Oratorio di Santa Maria (Garbagna Novarese)

| Oratorio di Santa Maria | |

|---|---|

Front of the oratory | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic Church |

| Province | Novara |

| Region | Piedmont |

| Ownership | Municipality of Garbagna Novarese |

| Patron | Mary |

| Location | |

| Municipality | Garbagna Novarese |

| Country | Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 45°23′31″N 8°39′51″E / 45.39182°N 8.66414°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Oratory |

| Style | Romanesque and Neoclassical |

| Completed | around 1070 |

| Direction of façade | West |

Oratorio di Santa Maria (Oratory of Saint Mary), commonly known as Madonna di Campagna (Madonna of the Countryside), is a small medieval religious building located northeast of the village of Garbagna Novarese, in the province and diocese of Novara, near the Novara–Alessandria railway line.[1]

History

The construction of the building is estimated to have taken place between 1050 and 1075, particularly the apse, with subsequent modifications dating to the 12th century.[2][3][4] The first documented reference to the church dates to 1077, with a later citation in 1181.[5]

The appearance of the building has been significantly altered over the centuries, without, however, compromising its original structure or the valuable frescoes preserved inside.

A 1347 document concerning the investiture of an ecclesiastical benefice (Consignationes) records that the chaplain of the oratory was an unnamed priest from Cantù, who did not reside in the adjoining house. The oratory's lands amounted to 65 pertiche (equivalent to over four hectares), most of which were arable.[6]

In 1490, the painter Gian Antonio Merli executed a Madonna and Child in the space above the entrance, though the fresco was later lost.[7]

The building underwent renovations during the Gothic period, when the dentil arches were added — still visible today inside the adjoining house and originally also present on the north side.[1]

In the 18th century, the house adjoining the southern side of the church was inhabited by a hermit (romito), who lived by begging in both Garbagna and the surrounding areas, in accordance with the arrangements established by the episcopal curia of Novara.[8] In 1848, the same role was assigned to a certain Carlo Maria Zorzoli, whose identity remains unknown.[9]

During the cholera pandemic of 1854–1855, the building was used as a lazaretto.[9]

The façade originally featured a simple gabled profile, with a wide double-pitched eave protecting a fifteenth-century fresco of the Nursing Madonna above the door. It was remodeled in 1908[10] in the neoclassical style by architect Giovanni Lazanio, who raised the wall significantly above the nave's roof. The unusual appearance was met with criticism; emblematic are the words of architectural historian Paolo Verzone in 1936: a very high and presumptuous façade that, protruding like an isolated wall above the roofs, gives the monument a comical appearance.[11] It was later further modified, with its height reduced to the current level for structural reasons.[3][12]

During the pastoral visit on August 7, 1932, the Bishop of Novara, Giuseppe Castelli, noted the urgent need for repairs to the building. He therefore recommended notifying the podestà (the political office that replaced the mayor during the Fascist era) to intervene and, among other measures, preserve the valuable frescoes.[13]

Between the 1960s and 1970s, unknown individuals entered the building through a window of the adjoining house and stole the ancient altar along with a small marble column.[14]

Between 1994 and 2000, the municipality of Garbagna commissioned a conservation and restoration project, which encompassed the crawl space, walls, roofs, interior plaster, and frescoes. The work was coordinated by architect Maria Grazia Porzio and two local companies from Novara, under the supervision of the Superintendence for the Historical, Artistic, and Ethno-Anthropological Heritage of Piedmont.[15][2]

Exterior

Today, the building consists of a single nave, a semicircular apse, and a gabled wooden roof.[1]

The walls are primarily constructed of horizontally laid bricks bound with mortar, except on the sides and the façade, where irregular reused materials were employed.[1]

The exterior of the apse is divided into five sections by pilasters and topped with blind arches arranged in groups of three. Originally, four splayed single-lancet windows lit the interior — two in the apse and two on the southern wall. These were bricked up in the 15th century, when the interior was frescoed.[1]

The fresco above the entrance was still visible in 1980,[16] but had disappeared by 2009.[17]

Interior

The oratory houses thirteen frescoes from the 15th century, located on the semicircular apse wall and the left wall of the nave. Restoration efforts in recent years have enhanced their legibility and visual impact.

In the apse area, from left to right, we find:

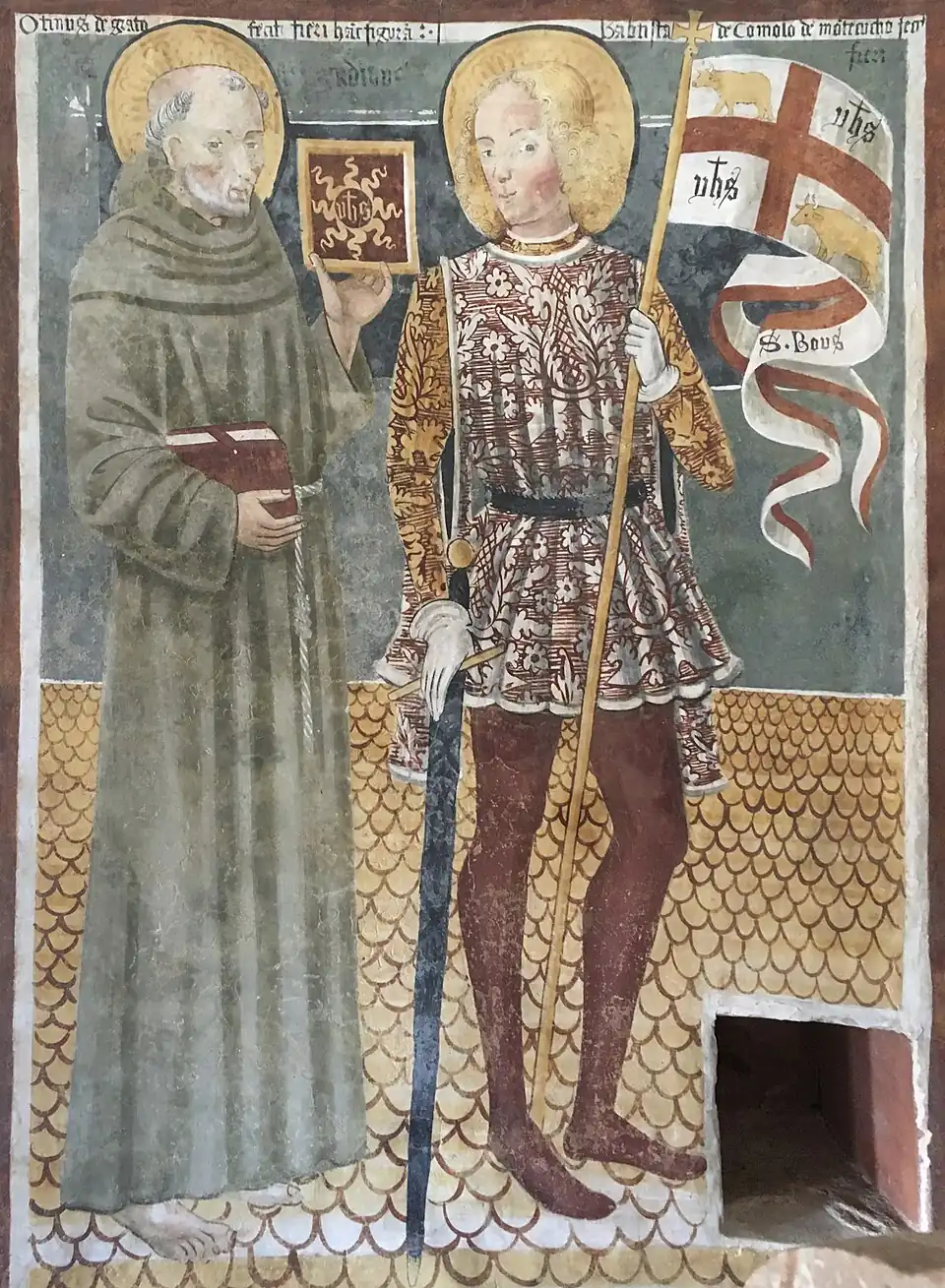

- Saint Bernardino of Siena and Saint Bobo;

- Madonna enthroned with Child, crowned by two musician angels, with Saint Francis presenting the kneeling patron; the painting dates to 1481 and is signed by Tommaso Cagnola; it is regarded as a key work for understanding Cagnola's artistic output;[1]

- in the center, a Pietà of great dramatic tension, still rich in Romanesque echoes, dating to the early 15th century;

- from the same period is a small depiction of Saint Helena, placed above a single-lancet window;

- Madonna with Child, also dating to the beginning of the 15th century;

- on the far right, the Blessed Peter Lombard and Saint Nicholas of Tolentino.

On the left wall is a long cartouche containing seven frescoes. From left to right:[18]

- Saint Gratus of Aosta;

- Madonna enthroned with naked Child;

- Vision of Saint Eustace: recognized for its historical, religious, and aesthetic value, the painting is notable for the artist’s ability to transform a scene of noble hunting life into a religious image through the miraculous appearance of a crucifix between the deer’s antlers; like other works on the same wall, it is also attributed to the Cagnola workshop;

- Saint Bernard of Aosta;

- Madonna enthroned with Child (of the shoe);

- Saint Catherine of Alexandria;

- Madonna enthroned with Child and a little friar.

Apse frescoes

| Image | Subject, location and size[19] | Critism |

|---|---|---|

|

Blessed Peter Lombard with Saint Nicholas of Tolentino | In the 15th century in the Novara area, the subject of the local Peter Lombard, known as the Master of the Sentences, often recurred.

Antonio Massara appreciated its workmanship, describing its details: a figure with a mitre adorned with pearls and an orange cope under which the beautiful folds of the alb unfold. The hands, wearing white chiroteche with rings on the fingers, hold the pastoral staff in the left, and three books and a pen in the right to demonstrate his great doctrine. A halo of golden rays surrounds his head. Massara himself, while scraping away the plaster, discovered an inscription on the fresco relating to the patronage: Stefanina de Prolis et Iacobinus eius filius fecerunt fieri hanc figuram.[20] |

| First box on the right | ||

| 176 x 105 cm | ||

|

Madonna enthroned with Child (Maestà) | The Ferros dated the work to the early 1400s, contemporary with the adjacent Saint Helena and Pietà.[21]

Bisogni and Calciolari confirm the dating, analyzing the typically late Gothic rendering of the draperies and the structure of the throne. These elements, together with the cursive rendering of the faces, suggest the attribution to the Master of Garbagna, whose known works are few but strongly characterized.[2] |

| Second box from the right | ||

| 170 x 105 cm | ||

.jpg) |

Saint John the Baptist | Fragment of a fresco that emerged during the restoration completed in 2000, which Madonna enthroned with Child (Maestà) largely overlaps. A haloed head and the bare shoulder of a male figure can be identified, whose disheveled hair suggests identification with the Baptist, whose iconography shows him dressed in a short fur coat, without sleeves. Bisogni and Calciolari appreciate the workmanship and propose a dating to the 13th century.[2] |

| Above Madonna enthroned with Child (Maestà) | ||

|

Saint Helena | The Ferros dated the work to the early 1400s, contemporary with the adjacent Pietà and Madonna enthroned with Child (Maestà).[21]

Bisogni and Calciolari confirm the dating by focusing on the typically late Gothic rendering of the draperies. The face, made in a cursive manner, describes a very pronounced nose with small eyes and mouth. The slender hands, with tapered fingers rendered with a calligraphic line, contribute to attributing this work to the Master of Garbagna, whose known works are few but strongly characterized.[2] |

| Third box from the right, above the single-light window | ||

| 50 x 50 cm | ||

|

Pietà | Antonio Massara considered this very ancient representation of the Pietà one of the first medieval attempts to represent maternal pain and the immobility of death. The rendering of the limbs, the draperies around Christ's body, the eye-shaped navel and the flagella hanging from the cross still follow the canons of the Byzantine schools (an improper term usually referring to ancient representations with rigid and symbolic expressions). The rendering of anguish stands out instead as a new element, an element that cannot be learned in the training of artists and to which the wise study of the realistic forms of the following centuries would have added nothing.[22]

In addition to confirming its artistic relevance, Lino Cassani added that the painting had always been the object of great popular devotion.[12] The Ferros considered it a rare example of a work from the early 1400s, not excluding that it could be even older, noting strong Romanesque characteristics in it.[23] Bisogni and Calciolari confirm the dating considering the purely late Gothic rendering of the draperies, which, together with the cursive execution of the faces, suggest the attribution to the Master of Garbagna, whose known works are few but strongly characterised.[2] |

| Fourth box from the right | ||

| 173 x 110 cm | ||

|

Madonna with the patron and Saint Francis | Antonio Massara saw in this work a timid prelude to the Renaissance, in which art moved away from canonical symbolism and moved closer to man, representing his earthly affections and feelings: medieval mysticism filled the dark sky with ghosts that now, at the first rays of the rising sun, take on the vaguest forms of nature.

Massara also underlined how in this work the author was explicitly indicated for the first time, next to the name of the patron on a clearly visible cartouche: Tommaso Cagnola. Previously, the authors did not sign their works, only some timid hints had appeared on the edges of the paintings in the 15th century. Like Cagnola, the artists of the following years, aware of their work, would begin to sign numerous works, mostly on cartouches next to the names of the patrons. This work also accurately reports the date of execution: 27 April 1481.[20] |

| Fifth box from the right | ||

| 173 x 193 cm | ||

|

Saint Bernardino of Siena with Saint Bobo |

For Dominique Rigaux, the figure of St. Bovo harks back to the tradition of military saints, dear to the Longobard religion: the model is a young knight, with blond hair flowing down his shoulders, elegantly dressed. This model was widespread in the peasant culture of the Po Valley and the pre-Alpine valleys, a culture that appreciated the images typical of the International Gothic and of the chansons de geste. The figure resembles the other knightly saints venerated in the region (Martin, Maurice and Domninus) and embodies the image of the miles Christi, defender of the poor and oppressed, whose insignia he bears: the white banner with a red cross, emblem of the Christian armies during the crusades.[24] |

| Sixth box from the right | ||

| 173 x 121 cm |

Left wall frescoes

| Image | Subject, location and size[19] | Criticism |

|---|---|---|

|

Madonna enthroned with Child and a little friar | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, estimating its creation in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481. In it Massara observed characteristics common to two other works on the same wall: the Madonna enthroned with Child (of the shoe) and the Madonna enthroned with naked Child.[25]

Examining the inscription Alaxina uxor Baltramini fecit fieri, the critic proposed that the work was an ex-voto through which Alaxina implored the Madonna for a grace in favor of her little son, portrayed kneeling in the clothes of a little friar.[25] |

| First box on the right | ||

| 170 x 70 cm | ||

|

Saint Catherine of Alexandria | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, who created it in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481.[25] |

| Second box from the right | ||

| 170 x 65 cm | ||

_-_Oratorio_di_Santa_Maria_-_Garbagna_Novarese.jpg) |

Madonna enthroned with Child (of the shoe) | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, who created it in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481.[25] |

| Third box from the right | ||

| 170 x 70 cm | ||

|

Saint Bernard of Aosta | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, who created it in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481. The critic simply defined the work as a rigid figure.[25] |

| Fourth box from the right | ||

| 170 x 63 cm | ||

|

Vision of Saint Eustace | Massara praised this work, describing the scene in detail and extolling how the gentle page with the red cape and the brocade jacket who has picked up the spear, forms with his agile body between the two intelligent animals a group full of life and grace. Even though the chiaroscuro rendering and the perspective element are missing, the expressiveness and majesty of the animals represented here would never have been achieved in the works of more technically prepared artists, such as Gaudenzio Ferrari: the horse has a nobility of line that recalls the friezes of the Parthenon.[20] In the representative realism of humans and animals in this work, Massara glimpsed the first attempt of art to free itself from the subservience to religion that had characterized it until then.[25]

Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, who created it in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481.[25] |

| Fifth box from the right | ||

| 170 x 180 cm | ||

|

Madonna enthroned with naked Child | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, estimating its creation in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481.[25] |

| Sixth box from the right | ||

| 170 x 66 cm | ||

|

Saint Gratus of Aosta | Massara attributed the work to Tommaso Cagnola, estimating its creation in the same years as the Madonna with patron and Saint Francis, around 1481. Disregarding the inscription in the upper frame, the critic mistakenly believed the subject to be Saint Gaudentius.[25] |

| Seventh box from the right | ||

| 170 x 65 cm |

Turism

It is one of the stages of Cascina Baraggiolo itineraries, as part of Vie verdi del riso (Green Roads of Rice) theme,[26] and Novara e provincia - Una finestra sul territorio (Novara and province - A window on the territory), on section La Pianura del Riso (The Plain of Rice).[27] Furthermore it is reported by Itinerari d'arte nel Novarese (Art itineraries in Novarese).[28]

In literature

The writer Dante Graziosi mentions the frescoes of the Oratorio di Santa Maria in his work La terra degli aironi (The land of herons), in a passage from the chapter Gli studenti di campagna (Country students), which is dedicated to the art of ancient religious buildings scattered across the Bassa Novarese. Alongside the oratory, he cites the church of Sologno (a hamlet of Caltignaga), the oratory of Gionzana (a hamlet of Novara), the parish church of Vespolate, and the abbey of San Nazzaro Sesia. This art, preserved in these timeless places, centuries ago helped to strengthen the faith of the poor and, at the same time, reaffirm the authority of the wealthy patron families.[29]

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Chiesa della Madonna di Campagna (Oratorio di Santa Maria)" [Church of Madonna of the Countryside (Oratory of Saint Mary)]. Comune di Garbagna Novarese (in Italian). Retrieved September 16, 2021 (the website reports information from: Assessorato al Turismo (1991). Guida Turistica e Atlante Stradale Provincia di Novara [Tourist guide and road atlas of the Province of Novara]. Novara and Domodossola: Legenda).

- ^ a b c d e f Bisogni & Calciolari 2006, pp. 216–217.

- ^ a b Franzosi 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Verzone, Paolo (1932). "Conclusione". L'architettura romanica nel Novarese [Romanesque architecture in the Novara area] (in Italian). Novara: Stab. tip. E. Cattaneo. p. 25. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Gavazzoli Tomea, Maria Laura, ed. (1980). "Edifici di culto nell'XI e XII secolo. La pianura e la città". Novara e la sua terra nei secoli XI e XII: storia documenti architettura [Novara and its land in the 11th and 12th centuries: History – Documents – Architecture] (in Italian). Milan: Silvana Editoriale. pp. 36–38.

- ^ Cassani & Colli 1948, pp. 51–52, La consegna dei beni ecclesiastici di Garbagna nel 1347.

- ^ Morbio, Carlo (1841). Storia della città e diocesi di Novara [History of the city and diocese of Novara] (in Italian). Milan: Società tipografica de' classici italiani. p. 198. Retrieved October 29, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ Cassani & Colli 1948, p. 100, Gli oratori.

- ^ a b Cassani & Colli 1948, pp. 144–146, Curiosità d'archivio comunale.

- ^ Although this date is cited in the sources, it is not compatible with the birth year of the architect Giovanni Lazanio, who was only eight years old at the time.

- ^ Verzone, Paolo (1936). "Garbagna - S. Maria". R. Deputazione di Storia Patria - Bollettino per la Sezione di Novara (in Italian) (3). Novara: E. Cattaneo: 61–62. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Cassani & Colli 1948, pp. 60–63, La Madonna di Campagna.

- ^ Castelli, Giuseppe (August 7, 1932). "Decreti del Vescovo Castelli - Garbagna" [Decrees of Bishop Castelli – Garbagna]. Archivio Storico Diocesano di Novara (in Italian). Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Colli, Ernesto (1978). "Garbagna Novarese". Garbagna, Nibbiola, Vespolate, Borgolavezzaro - Le mie memorie: Gravellona Lomellina, Mergozzo, Nibbiola [Garbagna, Nibbiola, Vespolate, Borgolavezzaro - My memories: Gravellona Lomellina, Mergozzo, Nibbiola] (in Italian). Novara: Tip. San Gaudenzio. p. 21. Retrieved July 17, 2021 – via Foto Emilio Alzati.

- ^ Porzio, Maria Grazia (January 1, 2014). "Curriculum vitae di Maria Grazia Porzio" [Maria Grazia Porzio's curriculum vitae]. Comune di Recetto (in Italian). p. 3. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Edgardo Ferrari, ed. (1980). "Garbagna Novarese". Novara - 165 comuni [Novara - 165 municipalities] (in Italian). illustrated by Otello Cerri (3 ed.). Novara: Camera di Commercio Industria Artigianato e Agricoltura. p. 124.

- ^ Vecchi, Alessandro (June 23, 2010). "File:Garbagna SantaMaria.jpg". Wikimedia (in Italian). Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ Franzosi 1986a, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Franzosi 1986a, Gli affreschi.

- ^ a b c Massara 1906b, pp. 181–184.

- ^ a b Ferro & Ferro 1972, pp. 28–30, Garbagna.

- ^ Massara 1906a, p. 172.

- ^ Ferro & Ferro 1972, p. 10, Invito ad un dialetto pittorico.

- ^ Rigaux, Dominique (1997). Par la grâce du pinceau. Canonisation et image aux derniers siècles du Moyen Age. Santità, culti, agiografia: temi e prospettive - Primo Convegno di studio dell'Associazione italiana per lo studio della santità, dei culti e dell'agiografia - Roma - 24-26 ottobre 1996 (in French). Sofia Boesch Gajano (a cura di). Roma: Viella. p. 279. Retrieved July 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Massara 1904, pp. 6–7, Introduzione.

- ^ "Baraggiolo - ATL Novara - Itinerari". Agenzia Turistica Locale della Provincia di Novara (in Italian). Retrieved September 10, 2021.

- ^ Agenzia Turistica Locale della Provincia di Novara (2019). "Novara e provincia - Una finestra sul territorio". ISSUU (in Italian). p. 15. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Garbagna Novarese - Oratorio di Santa Maria". Alla scoperta di antichi Oratori Campestri... La Dolceterra - Itinerari d'arte nel Novarese (in Italian). Novara: Agenzia turistica locale della Provincia di Novara. 2009. p. 32. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Graziosi, Dante (2007). "Gli studenti di campagna". La terra degli aironi. Biblioteca del Piemonte Orientale (in Italian). Novara: Interlinea. ISBN 978-88-821-2595-0.

Bibliography

- Massara, Antonio (1904). L'iconografia di Maria Vergine nell'arte novarese [The iconography of the Virgin Mary in Novara art] (in Italian). Novara: Stab. tip. f.lli Miglio. Retrieved July 6, 2022 – via Internet archive.

- Massara, Antonio (1906a). "I primordii dell'arte novarese (parte 1)" [The beginnings of Novara art (part 1)]. Rassegna d'Arte (in Italian) (11). Milan: Menotti Bassani & C.: 170–173. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- Massara, Antonio (1906b). "I primordii dell'arte novarese (parte 2)" [The beginnings of Novara art (part 2)]. Rassegna d'Arte (in Italian) (12). Milan: Menotti Bassani & C.: 181–186. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- Cassani, Lino; Colli, Ernesto (1948). Memorie storiche di Garbagna Novarese [Historical memories of Garbagna Novarese] (in Italian). Novara: Tip. Pietro Riva & C. Retrieved July 17, 2021 – via Foto Emilio Alzati.

- Ferro, Giovan Battista; Ferro, Filippo Maria (1972). Affreschi novaresi del Quattrocento [Novara frescoes from the 15th century]. L'arte nel Novarese (in Italian). Novara: Società Storica Novarese.

- Franzosi, Franca (1986a). Un episodio della cultura figurativa novarese: Santa Maria di Garbagna e i suoi affreschi quattrocenteschi [An episode of Novara figurative culture: Santa Maria of Garbagna and its fifteenth‑century frescoes] (Thesis) (in Italian). Maria Luisa Gatti Perer and Franco Mazzini (supervisors). Milan: Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore di Milano.

- Franzosi, Franca (1986b). "Un episodio della cultura figurativa novarese: S. Maria di Garbagna e i suoi affreschi quattrocenteschi" [An episode of Novara figurative culture: Santa Maria of Garbagna and its fifteenth‑century frescoes] (PDF). Società Storica Novarese - Segnalazioni di tesi di laurea (in Italian). pp. 6–12. Retrieved May 8, 2025.

- Franzosi, Franca (2001). "L'oratorio di Santa Maria de Agris a Garbagna Novarese" [The oratory of Santa Maria de Agris in Garbagna Novarese]. In Gian Piero Colombo (ed.). Segni e tracce di architettura romanica nel Novarese. Rilievi e immagini [Signs and traces of Romanesque architecture in the Novara area. Surveys and images]. I segni (in Italian). Novara: Interlinea. ISBN 88-8212-319-7. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- Bisogni, Fabio; Calciolari, Chiara, eds. (2006). "Garbagna - Santa Maria". Affreschi novaresi del Trecento e del Quattrocento: arte, devozione e società [Novara frescoes from the 14th and 15th centuries: art, devotion, and society] (in Italian). Cinisello Balsamo: Silvana. ISBN 978-8-83-660651-1. Retrieved January 29, 2024 – via Academia.

External links

- Image gallery and virtual tour on Foto Emilio Alzati

- Image gallery on Chiese Romaniche e Gotiche del Piemonte

See also

- Chiesa di San Michele Arcangelo (Garbagna Novarese)

- History of Garbagna Novarese

- Garbagna Novarese farmsteads, whose owners commissioned some frescos of Santa Maria, during Middle Ages