Shubenacadie, Nova Scotia

Shubenacadie | |

|---|---|

| |

Shubenacadie Location in Nova Scotia | |

| Coordinates: 45°8′23.58″N 63°25′3.17″W / 45.1398833°N 63.4175472°W | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| County | Hants County |

| Municipality | East Hants Municipality |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-3 (ADT) |

| Canadian Postal Code | B0N |

| Area code | 902 |

| Telephone Exchange | 883 |

| NTS Map | 011E03 |

| GNBC Code | CBIQT |

Shubenacadie (/ˌʃuːbəˈnækədi/ SHOO-bə-NAK-ə-dee) is an unincorporated community in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located in East Hants Municipality in Hants County.[1][2] As of 2021, the population was 411.

The name from which "Shubenacadie" derives is the Mi'kmaq name for the area, "Sipekne'katik", meaning "place abounding in groundnuts", or "place where the wapato grows."[3][4] Historically, the Sipekne'katik region was a large stretch of territory that covered central Nova Scotia.

History

Settlement

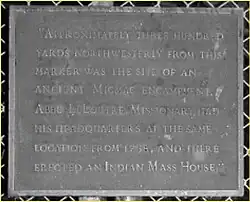

Father Louis-Pierre Thury sought to gather the Mi'kmaq of Peninsular Nova Scotia into a single settlement around Shubenacadie as early as 1699. Not until the Dummer's War between the New France-aligned Wabanaki Confederacy and English New England from 1722–1725, however, did Antoine Gaulin,[5] a Quebec-born missionary, erect a permanent mission at Shubenacadie (adjacent to Snides Lake and close to the former Residential school). He also made seasonal trips to Cape Sable, LaHave, and Mirlegueche.[6]

In 1738, Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre arrived in October of that year at Mission Sainte-Anne, having spent the previous winter in Cape Breton learning the Mi'kmaq language with Abbé Pierre Maillard. During Dummer's War and King George's War, Mission Sainte-Anne was a military base as well as a place of worship. The army of Louis Coulon de Villiers passed this way on their march toward the Battle of Grand Pré in 1747, and Mi'kmaq warriors used the site as a staging point for their attacks on Halifax and Dartmouth during Father Le Loutre's War.[6]

1932 bank robbery

On 23 August 1932, a botched robbery attempt targeted the Royal Bank of Canada branch in Shubenacadie. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), who had recently replaced the Nova Scotia Police as the provincial police force, were alerted of the plan by Edson Boutilier, one of the robbers. The police provided Boutilier with an unloaded gun and a car and attempted to ambush the robbers, resulting in a shootout that left Boutilier wounded and his brother-in-law Gerald Freckleton dead.[7] The incident sparked significant public criticism of the RCMP's armed presence in the Nova Scotia.[8]

Residential school

Shubenacadie was the location of the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School, a Canadian residential school, that was operated from 1923 to 1967.[9]: 357 Over 1,000 children are estimated to have been placed in the institution over 37 years.[10] The school building was destroyed by fire in 1986. The school's site is now occupied by a plastics factory, although a few staff houses remain and the road to the school is still named "Indian School Road".[11]

Nora Bernard, a Mi'kmaq activist, attended the school for five years. Later in life, she was directly responsible for what became the largest class action lawsuit in Canadian history, compensation for an estimated 79,000 former students of the Canadian Indian residential school system.[12][13] The former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School was designated a national historic site in July 2020.[14]

Demographics

Shubenacadie part A

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Shubenacadie part A had a population of 401 living in 176 of its 191 total private dwellings, a change of -45.4% from its 2016 population of 735. With a land area of 4 km2 (1.5 sq mi), it had a population density of 100.3/km2 (259.6/sq mi) in 2021.[15]

Shubenacadie part B

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Shubenacadie part B had a population of 10 living in 6 of its 7 total private dwellings, a change of -94.7% from its 2016 population of 187. With a land area of 2.12 km2 (0.82 sq mi), it had a population density of 4.7/km2 (12.2/sq mi) in 2021.[15]

Shubenacadie Tree

The Shubenacadie Tree was a 300-year-old red oak tree located near the community of Shubenacadie,[16] destroyed during Hurricane Fiona in 2022.[17][18] The tree has been referred to as the "most photographed tree in Nova Scotia".[19] After the tree fell, a resident gathered its acorns and grew a total of 24 seedlings with plans to share them with the community.[19][20] Some wood from the fallen tree was used to make Christmas ornaments and coasters by a local craftsman, who sold them and donated part of the proceeds to disaster relief for the hurricane.[21] Halifax newspaper The Coast published a eulogy for the tree.[22]

Notable residents

- Anna Mae Aquash – a Mi'kmaq activist

- Daniel N. Paul – a Mi'kmaq elder, author, and activist

- Jean-Baptiste Cope – a leader of Mi'kmaq militia

- Jean-Louis Le Loutre – a missionary priest

- Shubenacadie Sam – a groundhog at the Shubenacadie Wildlife Park that gives predictions on Groundhog Day.

- George Lang – a stonemason who built the Halifax Court House and other buildings

See also

References

- ^ "Nova Scotia GeoNAMES". NovaScotia.ca. Nova Scotia Government. Retrieved 2025-01-29.

- ^ "Canadian Geographical Names Database". nrcan.gc.ca. Government of Canada. Retrieved 2025-01-29.

- ^ Sable, Trudy; Francis, Bernard; Lewis, Roger J. (2012). The Language of this Land, Mi'kma'ki. Cape Breton University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-897009-49-9.

- ^ Gesner, Abraham (1849). The industrial resources of Nova Scotia. Comprehending the physical geography, topography, geology, agriculture, fisheries, mines, forests . Harvard University. Halifax, N.S. A. & W. MacKinlay.

- ^ "GAULIN, ANTOINE". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ a b Northeast Archaeological Research Archived 2012-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bousquet, Tim (15 February 2025). "Part 1: 'A coupla suckers'". Halifax Examiner. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ Bousquet, Tim (22 February 2025). "Part 2: Blind Pig". Halifax Examiner. Retrieved 19 August 2025.

- ^ Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future : summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (PDF). [Winnipeg, Manitoba]: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. ISBN 978-0-660-02078-5. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Contemporary Mi'kmaq – Kiskukewaq Mi'kmaq". Cape Breton University. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ "Survivors of residential school system gather in N.S. to hear apology - Living - The Guardian". www.theguardian.pe.ca. Archived from the original on 2016-06-16. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ Halifax Daily News article on Bernard in 2006 Archived 2008-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Archived at Arnold Pizzo McKiggan

- ^ "Foul play suspected in death". Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

- ^ "Former Shubenacadie Indian Residential School National Historic Site". parks.canada.ca. 2023-09-20. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ a b "Population and dwelling counts: Canada and designated places". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved May 9, 2022.

- ^ Renić, Karla (26 September 2022). "Nova Scotia mourns loss of iconic 300-year-old tree, fallen to Fiona's fury". Global News. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ "Iconic Shubenacadie Tree felled by Fiona". CityNews. Halifax. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Davenport, Ruth (26 September 2022). "'It's a constant in our lives': Nova Scotians mourn iconic tree felled by Fiona". CBC News. Nova Scotia: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ a b Petracek, Heidi (10 July 2023). "Why one woman is growing 'legacy' acorns from Nova Scotia's fallen 'Shubenacadie tree'". CTV News. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Elliott, Wendy (14 August 2024). "A tree carries 'history in its genetics'". PNI Atlantic News. Halifax: Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on 20 August 2025. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Welland, Victoria (28 December 2022). "How a piece of an iconic N.S. tree brought down by Fiona became Christmas ornaments". CBC News. Nova Scotia: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Mullin, Morgan (28 September 2022). "A eulogy for The Shubie Tree" (PDF). The Coast. Halifax. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

Further reading

- Fergusson, C. Bruce (1967). Place-Names and Places of Nova Scotia. Halifax, NS: Public Archives of Nova Scotia. p. 622-623. Retrieved 14 July 2025.