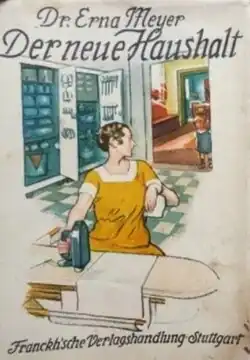

The New Household

| |

| Author | Erna Meyer |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der neue Haushalt |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Household guidebook |

| Publisher | Franckh'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung |

Publication date | 1926 |

| Publication place | Stuttgart, Germany |

Der neue Haushalt – Ein Wegweiser zu wirtschaftlicher Hausführung (transl. The new household – A guide to economical housekeeping) is a 1926 household guidebook by German home economist Erna Meyer. The book promotes a systematic, professional approach to housework as a means of both personal development and social progress. Drawing on earlier reform ideas, Meyer frames the household as a key economic unit and the housewife as an active agent in modernizing society. While reinforcing traditional gender roles, she calls for the rationalization of domestic labor and linked it to education, efficiency, and technological advancement. The book gained wide influence, with dozens of editions and international reach.

Content

In writing The New Household, Meyer was strongly influenced by Christine Frederick's 1913 book The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management.[1] In The New Household, Meyer introduces her audience to a deliberate and structured reorganization of domestic life, drawing on the reform pedagogical methods of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and Maria Montessori. For her, rationalizing household management was not just a private matter but a far-reaching endeavor meant to transform all areas of life and ultimately reshape society.[2] She lays out an all-encompassing framework for household management, covering everything from budgeting and cooking to cleaning, furnishing, and childrearing.[3]

Meyer did not challenge the broader social division of labor between the sexes. Instead, her goal is to elevate housework to the status of serious professional labor. She explicitly frames her project as an effort to establish housewifery as "the most serious professional work" and thereby promote its professionalization.[2] She seeks to reverse the view of housework as "unproductive" by equating the kitchen with the factory—calling it "the smallest factory in the world"—in order to promote ideological recognition of housewives' labor.[4]

Meyer argues that the housewife must acquire the skills to manage the household according to home economics principles, treating it as a kind of enterprise. At the heart of the book lies the concept of "realizing the economic principle in the household", which she models after what she calls the "household of nature". Nature, in her view, provides the ideal example for a broad rationalization and reorganization of society. Within this framework of "natural rationality", Meyer conceives of the household as the smallest economic entity and the true "nucleus" of a sweeping societal modernization. In The New Household, the modern housewife is not solely committed to her family's wellbeing but also actively contributes to the daily renewal of the collective.[2]

In The New Household, the woman is no longer a slave to her duties but their "creative master".[4] Meyer links the housework to the expanding, though in the 1920s Germany still prohibitively expensive, electrification of the home.[3] Realizing such a transformation, however, requires more than modern housing—it demands a fundamental reorientation within the woman herself, one that depended on proper education. Meyer articulates this in ten guiding principles, extending even to matters such as "correct posture" and "methodically conducted physical exercise". Meyer argues that emotional disturbances such as hysteria or irritability are signs of an "unsatisfied domestic need", symptoms of a workplace that lacked proper organization.[4]

Reception

The New Household became a bestseller.[4] Within two years it went through 29 editions[5] and eventually went through more than 40. As one of the most influential household manuals of the interwar period, its reach extended well beyond the borders of Germany.[2] It was translated and soon followed by household management studies in the Netherlands, Finland, United Kingdom, France, and Italy.[5]

See also

- How to Cook in Palestine–1936 book by Meyer

References

- ^ Mezei, Kathy; Briganti, Chiara (1 January 2012). The Domestic Space Reader. University of Toronto Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8020-9664-7. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d Müller, Ann-Kathrin (6 May 2024). ""What shall I cook?" Erna Meyer's WIZO-Cookbook in the field of tension between Nation building and shared cultural heritage". Cultural Heritage Studies. Vol. 7. Bielefeld, Germany: Verlag. pp. 174–175. doi:10.14361/9783839466995-010. ISBN 978-3-8376-6699-1. ISSN 2752-1516.

- ^ a b Ward, Janet (4 April 2001). Weimar Surfaces: Urban Visual Culture in 1920s Germany. Univ of California Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-520-42065-6. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ a b c d Spechtenhauser, Klaus (9 December 2005). The Kitchen: Life World, Usage, Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 29. ISBN 978-3-7643-7281-1. Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Alexandra (2010). Modern Women: Women Artists at The Museum of Modern Art. The Museum of Modern Art. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-87070-660-8. Retrieved 25 July 2025.