, Hepburn: Akagi Kōhei, born Tadayoshi Ikezaki (Japanese: 池崎 忠孝, Hepburn: Ikezaki Tadayoshi, who also later used the name Chūkō), formerly Akagi (赤木), February 9, 1891 – December 10, 1949)[1] was a Japanese critic and politician. He was the first person to write a biography of Natsume Sōseki and gained fame in the Taishō period for his campaign against so-called "dissipated literature" (yūtō bungaku). He served three terms as a member of the House of Representatives, being elected in the 19th, 20th, and 21st general elections.[2]

Early life and education

Akagi was born in Manzai Village, Atetsu District, Okayama Prefecture (present-day Niimi City).[1] His father, Tatsusaburō Akagi, worked in surveying for the Mitsubishi-affiliated Yoshioka Copper Mine but resigned after clashing with the company and attempted to start his own mining development. However, he went bankrupt when Kohei was 18. After graduating from the former Okayama Prefectural Takahashi Junior High School (now Okayama Prefectural Takahashi High School), Akagi attended the Sixth Higher School before entering the Faculty of Law (German Law course) at Tokyo Imperial University.[1]

While still a student at the Sixth Higher School, he was adopted into the family of hosiery businessman Kozaburō Ikezaki of Shijō Village in Kitakawachi District, Osaka Prefecture (present-day Daitō City), on the condition that his tuition be paid. He published a critique of Suzuki Miekichi in the school magazine, and in 1912 (Taishō 1), through Miekichi’s mediation, he published Shin Jidai no Shohanbun ("Modern Age Letter Writing").[1]

Literary career

After enrolling at Tokyo Imperial University’s Faculty of Law in 1913, Akagi joined the literary circle of Natsume Sōseki through Miekichi’s introduction and began writing literary criticism under the pen name “Akagi Kohei,” which was given to him by Sōseki. He was among the first critics to positively evaluate the Shirakaba school.[1]

One of his most famous works was the article “The Eradication of 'Dissipated Literature’” (Yūtō Bungaku no Bokumetsu), published in the Yomiuri Shimbun from August 6 to 8, 1916, and later included in Artistic Idealism (Geijutsu-jō no Risōshugi) in October. In this critique, Akagi attacked novels set in the pleasure quarters, particularly the Jōwa Shinshū ("New Collection of Romantic Tales") series,[note 1] labeling them as "dissipated literature." His main target was Chikamatsu Shūkō, but others including Osada Mikihiko, Yoshi Ikō, Kubota Mantaro, and Gotō Sueo were also criticized.[1]

The piece sparked a major controversy. Critics pointed out that Kubota and Gotō had not written much about the pleasure quarters, and Osanai Kaoru, a key figure in non-Sōseki circles at Tokyo Imperial University, questioned why he and Nagai Kafū had not been targeted. Tanizaki Jun’ichirō also escaped criticism, which led to speculation that Akagi refrained due to personal ties—he was close to Tanizaki at the time and respectful toward Kafū, Tanizaki’s patron. Some retorted that only Sōseki and Ogawa Mimei could be said to write literature entirely devoid of "dissipated" content.

Journalistic career

After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University in 1917, Akagi joined the Yorozu Chōhō newspaper as an editorial writer.[1] Though his adoptive parents opposed his marriage to their eldest daughter, the couple registered their marriage in 1918 after she became pregnant, and their son Shūkichi was born. Akagi left the newspaper following a scandal involving an actress from the Imperial Theater and returned to Osaka, where he took over the family hosiery business.[3]

Lacking business acumen, he nevertheless forged connections in the Kansai business community, befriending notable figures such as poet and Sumitomo executive Jun Kawada, Hatsujiro Yamamoto (founder of Yamahatsu Sangyo and an art collector), and Ryūji Tanabe (first president of Kansai Haiden, now Kansai Electric Power), Yamamoto and Tanabe share the same alma mater: Takahashi High School.[3]

In 1929, after his public lecture was praised by Kodama Hamago, an executive of the Nomura conglomerate, Akagi published the lecture transcript America Is Nothing to Fear (米国怖るゝに足らず) under his real name Ikezaki Tadayoshi. It became a bestseller and launched his prolific career as a writer advocating the inevitability of war with the United States.[3]

Political career

In 1932, he ran unsuccessfully in the 18th general election for the House of Representatives. However, he was elected in the 19th election in 1936, representing Osaka’s 3rd district.[1] In 1937, during the first Konoe Cabinet, he served as a Ministry of Education advisor and had frequent contact with Kido Kōichi during the second Konoe Cabinet. He also played a key role in the 1943 founding of the Greater Japan Student Aid Foundation (Dai-Nihon Ikueikai).[3]

Arrest and later life

On December 2, 1945, the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ) ordered the Japanese government to arrest Akagi as one of the 59 individuals on its third list of war crimes suspects.[4] He was detained at Sugamo Prison on suspicion of being a Class-A war criminal. He resigned from the House of Representatives on December 6, 1945.[5] Although he was later released due to illness, he was purged from public office and died in obscurity.[6]

Works

As Kohei Akagi

- Geijutsujō no Risōshugi [Idealism in the Arts], Rakuyōdō, 1916

- Natsume Sōseki, Shinchosha, 1917

- Kindai Kokoro no Shozō [Phenomena of the Modern Mind], Oranda Shobō, 1917

- Takayama Chogyū as a Man and Thinker, Shinchosha, 1918

- Taishi Shogyōsan [Praise of Prince Shōtoku’s Deeds], Ōmura Shoten, 1921

As Tadayoshi Ikezaki

- America Need Not Be Feared, Senshinsha, 1929

- Japanese Submarines: Pacific Operations and Submarine Warfare, Senshinsha, 1929

- Americanism as a Global Threat, Tenjinsha, 1930

- A Farewell to My Late Friend Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, Tenjinsha, 1930

- The Fall of the British Empire Has Come, Senshinsha, 1931

- Can a 60% Navy Fight?: Continuation of "America Need Not Be Feared", Senshinsha, 1931

- A Proper Understanding of the Manchurian-Mongolian Problem, Tenjinsha, 1931

- Theory on the Present State of Britain and America: The Rise of the U.S. and the Fall of the U.K., Senshinsha, 1932

- The Inevitable U.S.-Japan War, Senshinsha, 1932

- Pacific Strategy Theory, Senshinsha, 1932

- The Rise of the Genius Empire Japan, Shinkōsha, 1933

- Recent Studies on Military Issues, Ōmura Shoten, 1936

- From the Perspective of National Defense, Shōshinsha, 1936

- Japan Standing in the World, Kon'nichi no Mondai-sha, 1937

- Will Britain Dare to Challenge?, Daiichi Shuppansha, 1937

- Keep Watch on the Soviet Union, Daiichi Shuppansha, 1937

- Memoirs of the World War, Daiichi Shuppansha, 1938

- New China Theory, Modern Japan Company, 1938

- New China and the New Life Movement, Meguro Shoten, 1939

- Singapore as a Strategic Base: Britain’s Far East Strategy, Daiichi Shuppansha, 1939

- Recent Japanese Foreign Policy: A Study, Daiichi Shuppansha, 1939

- If the U.S.-Japan War Comes: The Theory and Practice of the Pacific War, Shinchosha, February 1941

- A Brief Account of Ishida Mitsunari, Okakura Shobō, 1942

- Certain Victory in a Prolonged War, Shinchosha, 1942

- Praise of Prince Shōtoku, Okakura Shobō, 1943

- Thus the World Fought: Reflections on the Global War, Shinsendō, 1943 (Selected Writings of Tadayoshi Ikezaki)

Biography

- Takumi Satō. The Light and Shadow of Tadayoshi Ikezaki: A Cultured Elitist in Mass Politics (Modern Japanese Media Politicians, Vol. 6), Sōgensha, 2023

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Okayama Prefectural Library. "Digital Okayama Encyclopedia | Reference Database." Digital Okayama Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 18, 2025.

- ^ 日本人名大辞典+Plus,367日誕生日大事典, 20世紀日本人名事典,新訂 政治家人名事典 明治~昭和,デジタル版. "赤木桁平(アカギ コウヘイ)とは? 意味や使い方". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2025-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Sawada. Modern Japanese Perceptions of America, Part II, Chapter 3: "Tadayoshi Ikezaki’s Theory of the Inevitability of War with the United States."

- ^ "Arrest Orders for 59 People Including Prince Nashimoto, Hiranuma, and Hirata" (Mainichi Shimbun, Tokyo edition, December 4, 1945). In: Shōwa News Encyclopedia, Volume 8: 1942–1945, p. 341. Published by Mainichi Communications, 1994.

- ^ Official Gazette (Kanpō), No. 5675, December 11, 1945.

- ^ Cabinet Secretariat, Administrative Inspection Division (ed.). Memorandum on Public Office Purge: List of Affected Individuals. Hibiya Political and Economic Society, 1949, p. 151. NDLJP:1276156.