Marshal of the Court (Serbia, Yugoslavia)

| Marshal of the Royal Court | |

|---|---|

| Маршал Двора | |

Royal coat of arms of Yugoslavia | |

| |

| Residence | Maršalat (Marshal's Palace), Belgrade |

| Seat | Novi Dvor, Belgrade |

| Appointer | The King |

| Formation | 1904 |

| First holder | Boško Čolak-Antić |

| Final holder | Boško Čolak-Antić |

| Abolished | 1941 |

The Marshal of the Court (Serbian: Маршал Двора, romanized: Maršal Dvora) was a senior official in the royal household of the Kingdom of Serbia and later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The officeholder served as chief courtier and was responsible for royal protocol, court ceremonies, the reception of foreign dignitaries, the internal organisation of the royal court and the command of the royal palace guard. In practice, the Marshal was a key intermediary between the monarch and both state institutions and the public.

Traditionally held by high-ranking military officers or senior diplomats, the position was held by several prominent figures, including Boško Čolak-Antić, who served as the first and last Marshal of the Court under both Peter I of Serbia and Peter II of Yugoslavia. The office was abolished in 1941 following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia and never reinstated under the post-war communist regime.[1]

Role and functions

The Marshal of the Court functioned as a great officer of the royal household, broadly equivalent to the Grand Chamberlain or Lord Steward in other European monarchies. The office oversaw court staff, scheduled audiences and ceremonies, and managed the protocol governing royal appearances and travel. The Marshal also held authority over the palace guard, which was responsible for royal security and ceremonial military duties at court. The Marshal also accompanied the monarch on official visits and state occasions, both domestic and international.[2]

The role was traditionally held by high-ranking military officers or senior diplomats, combining administrative competence with courtly decorum. The Marshal reported directly to the sovereign and worked closely with ministers, foreign envoys, and the Church hierarchy in ceremonial matters.[1]

History

Before the formal creation of the Marshal of the Court in 1904, Serbian rulers were assisted by adjutants, trusted military aides who managed court protocol and represented the monarch in public and diplomatic affairs. The first known appointments came in 1839, when Prince Miloš Obrenović named Arsenije Andrejević, Pavle Stanišić, and Živko Davidović as princely adjutants. Davidović later served Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević and rose to high military and state office.[3] Others included Đorđe Milovanović (1840–1842), Jovan Naumović (1843–1846), and Dragutin Žabarac, who took part in the 1867 Belgrade Fortress handover.[4][5]

By the 1870s, the adjutant role had become more formalised. Colonel Kosta Janković, who served Prince and then King Milan Obrenović, was appointed Marshal of the Court in 1880. General Mihailo Rašić succeeded him after serving as adjutant to King Aleksandar Obrenović.[6] At the turn of the century, prominent adjutants included Mihailo Naumović (involved in the 1903 coup), Ilija Ćirić, Živojin Mišić, and Dragomir T. Nikolajević, who accompanied King Peter during the Balkan Wars.[7]

The position was formally established in 1904, following the coronation of King Peter I of Serbia, as part of a broader institutional modernisation of the Serbian monarchy. The inaugural officeholder was Boško Čolak-Antić, who had previously served in diplomatic posts.[8] With the formation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918 (renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929), the office was retained and expanded to reflect the increased scale of the unified court. During the interwar years, the Marshal played an essential role in court life at Novi dvor and on royal tours abroad, particularly under King Alexander I of Yugoslavia.[1]

The office was abolished in 1941 following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia. The court went into exile, and the institution was never reinstated by the post-war Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[9]

Residence

The Marshal's official residence, known as the Maršalat, was located adjacent to Novi dvor, the royal residence, in central Belgrade. It was a prominent horseshoe-shaped building used both as an office and reception venue. Originally built in the mid-19th century as part of the palace guard facilities, it was later expanded and remodeled by architect Momir Korunović in 1922 to host foreign dignitaries for the royal wedding of King Alexander I and Princess Maria of Romania. Richly decorated in the Serbian national style, it contrasted sharply with the surrounding Baroque and Renaissance buildings.[10]

After the Second World War, the building briefly housed the Ethnographic Museum before being marked for demolition in the early 1950's during the redesign of the palace complex and the creation of Pioneers Park. Officially, it was removed for aesthetic reasons and to open the view toward the National Assembly, but some argue its destruction symbolized a political break with the royal past.[10]

Marshals of the Court (1904–1941)

| Portrait | Name | Tenure | Monarch(s) served | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

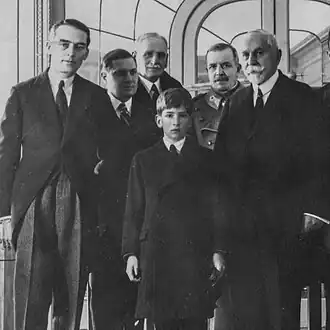

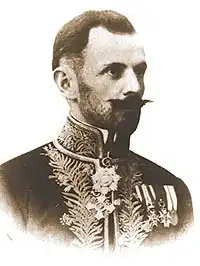

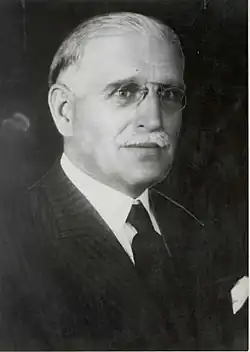

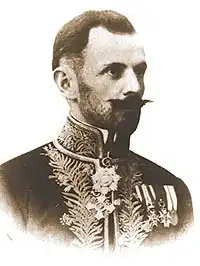

|

Boško Čolak-Antić | 1904–1907 | Peter I of Serbia | Acting Marshal; previously Minister Plenipotentiary to Bulgaria (1899–1903).[8] |

|

Petar Živković | 1917–1918 | Peter I | Later Prime Minister of Yugoslavia (1932–1934).[11] |

|

Jevrem Damjanović | 1918–1927 | Peter I, Alexander I of Yugoslavia | Served under two monarchs; oversaw early Yugoslav court transition.[1] |

|

Aleksandar Dimitrijević | 1927–1934 | Alexander I | Oversaw ceremonial affairs during interwar expansion.[1] |

|

Slavko Grujić | 1934–1935 | Peter II of Yugoslavia | Brief tenure following Alexander's assassination.[12] |

|

Boško Čolak-Antić | 1935–1941 | Peter II | Returned to office; last Marshal before the monarchy's fall.[13] |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Telegraf 2018.

- ^ Čedomir Popov & Dragoljub Živojinović 2013.

- ^ Vesti, 2023 & 1.

- ^ Vesti, 2023 & 2.

- ^ Vesti, 2023 & 3.

- ^ Vesti, 2023 & 4.

- ^ Vesti, 2023 & 5.

- ^ a b Novica Rakočević 1981, p. 35.

- ^ Marie–Janine Calic 2019, p. 275.

- ^ a b Radovanović 2021.

- ^ Mile Bjelajac 2007.

- ^ Stephen Taylor 1935, p. 336.

- ^ Robert L. Jarman 1997, p. 668.

- Works cited

- Mile Bjelajac (2007). Generals and Admirals of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1918–1941 (in Serbian). Serbian Institute of History. ISBN 978-86-7005-039-6.

- Marie-Janine Calic (2019). A History of Yugoslavia. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-838-3.

- Robert L. Jarman (1997). Yugoslavia: 1927-1937. Archive Editions Limited. ISBN 978-1-85207-950-5.

- Čedomir Popov; Dragoljub Živojinović (2013). Two Centuries of Modern Serbian Diplomacy (in Serbian). Balkan Institute SANU. ISBN 978-86-7179-079-6.

- Novica Rakočević (1981). Political relations between Montenegro and Serbia, 1903–1918 (in Serbian). Istorijski institut SR Crne Gore u Titogradu.

- Telegraf (2018). "The building of the Marshal of the Court: Why did the communists demolish the building of Pioneer Park in 1957?". Telegraf.rs (in Serbian).

- Stephen Taylor (1935). Who's who in Central and East Europe. Central European Times Publishing Company.

- Online, Vesti (6 September 2023). "Nepravedno zapostavljeni: Ađutanti srpskih vladara (1): Arsa nije hteo nagradu". Vesti online.

- Online, Vesti (7 September 2023). "Nepravedno zapostavljeni: Ađutanti srpskih vladara (2): Sa knezom u čamcu". Vesti online.

- Online, Vesti (8 September 2023). "Nepravedno zapostavljeni: Ađutanti srpskih vladara (3): Atentat u Košutnjaku". Vesti online.

- Online, Vesti (9 September 2023). "Nepravedno zapostavljeni: Ađutanti srpskih vladara (4): Maršal dvora". Vesti online.

- Online, Vesti (11 September 2023). "Nepravedno zapostavljeni: Ađutanti srpskih vladara (5): U službi kraljeva". Vesti online.

- Radovanović, Nikolina (17 April 2021). "Enigma Pionirskog parka: Zašto je srušena zgrada Maršalata?". 011info – najbolji vodič kroz Beograd (in Serbian).