Timeline of Brussels

| History of Belgium |

|---|

|

|

Timeline • Military • Jewish history • LGBT |

The following is a timeline of the history of Brussels, Belgium.

Prehistory

- 10,000–2600 BCE – Polished silex from the Mesolithic era are located in the Nekkersgat.[1]

- 5th–1st century BCE – A settlement from the La Tène culture is located on the Champ Saint-Anne/Sint-Annaveld in Anderlecht.[2]

- 3000–2200 BCE – Settlements from the Michelsberg culture are located in the Sonian Forest.[2][3]

- 1000–800 BCE – Celtic tribes settle in what is now Brussels.[4]

Roman Period

.jpg)

- A fairly important Roman settlement is in existence in Stalle.[1]

- 175 CE – A Roman villa is in existence in Laeken.[4]

- 2nd century CE – A Gallo-Roman villa is constructed in Jette, located in today's King Baudouin Park.[5]

- 2nd–3rd century CE – A Roman villa is built on a former Neolithic settlement in Anderlecht, near the present-day Allée de la Villa Romaine/Romeinse-Villadreef.[2][6]

Middle Ages

- 4th–6th centuries CE

- 500–700: A Merovingian cemetery containing over three hundred graves is located on the Champ Saint-Anne/Sint-Annaveld.[2]

- 580 – Saint Gaugericus builds a chapel on an island in the river Senne, laying the origin of the settlement which is to become Brussels.[7]

- c. 640 – Saint Alena dies in Forest.[8]

- 843 – 10 August: The region becomes part of Lotharingia after the signing of the Treaty of Verdun.[4]

- 870 – First mention of the County of Brussels is made in the Treaty of Meerssen.

- 959 – The city becomes part of Lower Lotharingia.[4]

- 977–979 – A castrum is constructed on Saint-Géry/Sint-Goriks Island.[4]

- 979 – Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine, transfers the relics of Saint Gudula to the chapel built by Saint Gaugericus, marking the city's official founding.

- 1001 – Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine, becomes Count of Brussels.[4]

- 1012 – Saint Guy dies in Anderlecht on his return home from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.[9]

- 1015–1020 – Oldest written record of the city is made by Olbert of Gembloux.[10]

- 1041–1047 – The Palace of Coudenberg begins construction.[4]

- 1047 – The relics of Saint Gudula are transferred from the Church of St. Gaugericus to the Church of St. Michael by Lambert II, Count of Leuven.[4][11]

- 1063–1100 – The city's first fortifications are built.

- 1076–1078 – Lady Renilde, widow of Folcard, Lord of Anderlecht, establishes a chapter in Anderlecht and brings over the relics of Saint Guy.[11]

- 1095

- Dieleghem Abbey is first attested.

- The Castellany of Brussels is first recorded, possibly founded by Steppo de Brosele.

- 1105 – Forest Abbey is founded.

- 1125 – The Amman of Brussels is first attested.[4]

- 1129 – The Lindekemale Mill is first attested.

- 1135 – The city's seal is first attested, depicting the Archangel Michael robed, with outstretched wings, a halo, and the Latin inscription Sigillum Sancti Michaëlis.[12]

- 1142 or 1147 – The Battle of Ransbeek takes place.

- 1150 – St. Peter's Hospital is established as a leper colony, run by a community of lay brothers and sisters, outside the city's walls.[13]

- 1152 – St. Nicholas' Church is first attested.[12]

- 1174 – The Grand-Place/Grote Markt is first attested as the Forum inferior or Nedermerckt.[14]

- 1183 – The Duchy of Brabant is formed after the merger of the Counties of Brussels and Leuven and the Landgraviate of Brabant.

- 1187–1260 – Gerard of Brussels, a geometer and philosopher, authors Liber de motu.

- 1190 – Richard I of England passes through the city.[4]

- 1195 – St. John's Clinic is established.

- 1196 – La Cambre Abbey is founded by Benedictine noble Gisèle.

- 1209 – The Lordship of Carloo is first attested.[1]

- 1213

- 1225 – The current Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula begins construction.[4][17]

- 1228 – Duke Henry the Courageous designates the Het Heideken area as common land.[18]

- 1229

- 1250

- The Great Beguinage of Brussels is formalised by Duke John the Victorious.[21]

- 11 June: Saint Alice dies in isolation from leprosy at La Cambre Abbey.[22]

- 1252 – The Beguinage of Anderlecht is founded.

- 1253 – Karreveld Castle is first attested.

- 1258 – The Convent of Boetendael is first attested.[1]

- 1262 – The Priory of Val-Duchesse is established by Adelaide of Burgundy, Duchess of Brabant.

- 1265 – 19 February: Saint Boniface dies at La Cambre Abbey.[23]

- 1267 – Duke John the Victorious relocates the capital of the Duchy of Brabant from Leuven to the city.

- 1270 – First mention of the ducal Hunting Lodge of Boitsfort is made.[24]

- c. 1274 – Beghards first appear in the city.[25]

- 1282 – First mention of the Drapery Court and the Wise Council is made.[4]

- 1289 – The cloth guild is officially recognised by Duke John the Victorious.[26]

- 1290

- Duke John the Victorious bans artisans from forming associations without prior approval from the aldermen and the amman.[27]

- 18 June: The hermit Mary the Miserable is buried alive for theft and witchcraft, with a chapel later built on her burial site.

- 1292 – Duke John the Victorious grants the city the right to collect taxes on crane use at the quay and on city gates rentes.[4][19]

- 1295

- Duke John the Peaceful authorises aldermen to collect duty on beer as a town revenue.[4]

- Meulebeek (present-day Molenbeek-Saint-Jean) is part of the Coop of Brussels.[28]

- 1296 – 14 February: Obbrussel becomes part of the Coop.[4]

- 1301 – Schaerbeek becomes part of the Coop.[4]

- 1303 – 6 May: Following a rebellion sparked by patriciate efforts to join the Drapery Court, Duke John the Peaceful grants them the right through a formal privilege, marking the beginning of the Brussels Revolt.[4][27]

- 1304 – The Church of Our Lady of Victories at the Sablon is founded.[29]

- 1305 – Walter the Wild is killed by his cousin Joris van der Noot for their shared love for Goedele van der Zennen, and later lends his name to the Rue du Bois Sauvage/Wildewoudstraat.[30]

- 1306

- 1 February: A quarrel between a commoner and a patrician sparks a riot and defies ducal authority.[27]

- Early February: Craftsmen draft a new constitution, but Duke John the Peaceful refuses to recognise it.[27]

- Mid-February: Duke John the Peaceful sides with the patricians, declaring virtual war on the craftsmen.[27]

- 19 March: The Guilds of Saint Luke and Four Crowned are first attested.

- 1 May: The craftsmen are defeated in battle.[27]

- 12 June: The Seven Noble Houses of Brussels are first attested when Duke John the Peaceful authorises the magistrates to suppress unrest, disarming craftsmen, prohibiting guild meetings, and restoring the city government with seven aldermen chosen by the Noble Houses.[4][27][31]

- 1308 – The Meyboom is first attested.[32]

- 1312 – Etterbeek becomes part of the Coop.[33]

- 1315–1317 – The Great Famine ravages the region.

- 1316 – A plague epidemic strikes the city's population.[12]

- 1318 – John of Ruusbroec becomes a parish priest at the Church of St. Michael and St. Gudula together with his uncle Jan Hinckaert.

- 1320 – A horse market is first held on the Grand Sablon/Grote Zavel, continuing until 1754.[12][34]

- 1321 – Dry Borren is first attested as a hermitage.

- 1328

- 1331 – Laeken becomes part of the Coop.[4]

- 1334 – The city sets up a financial structure with two treasurers overseeing accounts.[19]

- 1335 – 23 August: The Christian mystic Heilwige Bloemardinne, considered the city's first feminist, dies.[37]

- 1341 – An ordinance forbids defecation and urination in the streets under penalty of a fine, but it is widely ignored.[38]

- 1342 – The city bans the construction of thatched roofs to prevent fires.[39]

- 1344 – Willem van Duvenvoorde receives permission from the Diocese of Cambrai to add the Nassau Chapel to the Inn of the Lek.[40]

- 1348 – The Ommegang begins as a Marian procession.[41]

- 1349

- 1353 – The city council decides to build a cloth hall to complement the Bread Hall and the Meat Hall.[12]

- 1356

- The Joyous Entry of Joanna and Wenceslaus into the city takes place.

- 17 August: Battle of Scheut: Louis II, Count of Flanders defeats Joanna, Duchess of Brabant, who then besieges the city.

- 24 October: The city is liberated by group of Brabantian patriots led by Everard 't Serclaes, Lord of Kruikenburg.[4]

- The expansion of the city's fortifications begins.

- 1360 – 22 July: A revolt occurs, inspired by Pieter Couterel's revolt in Leuven, as craftsmen take up arms and burn the Steenpoort, but the rebels are soon defeated by patricians, and stringent penal laws are enacted.[43]

- 1365 – The Brewers' Guild is recognised.[44][45]

- 1367 – Rouge Cloître Abbey is founded.[4]

- 1368

- Jan Collaey donates land near the Droge Heergracht to the Alexians, on what is now the Rue des Alexiens/Cellebroedersstraat.[46]

- Moderate patricians begin implementing measures to grant the bourgeois greater participatory rights in the city government, as discontent and revolution continue to threaten.

- 1370 – 22 May: The Sacrament of Miracle occurs, killing 6–20, followed by the expulsion of the city's remaining Jewish population.

- 1375 – 19 June: A ducal act requires all married or widowed men aged 28 or older to register in the city's books and designate affiliation with a specific Noble House.[47]

- 1380 – Geert Pipenpoy becomes the city's first mayor.

- 1381 – The Grand Royal Oath of St. George of the Crossbowmen of Brussels and the Royal Grand Oath of the Archers of St. Sebastian are established by the Duchess of Brabant.[48][49][50][16]

- 1382 – After unrest in Leuven, hundreds of merchants and thousands of skilled craftsmen migrate to the city in one of its earliest large-scale migrations.[51]

- 1383 – The original Halle Gate is built.

- 1388

- 26 March: A military expedition heads to Gaasbeek Castle after Everard t'Serclaes, on his way from Ternat to the city, is mutilated by order of Sweder of Abcoude.[52]

- 31 March: Everard t'Serclaes dies at the L'Étoile/De Sterre guildhall on the Grand-Place.[52]

- 1394 – Anderlecht and Forest become part of the Coop.[4]

.jpg)

- 1400 – Population: c. 20,000.[4]

- 1401 – The Town Hall begins construction on the Grand-Place.

- 1402 – The Sacrament of Miracle is recognised by the church.[12]

- 1404 – 1 July: The Court of Auditors of Brussels is established by Anthony, Duke of Brabant.

- 1405 – A fire ravages the city.[53]

- 1406

- 14 April: A fire destroys part of the Church of Our Lady of the Chapel and the surrounding neighbourhood.[39]

- 18 December: The Joyous Entry of Anthony the Great Bastard into the city takes place.[4][54]

- 1407 – A fire brigade, made up of craft guild members and locals, is in existence, though water is often in shortage despite a water service.[53]

- 1411 – 12 June: The Homines Intelligentiae are first mentioned in an ecclesiastical ruling by Pierre d'Ailly, and are prosecuted, resulting in the imprisonment and exile of their leader William of Hildernissen.

- 1420

- 5 February: Den Boeck chamber of rhetoric is recognised by John IV, Duke of Brabant.

- 30 September: Duke John IV flees the city after the States of Brabant appointed Philip of Saint Pol as ruwaard.[55]

- 1421

- 21 January: Duke John IV retakes the city with an army composed largely of German knights.[55]

- 27 January: The guilds occupy the Grand-Place and crowds demonstrate before the Coudenberg Palace in support of Philip of Saint Pol.[55]

- 29 January: The former Amman Jan Clutinc is decapitated, ducal household members arrested, and pro-John aldermen imprisoned or flee.[55]

- 11 February: The guilds, organised into the Nine Nations, join the Seven Noble Houses in city governance as part of democratic reforms.[55][56]

- 11 October: Duke John IV returns to the city.

- 1422 – The Brethren of the Common Life settle in the city.

- 1424 – The city's aldermen issue the earliest known municipal regulation in the Low Countries on medicine and midwifery.[57]

- 1429 – Wein van Cotthem becomes chaplain of Dry Borren.

- 1430 – 4 August: The city becomes part of the Burgundian State when it is inherited by Duke Philip the Good following the death of Duke Philip of Saint-Pol.[58]

- 1436 – Rogier van der Weyden is appointed city artist.[4]

- 1444 – 4 March: Count Charles the Bold lays the foundation stone of the right wing of the Town Hall.[59]

- 1452 – Manneken Pis is first mentioned as Julisenken Borre.[60]

- 1455

- The Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament of the Miracle is built.

- The Town Hall is completed.[4]

- 1456 – 7 September: The Charterhouse of Scheut led by prior Hendrik van Loen is established.

- 1457 – The Dominicans are authorised to establish a presence in the city and relocate to Lange Ridderstraete.[61]

- 1461 – The legislative powers of the aldermen are reduced under the Sentence of Saint-Omer.[58]

- 1463 – The Chapel of Boondael is founded by William of Hulstbosch.

- 1464 – Population: c. 39,000.[4]

- 1467 – 24 October: The Joyous Entry of Duke Charles the Bold into the city takes place.[59]

- 1473 – Disliking the city, Charles the Bold moves the Chamber of Accounts of Brabant to Mechelen, making it the financial and judicial capital.[59]

- 1476–1476 – The city's first printing press is established by the Brethren of the Common Life.[62][63]

- 1477

- The Habsburgs come to power in the Burgundian Netherlands, with the city as their capital.[64]

- March: A popular insurrection under Willem van Marbais, Jan Bogaert and Willem van Ruysbroeck takes place.[4]

- The Harquebusiers of St. Christopher are established.[16]

- 11 February: Duchess Mary of Burgundy grants the Great Privilege, which restores the liberties of the States General abrogated by her father and grandfather.[65]

- 4 June: The Joyous Entry of Duchess Mary of Burgundy into the city takes place.

- 1479 – 13 October: De Corenbloem chamber of rhetoric is first attested.[66]

- 1480 – The Royal Oath of St. Michael and St. Gudula or the Fencers of Brussels is established.[67][16]

- 1486

- De Lelie chamber of rhetoric is first attested following the Joyous Entry of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor.[68]

- 6 May: De Violette chamber of rhetoric is first attested.[69]

- 1487 – The Kluis in Neder-Heembeek is founded by Nicolas de Vucht.[70]

- 1488

- 18 September: Philip of Cleves enters the city through the Flanders Gate at the head of a French-Flemish army.[71]

- 20 September: The city proclaims the Peace of Bruges, officially joining the Flemish Revolt.[71]

- November: The city attempts to capture Beersel Castle but fails.[72]

- 1489

- 23 January: An ordinance declares the city's support for Philip of Cleves and threatens sanctions against supporters of Maximilian I.[71]

- April: The city besieges and captures Beersel Castle; William of Ramilly and several soldiers are lynched at the Grand-Place.[73][71]

- 14 August: The Peace of Danebroek is signed, punishing the city and Leuven for their roles in the Flemish Revolt.[71]

- 1499 – 25 February: The Brotherhood of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows is established by members of De Lelie and De Violette.

16th century

- 1502–1503: Two preachers who condemn the veneration of the Virgin Mary are burned at the stake.[74]

- 1507 – 15 September: 't Mariacranske chamber of rhetoric is established following the merger of De Lelie and De Violette, with Jan Smeken becoming its first factor.[75]

- 1511 – The Miracle of 1511 takes place.

- 1513 – Adriaan Florensz Boeyens, the future Pope Adrian VI, is appointed dean of the chapter of St. Guido in Anderlecht.[76]

- 1515 – 28 January: The Joyous Entry of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and Philip the Prudent into the city takes place.

- 1516

- Johann Baptista von Taxis is appointed the first master-general of the mails by Emperor Charles V and creates a postal link between the city and Vienna.[77]

- 4 December: The Treaty of Brussels is signed, ending the War of the League of Cambrai.

- 1518 – 30 August: Lauken van Moeseke is decapitated for doubting the value of the sacraments.[74]

- 1521

- Lutheran books are prohibited.[74]

- May–October: Erasmus moves to Anderlecht for health, political, and religious reasons and stays in the house of Canon Peter Wijchmans.

- 1522

- September: The Amigo Prison is built.

- 8 February: The Treaty of Brussels between Charles V and Archduke Ferdinand, concerning the latter's sovereignty over the Austrian Hereditary Lands, is signed.

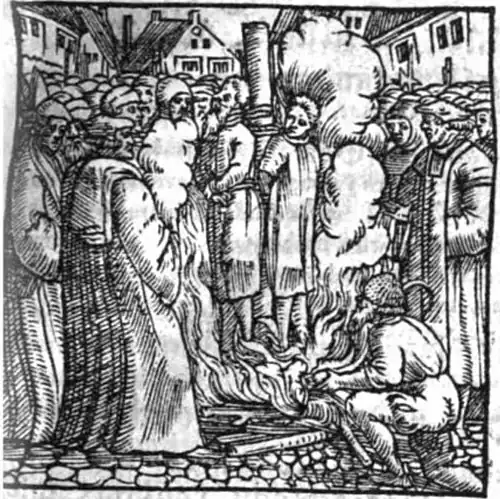

- 1523

- January: Maximilianus Transylvanus publishes De Moluccis Insulis, a key source on the Magellan expedition.

- 1 July: Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos are burned at the stake at the Grand-Place, becoming the first victims of the Inquisition in the Netherlands.

- 1526

- Pronouncing Martin Luther's name is prohibited.[74]

- 20 October: A fire destroys three houses in the Rue des Six Jetons/Zespenningenstraat.[39]

- 1527 – Several tapestry weavers, including Pieter de Pannemaker, are punished for attending sermons by the Lutheran Claes van der Elst.[74]

- 1528 – 15 September: Lambrecht Thorn, a collaborator of Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos, dies in captivity.

- 1530s – Munsterites and Mennonites arrive in the city.[74]

- 1531 – April: Governess Mary of Hungary enters the city with Charles V and makes the city the official capital of the Netherlands and permanent seat of the court.[78]

- 1536 – The original King's House is built on the Grand-Place for the Duke of Brabant.[79]

- 1539 – 3 January: The Supreme Charity is established in response to Charles V's 7 October 1531 edict, which banned begging and centralised town welfare revenue to combat pauperism.[80]

- 1543

- Brussels lace is explicitly mentioned for the first time in a list of presents given to Princess Mary for New Year's.[81]

- Calvinists establish Dutch- and French-speaking communities in the city, the latter mostly composed of court nobility and the wealthy, meeting in secret conventicles.[74]

- 1544 – Andreas Vesalius moves into a large estate in Hellestraetken, near today's Rue des Minimes/Minimenstraat.

- 1547 – Municipal liberties are codified.[82]

- 1549 – 1 April: A grand tournament is held on Haerenheydeveldt to mark the visit of Prince Philip during his tour of the Netherlands following his investiture.[83]

- 1550 – The Granvelle Palace is built.[84][85]

- 1554 – Margaretha von Waldeck, allegedly the inspiration for Snow White, died in the city, with chronicles suggesting she may have been poisoned with arsenic.[86]

- 1555 – 25 October: Charles V abdicates in the Aula Magna of the Palace of Coudenberg.[4]

- 1556 – 7 January: A decree forbids wooden dwellings, but the law is not enforced.[53]

- 1559 – 12 April: Philip the Prudent establishes the Royal Library of the Low Countries, using the Library of the Dukes of Burgundy as its core collection.[87][88]

- 1561 – 12 October: The city's port and the Willebroek Canal are opened.[89]

- 1564

- Docks are constructed on the wasteland between the two city ramparts.[12]

- 16 November: Jan Pannant is executed at the Grand-Place using a breaking wheel for double homicide and theft, as later described in the diary of Jan de Pottre.

- 1565 – 11 November: The wedding of Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma, and Maria of Portugal, Hereditary Princess of Parma, takes place.[90]

- 1566

- 5 April: The signatories of the Petition of the Nobles gain access to the Palace of Coudenberg to present it to Margaret of Parma.

- 6 April: The banquet of the Geuzen is held by the Compromise of Nobles in the Court of Culemborg.

- June: Large preachings occur as iconoclasts wreak havoc, and Protestants throw the 15th-century Black Madonna statue into the Senne.[74]

- 1567

- 22 August: Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, arrives in the city.[4]

- 30 August: Margaret of Parma resigns as Governess of the Netherlands and flees the city.

- 9 September: The Council of Troubles is established.

- 1568

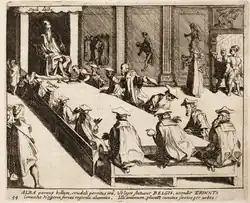

- 1 June: Eighteen signatories members the Compromise of Nobles are decapitated at the Peerdemerct.[4]

- 5 June: The Counts of Egmont and Horn are executed at the Grand-Place.

- 1569 – A knighting and jousting tournament held in honour of the Duke of Alva at the Grand-Place.[12]

- 1570 – 11 February: Jan Grauwels, the Provost of Justice, is hanged for abusing his power in the conviction of the Geuzen.[12]

- 1573 – Many Protestants return to the city after being executed and expelled.[74]

- 1574 – A pilgrim returning from Palestine notices a resemblance between the Valley of Josaphat and the Valley of the Roodebeek, renaming it and later erecting a column on the Heiligenberg.[22]

- 1575

- 1576 – 4 September: The Calvinist Republic of Brussels is founded following the imprisonment of the Council of State and the Secret Council.

- 1577

- 9 January: The First Union of Brussels is established by the States General of the Netherlands.[91]

- 24 July: The Coup of Namur occurs, ending the First Union of Brussels.

- 10 December: The Second Union of Brussels is declared.[92]

- 24 September: The Joyous Entry of William the Silent into the city takes place.

- 1579

- The city joins the Union of Utrecht.[93]

- 6 June: The Great Beguinage is looted by Scottish auxiliary troops as part of the larger Beeldenstorm.[94]

- 1580

- 1581 – Spanish troops under Alexander Farnese burn Ixelles to the ground.[96]

- 1585 – 10 March: The city is besieged by the Army of Flanders.[97][98]

- 1587 – 20 July: During a mystery play performed by the Brethren of the Common Life, a lodge collapses, killing the author Petrus Fabri and alderman Eustachius Pipenpoy, and injuring several spectators.[63]

- 1589 – October: The city grants the Augustinians a tax exemption in exchange for holding mass at the Town Hall for three months each year and serving as firemen when needed.[99]

- 1590 – 31 March: The city decides to construct the Simpelhuys, a complex featuring residential blocks, kitchens, a bakery, and cells for the mentally ill.[100]

- 1594

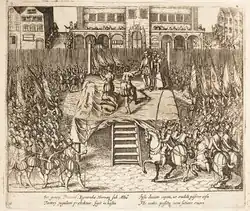

- 30 January: The Joyous Entry of Archduke Ernest of Austria into the city takes place.[101]

- 21 December: Anna Utenhoven, arrested with Anna and Catharina Rampaerts, is found guilty of heresy and buried alive on the Haerenheydeveldt, becoming the last heretic executed in the Low Countries.

- 1595

- The Niederländische Postkurs postal service is established in the city.

- 13 September: Josyne van Beethoven is burned at the stake at the Grand-Place for witchcraft.[102]

- 1598 – The Royal Guild of St. Sebastian of Schaerbeek is founded as a branch of the Royal Grand Oath of the Archers of St. Sebastian.[49]

- 1599

- 13 July: An ordinance mandates that slackers are both to be branded and flogged.[103]

- 5 September: The Joyous Entry of Albert VII, Archduke of Austria, and Isabella Clara Eugenia into the city takes place.[4]

- 14 November: Joanne Berkeley is installed as the first abbess of the Abbey of Our Lady of the Assumption by Archbishop Mathias Hovius.[104]

17th century

- 1604 – 16 July: St. John Berchmans College is established.

- 1607 – The Discalced Carmelite Convent is established by Ana de Jesús.

- 1612 – Upon his death, Priest Nicaise Mozet establishes the Fondatie op het Kerkhof a small hermitage for women.[22][105]

- 1616 – 1 September: The Annonciades Convent is established.

- 1618 – 28 September: The Mount of Piety opens.

- 1619

- Jérôme Duquesnoy is commissioned to recast Manneken Pis in bronze for 50 florins.[60]

- 12 July: A riot breaks out after the city imposes a tax on wine and beer (the gigot).[4]

- 16 December: Daniel Raessens is tasked with providing the pedestal for Manneken Pis for 180 florins.[60]

- c. 1620 – The Mesthoop is created near the Rue d'Ophem/Oppemstraat as a collection point for human and animal waste for rural disposal, while industrial waste is dumped into the Senne.[38]

- 1622 – The funeral of Archduke Albert VII takes place.

- 1623

- The Bridgettines Convent is established.

- The Brotherhood of St. Hubertus is established.[106]

- 1624 – The Brotherhood of St. Joseph is established.[107]

- 1625

- 1631 – The Brotherhoods of St. Eligius and St. Guido are established for the coachmen of the Court under the protection of the Infanta Isabella.[108][109][110]

- 1634 – In a sparsely populated area at the end of the Rue de Laeken/Lakensestraat, a house is constructed to isolate and care for plague sufferers.[12]

- 1638 – 12 May: The Royal Brotherhood of the Holy Name of Mary is established.[111]

- 1646

- The Small Beguinage of Brussels is founded.

- 6 October: Purple rain falls on the city; the downpour elicits scientific examination and explanation.[4]

- 1648 – The Confraternity of St. Dorothea is established.

- 1654 – The Barony of Jette is formed.[112]

- 1656 – During the Counter-Reformation, Protestants hold secret services until chapels open in the Dutch embassy and the English mission, allowing public worship.[74]

- 1657 – De Wijngaard theatre company is established, possibly out of 't Mariacranske.[113]

- 1659 – The Barony of Jette is elevated to a county.[112]

- 1668

- 7 June: The city enacts an ordinance to combat the Black Death and appoints a Plague Master to oversee the care of the sick.[114]

- 27 July: To prevent the spread of the Black Death, the city restricts movement to evenings, bans gatherings, and prohibits the sale of certain foods, while confiscating and destroying grain, flour, and meat.[114]

- 1669 – 13 October: The St. Landry Chapel is consecrated.[115]

- 1670 – 7 January: A posthumous mass is held in honour of the victims of the Black Death.[114]

- 1672 – The Fort of Monterey is built.

- 1675 – The Royal Military and Mathematics Academy of Brussels is established.[116]

- 1677 – Evere is incorporated into the Principality of Hornes after its lord, Eugene Maximilian of Hornes, is elevated to the rank of prince by King Charles II of Spain.

- 1682 – 24 January: The Opéra du Quai au Foin opens as the first public theatre in the city.

- 1684

- French invaders ravage Koekelberg, Molenbeek, and Linkebeek.[82]

- 17 January – 400 French cavalrymen set fire to several dozen small houses in Ixelles.[96]

- 1686 – 3 September: The Palace of Thurn and Taxis on the Sablon hosts a grand banquet to celebrate the Holy League's victory in the Siege of Buda. Fireworks light up the Sablon, attracting a crowd.[12]

- 1690 – 11–12 October: A fire breaks out in La Louve/De Wolvin guildhall on the Grand-Place.

- 1691 – The Apostolines settle in Bavendal.

- 1695

- 13–15 August: The city is bombarded by the French, destroying a third of its buildings, including the Grand-Place.

- 19 August: Manneken Pis is returned, with Latin verses, after citizens removed the statue to protect it during the bombardment.[60]

- 1696 – 7 November: The Tour du Miroir collapses.[117]

- 1697–1698: Reconstruction of the Grand-Place is largely completed.[4]

- 1698 – 1 May: Manneken Pis receives his first costume from Governor Maximilian II Emanuel of Bavaria.[60][118][119]

- 1699 – 17 December: The Den Luyster en de glorie van het hertogdom van Brabant, a compendium of rights and privileges granted to the Nine Nations, is banned, sparking armed resistance met by Spanish and Bavarian battalions.[82][117]

- 1700

- April: The Luyster van Brabant conflict ends.

- 20 August: Governor Maximilian II Emmanuel issues the Additional Decree, tightening royal control and curbing local powers.[82]

- 17 October: The first Theatre of La Monnaie, then spelled La Monnoye, opens.

18th century

- 1701 – The Nassau Palace suffers extensive damage from a fire.

- 1702

- 1703 – 3 February: The Chamber of Commerce and Industry is founded by Isidro de la Cueva y Benavides, much to the displeasure of the Drapery Court.[122]

- 1705 – The Fort Jaco is built.

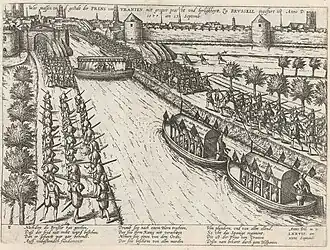

- 1706 – 27 May: The English–Dutch army enters the city trough the Laeken Gate after the French defeat at the Battle of Ramillies.[4][123]

- 1708 – 22–27 November: The city is attacked by the French, which it repels.

- 1711 – 30 September: The Royal Academy of Fine Arts is established.[4]

- 1714

- March 6: The Treaty of Rastatt is signed; the city becomes part of the Austrian Netherlands.[4]

- 25 July: The Belfry of Brussels collapses.

- 1717

- 14–18 April: Peter the Great visits the city.[4][124]

- 5 November: The Theatre of La Monnaie is publicly sold to Jean-Baptiste Meeûs.[121]

- 1719 – 19 September: François Anneessens is executed at the Grand-Place.

- 1724 – March: The Senne floods: The lower city is 3 feet underwater.[125]

- 1731 – 3–4 February: The Palace of Coudenberg is destroyed by fire, killing 1.[4][126]

- 1733 – 10 February: The city instructs gravediggers to bury corpses at least three feet deep to prevent dogs from uncovering them and causing infections.[46]

- 1744 – Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine enters the city.

- 1745 – Manneken Pis is stolen by the English and taken to Geraardsbergen, later returned by its residents.[60]

- 1746 – 29 January–22 February: The city is besieged and captured by the French.

- 1747 – King Louis XV gifts Manneken Pis his oldest surviving outfit and makes him a knight of the Royal and Military Order of Saint-Louis after his soldiers stole the statue.[127]

- 1749 – January: The city is returned to Austria with the rest of the Austrian Netherlands following the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.

- 1751 – The Fountain of Minerva, gifted by Thomas Bruce, 2nd Earl of Ailesbury, is built.

- 1755 – Population: 57,370.[4]

- 1762 – Despite official disapproval, 400 Protestant exiles arrive from Geneva.[74]

- 1767 – The first census of the inhabitants of the city occurs.[12]

- 1769 – Vanparys Confiserie is established by Felix Vanparys.

- 1770 – The original pedestal of Manneken Pis is replaced with a stone niche intended for the Place de la Chapelle/Kapellemarkt fountain.[60]

- 1771–1778 – Au Vieux Spijtigen Duivel is first attested on the Ferraris map.

- 1772

- The Opéra flamand is established.

- Faro is first attested.

- 16 December: The Imperial and Royal Academy is established.[128]

- 1774 – The Rue Royale/Koningsstraat is laid out.[29]

- 1775

- Brussels Park is laid out.

- The Place des Martyrs/Martelaarsplein, then called the Place Saint-Michel/Sint-Michielsplein, is laid out.[4]

- 1777 – 1 October: The Theresian College opens.[129][130]

- 1778 – The Palace of the Council of Brabant (present-day Palace of the Nation) begins construction.

- 1779

- The Brussels Arsenal is built.

- Governor Charles Alexander hosts the first horse races outside the British Empire at the Monplaisir Château.[22]

- 1781 – Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor visits the city.

- 1782

- The Place Royale/Koningsplein is laid out.

- Emperor Joseph II orders the dismantling of the city's fortifications; the Fort of Monterey is sold and destroyed.

- 1 May: The brothers Alexandre and Herman Bultos receive permission to construct the Royal Park Theatre as an annex to the Theatre of La Monnaie.[131]

- 1783

- English residents establish an Anglican church.[74]

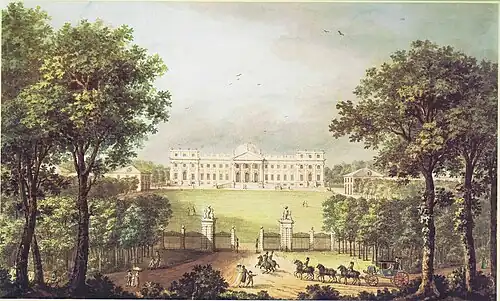

- The Royal Palace of Brussels begins construction.

- 1784

- The city's gates are demolished, except for the Halle Gate and the Laeken Gate.

- The Palace of Schonenberg (present-day Palace of Laeken) is built.

- 1785 – The Concert Noble is founded by the Governors Albert Casimir and Maria Christina.[132]

- 1787

- The Vauxhall opens.

- 4 June: The deans of the Nine Nations call for a citizens' guard, and artisans, merchants, and residents wearing patriotic cockades rally in response.

- 20 September: A fight erupts outside a café between guards and Austrian troops, killing one guard.[133]

- 21 September: At the guard's funeral, Austrian troops advance on the Church of St. Gaugericus, sparking street fighting as residents rush to the Grand-Place, build barricades, and force the Austrians to withdraw and annul unpopular decrees.[133]

- 29 October: The Church of St. James on Coudenberg is consecrated.

- 1788 – 22 January: A day after his arrival, troops under General Richard d'Alton open fire on an unarmed demonstration at the Grand-Place, killing several.[133]

- 1789

- Emperor Joseph II abolishes all provincial privileges, including the Joyous Entry, and announces he will rule alone, bypassing the States of Brabant.[133]

- The secret society Pro Aris et Focis is founded to prepare for the Brabant Revolution against Emperor Joseph II.[134][135]

- 8–9 December: Villagers around the city attack Austrian garrisons.[133]

- 10–12 December: The Battle of Brussels takes place, marking the start of the Brabant Revolution in the city.

- 18 December: A celebratory procession is held to mark the Austrians' retreat.[133]

- 1790

- 10 January: The States General proclaim the United Belgian States;[133] Governors Albert Casimir and Maria Christina flee the city to Vienna.[136]

- 11 January: The city becomes the capital of the United Belgian States.

- 6 October: Willem van Criekinge is lynched after insulting the Capuchin Josse Huyghe during a Marian procession.

- 2 December: The Austrians take the city back and pledge to reverse the reforms of Joseph II.

- 1792

- 13 November: The Battle of Anderlecht occurs between Habsburg Empire and the French First Republic.

- 14 November: Following the French victory the previous day, General Charles-François Dumouriez enters the city to cheering crowds, as several Walloon soldiers join the French Army.[4][137]

- 15 December: A decree by the French National Convention dissolves local authorities, abolishes traditional taxes, and orders municipal governments to provide troops for France.[137]

- 29 December: Elections result in a majority for traditionalists, while democratic activists win seats in a provisional provincial assembly due to a single permitted polling station, the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula.[137]

- 1793

- January: Street names are changed, symbols of royal authority removed, and religion is demeaned.[137]

- 27 February: Residents vote for union with France in French-supervised elections, while church statues are destroyed, archives burned, and homes looted.[137]

- 24 March: Promising to restore traditional institutions, the Austrians return to a warm welcome as supporters of the old provincial States, the nations, and the high clergy rally citizens against the French.[137]

- 9 August: An explosion of gunpowder-laden carts causes widespread destruction in Cureghem/Kuregem.[138]

- 1794: 9 July: French troops re-enter the city after the Austrian defeat at the Battle of Fleurus.[137]

- 1795 – 1 October: The city is formally annexed by France and becomes the chef-lieu of the department of the Dyle.[137]

- 1796

- The Guilds of Brussels are suppressed.[139]

- La Cambre Abbey and Forest Abbey are abolished.

- The Church of St. Gaugericus is demolished.

- 17 June: The civil registry is introduced.[12]

- 1797

- 31 May: The École centrale du département de la Dyle is established, replacing the Old University of Leuven.

- 4 September: The Coop of Brussels is abolished, prompting protests from municipal authorities.[4]

- 17 December: Brussels Park is officially opened as a public park.[12]

- 1798

- 27 May: The city renames streets with religious or monarchist connotations to more republican names, as required by the French administration.[12]

- 7 December: Prisoners of war from Hasselt, captured for participating in the Peasants' War, are paraded through the streets.[140]

- 1800

- Population: 66,297.[4]

- 10 January: The Société de littérature de Bruxelles literary society is established.

- 15 August: The Fire Brigade is established, marking the formation of Belgium's first professional firefighting unit.

19th century

20th century

21st century

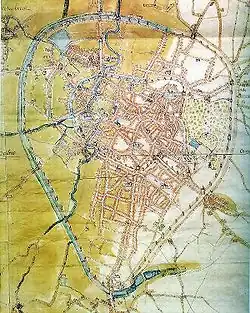

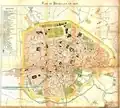

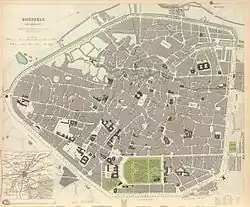

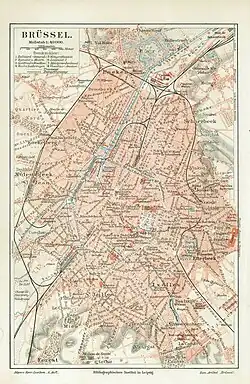

Evolution of the Brussels map

16th century

-

1555

1555 -

1567

1567

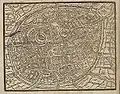

17th century

-

1610

1610 -

~1657

~1657

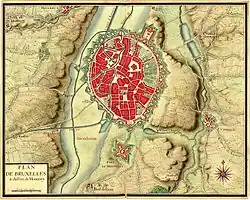

18th century

-

~1700

~1700 -

~1711

~1711 -

1740

-

~1745

~1745 -

1777

1777

19th century

-

1830

1830 -

1837

1837 -

1843

1843 -

1876

1876 -

.jpg) 1894

1894

20th century

-

%252C_Bruxelles_et_sa_banlieue%252C_1900.png) 1900

1900 -

1907

1907

See also

- History of Brussels

- List of mayors of the City of Brussels (largest municipality in the Brussels-Capital Region)

- List of municipalities of the Brussels-Capital Region

- Timeline of Belgian history

- Timelines of other municipalities in Belgium: Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Leuven, Liège

References

- ^ a b c d e "INLEIDING TOT DE GESCHIEDENIS VAN UKIŒL" (PDF). Ucclensia (14): 22. 14 March 1968.

- ^ a b c d Charruadas, Paulo. "De eerste volkeren in de Brusselse regio". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - resume_poster_Prignon.doc". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw State, Paul F. (2004). Woronoff, Jon (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Brussels (PDF). United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc. ISBN 0-8108-5075-3.

- ^ "Archeologische site in Laarbeekbos krijgt infoborden". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ "De Frankische tijd". www.delbeccha.be. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ State, Paul F. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Brussels. Scarecrow Press. p. 269.

- ^ Bart Fransen, "Recherches historiques / Historisch onderzoek", Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, 32 (2006–2008), p. 95–101

- ^ "CatholicSaints.Info » Blog Archive » Weninger's Lives of the Saints – Saint Guido, Confessor". Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ De Sancto Verono Lembecae et Montibus Hannoniae.

- ^ a b Charruadas, Paulo. "De geboorte van Brussel. De vroegste ontwikkeling". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Brusselse chronologie". www.tiki-toki.com. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse lepralijders". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Hennaut, Eric; Hulsbosh, Laurent. De Grote Markt van Brussel. Solibel Edition.

- ^ "Ancien Grand Serment Royal et Noble des Arbalétriers de Notre Dame du Sablon". Erfgoedcel Brussel (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Vaandels van de Wapengilden van Brussel (Ommegang van Brussel): Grand Serment Royal et Noble des Arbalétriers de Notre-Dame du Sablon / Koninklijke Vereniging". collections.heritage.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ Charles Harrison Townsend (1916), Beautiful buildings in France & Belgium, New York: Hubbell, OL 7213871M

- ^ "Café du Heideken". www.reflexcity.net. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ a b c "Taxes and Tolls". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ "De keure van 1229", Brussel: Waar is de Tijd, 6 (1999), pp. 133-135.

- ^ "Begijnhof – Inventaris van het bouwkundig erfgoed". monument.heritage.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Schaarbeek door de jaren heen | Schaarbeek". Schaerbeek 1030 Schaarbeek (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Online, Catholic. "St. Boniface of Lausanne - Saints & Angels". Catholic Online. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ De Bardzki-Granon, Anne. "De Bezemhoek: Een wijk tussen water en woud". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ "Beghards". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ "Cloth". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Risings of 1303 and 1306". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ "1080 Molenbeek-Saint-Jean". Health centre le foyer. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ a b Grant Allen (1904), Belgium: its cities, Boston: Page, OL 24136954M

- ^ Bassens, Maarten (February 2013). "De Wildewoudstraat" (PDF). In de Kijker.

- ^ "Charte Jean II de Brabant 1306 | Lignages de Bruxelles" (in French). Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Histoire". www.meyboom.be. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Etterbeek/Etterbeek". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ "Grote Zavel – Inventaris van het bouwkundig erfgoed". monument.heritage.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "Hoeve van Elishout – Inventaris van het Natuurlijk Erfgoed". sites.heritage.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Vannieuwenhuyze, Bram (2008). Brussel, de ontwikkeling van een middeleeuwse stedelijke ruimte (PDF) (in Dutch).

- ^ NWS, VRT (22 January 2020). "Waarom een monnik het hoofd van "de eerste feministe" van Brussel verplettert in de kathedraal". vrtnws.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Sanitation". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ a b c Vannieuwenhuyze, Bram. "Brussel in vuur en vlam. Feiten, preventie, bestrijding en verwerking van historische stadsbranden" (PDF). Tijd-Sc (2): 20.

- ^ Rebecca (30 June 2021). "The Nassau Chapel: the story of the court chapel that became a museum (part 1) • KBR". KBR. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "L'Ommegang". patrimoine.brussels (in French). Direction du Patrimoine culturel.

- ^ Cluse, C.M. "De jodenvervolgingen ten tijde van de pest (1349-50) in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden" (PDF).

- ^ "Rising of 1360". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ "Belgique : Le pays de la bière". www.beerwulf.com (in French). Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Over ons - Belgian Brewers". belgianbrewers.be (in Dutch). 30 April 2024. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Verloren verleden: Het begraven van de doden". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Lignages". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ "Un peu d'histoire". GSR BXL (in French). Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Archive : La guilde de Saint Sebastien". Schaerbeek 1030 Schaarbeek (in French). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Histoire". www.gsrb.be. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ "Immigrants". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ a b Sleiderink, Remco; Vannieuwenhuyze, Bram (2012). "Everard t'Serclaes: Beeldvorming en lieux de mémoire rond een Brusselse stadsheld" (PDF). Tijd-Schrift.

- ^ a b c "Firemen". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ "Anthony of Burgundy". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e "Rising of 1421". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ David M. Nicholas, The Later Medieval City: 1300–1500 (Routledge, 2014), p. 139.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse vroedvrouwen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Philip the Good". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ a b c "Charles the Bold". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wikeo.net, Manneken Pis via. "Histoire de la Statuette". Ordre des Amis de Manneken-Pis (in French). Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse dominicanen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ Robert Proctor (1898). "Books Printed From Types: Belgium: Bruxelles". Index to the Early Printed Books in the British Museum. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company. hdl:2027/uc1.c3450632 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ a b "Verloren verleden: Broeders van het Gemene Leven". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ BBC News (29 February 2012). "Belgium Profile: Timeline". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Mary of Burgundy". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ DBNL. "De Corenbloem, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ "De Wapengilden van Brussel — Patrimoine - Erfgoed". erfgoed.brussels. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "De Lelie, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "De Violette, Repertorium van rederijkerskamers in de Zuidelijke Nederlanden en Luik 1400-1650, Anne-Laure Van Bruaene". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Billen, Claire; de Waha, Michel. "De luister van een hoofdstad. Een hoofdstad van Zuid-Brabant". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ a b c d e Vrancken, Valerie (2015). "Opstand en dialoog in laatmiddeleeuws Brabant. Vier documenten uit de Brusselse opstand tegen Maximiliaan van Oostenrijk (1488-1489)". Bulletin de la Commission royale d'Histoire. 181 (1): 209–266. doi:10.3406/bcrh.2015.4321.

- ^ "Beersel Castle". www.werbeka.com. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ "Het kasteel van Beersel". Historiek (in Dutch). 11 October 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Protestants". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ DBNL. "DBNL rederijkerskamer - Het Mariacransken". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 July 2024.

- ^ Weel, Gerard. Paus Hadrianus VI volgens Caspar Burman (PDF).

- ^ "Tour & Taxis". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ "Mary of Hungary". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ Hennaut 2000, p. 17.

- ^ N., R. (1932). "Bonenfant (Paul). — La création à Bruxelles de la Suprême Charité. Annexe au Rapport annuel de la Commission d'Assistance publique de la ville de Bruxelles pour 1928, 1930". Revue du Nord. 18 (71): 231.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes (1903). Lives of the queens of England, from the Norman conquest;. unknown library. Philadelphia, Printed for subscribers by G. Barrie & son.

- ^ a b c d "Spanish Regime". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ Demeter, Stéphane; Paredes, Cecilia. "Een uitzonderlijk toernooi in Evere op 1 april 1549". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ Martens, Pieter (2019). "Planning Bastions: Olgiati and Van Noyen in the Low Countries in 1553" (PDF). Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 78. Brussels: Vrije Universiteit Brussel: 25–48. doi:10.1525/jsah.2019.78.1.25.

- ^ De Jonge, Krista; Janssens, Gustaaf (2000). Les Granvelle et les anciens Pays-Bas. Symbolae Facultatis Litterarum Lovaniensis - Series B (in French). Vol. 17. Leuven: Leuven University Press. ISBN 978-90-5867-049-6.

- ^ NWS, VRT (5 February 2024). "Ligt Sneeuwwitje begraven onder de Beurs in Brussel?". vrtnws.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ "Belgium has been hiding a treasure for 600 years • KBR". KBR. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Manuscripts and Rare books • KBR". KBR. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ "Tijdsbalk - 1560 tot 1570 jaar in onze jaartelling" (in Dutch). willebroek.be. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- ^ Jamieson, Frances (formerly Thurtle) (1820). The History of Spain, from the Earliest Ages ... to the Return of Ferdinand VII. in 1814. Whittaker.

- ^ DBNL. "24 First Union of Brussels, 9 January 1577, Texts concerning the Revolt of the Netherlands, E.H. Kossmann, A.F. Mellink". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ DBNL. "29 Second Union of Brussels, 10 December 1577, Texts concerning the Revolt of the Netherlands, E.H. Kossmann, A.F. Mellink". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Unie van Utrecht". NEMOKennislink (in Dutch). Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Vanden Bossche, Hugo. "Deel 4: Begijnhofkerk Sint-Jan-de-Doper" (PDF). Begijnhofkrant (49).

- ^ van Stipriaan, René (2021). De zwijger. Het leven van Willem van Oranje. p. 610.

- ^ a b "Ixelles/Elsene". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ "Farnese, Alessandro", in Historical Dictionary of Brussels, by Paul F. State (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015 p.163

- ^ Demetrius C. Boulger, The History of Belgium: Cæsar to Waterloo (Princeton University Press, 1902) p.335

- ^ "Verloren verleden: De Brusselse augustijnen". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Verloren verleden: Waanzin in het Simpelhuys". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Anonymous, German, 16th century | Entrance of the Archduke Ernest to Brussels, January 30, 1594". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1594. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ De Schrijver, Machteld. Een voorouder van Ludwig Van Beethoven als heks verbrand (PDF) (in Dutch).

- ^ a b "Verloren verleden: Dwangarbeid in het Deuchthuys". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Berkeley, Joanne [name in religion Joanna] (1555/6–1616), abbess of the Convent of the Assumption of Our Blessed Lady, Brussels". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/105817. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1. Retrieved 4 October 2024. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Schaerbeek, Archives de (16 June 2019). "Quelques noms de rues disparus à Schaerbeek | Een paar verdwenen stratennamen in Schaarbeek". ArchivIris (in French). Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Brotherhood of Saint Hubertus". Eglise du Sablon. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Register of the Brotherhood of Saint Joseph". Eglise du Sablon. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Groot Broederschap van de Heilige Sint-Guido stelt zichzelf tentoon". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "De Swaene | broederschap-van-sint-guido-2023". De Swaene (in Flemish). Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ "Book of the Brotherhood of Saint Eligius and Saint Guido". Eglise du Sablon. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ "Royal Brotherhood of the Holy Name of Mary". Eglise du Sablon. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b "Commune de Ganshoren". ArchivIris (in French). 17 June 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Sleiderink, Remco; Geysen, Frederik. "Uitzonderlijke onthulling van het oudste archiefstuk in het AMVB" (PDF). Arduin (15).

- ^ a b c "Verloren verleden: De pest in Brussel". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "Domein Drie Fonteinen". inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be (in Dutch). 8 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ Kashima, Akihiro. City Planning and Architectural Education in the Establishment of the Academies in 18th-Century Spain (PDF). The Second Asian Conference of Design History and Theory – Design Education beyond Boundaries – ACDHT 2017. Tsuda University, Tokyo. p. 46.

- ^ a b "Luyster van Brabant". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 5 April 2025.

- ^ De Roose, Fabien (1999). De Fonteinen van Brussel [The Fountains of Brussels] (in Dutch). Brussels. ISBN 978-90-209-3838-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Henne & Wauters 1845.

- ^ "Book of the Brotherhood of Saint Aubert". Eglise du Sablon. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ a b Vachaudez, Christophe. "La Dolce vita: het mondaine leven in de Oostenrijkse Nederlanden". Erfgoed Brussel.

- ^ "Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie de Bruxelles". search.arch.be. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ "Anjouin Period". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 2 April 2025.

- ^ DBNL. "Tsaar Peter de Grote: identiteit en imago Rietje van Vliet, Literatuur. Jaargang 13". DBNL (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 July 2024.

- ^ "KMI - 16de - 18de eeuw - Ancien Régime". KMI (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "De verdwenen geschiedenis van het Coudenbergpaleis: 'Een zoo onder het Koningsplein'". www.bruzz.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 12 March 2025.

- ^ "The oldest outfit in the collection". GardeRobe MannekenPis. Retrieved 6 October 2024.

- ^ James E. McClellan (1985). "Official Scientific Societies: 1600-1793". Science Reorganized: Scientific Societies in the Eighteenth Century. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-05996-1.

- ^ Vanwelkenhuyzen, Michel (9 December 2022). "Le Collège Thérésien". Studia Bruxellae (in French). 13 (1): 11–26. doi:10.3917/stud.013.0011. ISSN 2030-5974.

- ^ Kreins, Jean-Marie. "Renouveler ou renouer ? La Commission royale des Etudes et le Collège - Pensionnat de Luxembourg (1773-1777-1789)".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "L'histoire du Parc". Théâtre Royal du Parc. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ "heritage days / open monumentendagen - Concert Noble". heritagedays.urban.brussels (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Brabant Revolution". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ "Jean-François Vonck | Belgian Revolution, Constitutional Reforms, Political Reformer | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 October 2024.

- ^ Polasky, Janet. Revolution in Brussels 1789-1793 (PDF). Académie Royale de Belgique.

- ^ "Politieke spanningen tijdens Brabantse Omwenteling". Historiek (in Dutch). 4 December 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "French Regime". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Levarlet, Henri (1941). "Accidents survenus en Belgique dans la fabrication, l'emmagasinage et le transport des explosifs" (PDF). biblio.naturalsciences.be (in French). pp. 467–468. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ A. Graffart, "Register van het schilders-, goudslagers- en glazenmakersambacht van Brussel, 1707–1794", tr. M. Erkens, in Doorheen de nationale geschiedenis (State Archives in Belgium, Brussels, 1980), pp. 270–271.

- ^ "Boerenkrijg (1798) | Belgium Battlefield of Europe". belgiumbattlefield.be. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

Bibliography

In English

- Published in the 19th century

- New Picture of Brussels, and its Environs, or, Stranger's Guide to the Curiosities of that Interesting City, London: Samuel Leigh, 1820, OCLC 63579821

- "Brussels". Galignani's Traveller's Guide through Holland and Belgium (4th ed.). Paris: A. and W. Galignani. 1822. hdl:2027/njp.32101073846667.

- David Brewster, ed. (1830). "Brussels". Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

- "Brussels", Cabinet Cyclopædia, vol. Cities and Principal Towns of the World, London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, & Green, 1830, OCLC 2665202

- "Brussels", A hand-book for travellers on the continent (2nd ed.), London: John Murray, 1838, OCLC 2030550

- Frederick Knight Hunt (1845), "Brussels", The Rhine: its scenery & historical & legendary associations, London: Jeremiah How

- "Brussels". Coghlan's Illustrated Guide to the Rhine (18th ed.). London: Trubner & Co. 1863.

- Stranger's Guide to Brussels and its environs (6th ed.), Kiessling & Co., 1876

- W. Pembroke Fetridge (1885), "Brussels to Antwerp", Harper's hand-book for travellers in Europe and the east, New York: Harper & Brothers

- Published in the 20th century

- "Brussels". Chambers's Encyclopaedia. London. 1901. hdl:2027/njp.32101065312876 – via Hathi Trust.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ernest Gilliat-Smith (1906), The story of Brussels, London: Dent, OL 24358871M

- Ernest Gilliat-Smith (1908). "Brussels". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Brussels", Belgium and Holland, Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1910, OCLC 397759

- "Brussels". Belgium. Grieben's Guide Books. Vol. 141. London: Williams & Norgate. 1910. hdl:2027/uiuc.3096224_001.

- Published in the 21st century

- Anton Kreukels; et al., eds. (2005). "Brussels". Metropolitan Governance and Spatial Planning: Comparative Case Studies of European City-Regions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-49606-8.

- Xhardez, Catherine (2016). "The integration of new immigrants in Brussels: an institutional and political puzzle". Brussels Studies. Translated by Jane Corrigan. doi:10.4000/brussels.1434. - translation of "L’intégration des nouveaux arrivants à Bruxelles : un puzzle institutionnel et politique"

In other languages

- Almanach royal de la cour, des provinces méridionales et de la ville de Bruxelles (in French). Bruxelles: A. Stapleaux. 1817.

- Marie-Nicolas Bouillet [in French]; L.G. Gourraigne (1914). "Bruxelles". Dictionnaire universel d'histoire et de geographie (in French) (34th ed.). Paris: Hachette.

- Hennaut, Eric (2000). La Grand-Place de Bruxelles. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Henne, Alexandre; Wauters, Alphonse (1845). Histoire de la ville de Bruxelles (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Perichon.

- Spapens, Christian (2005). Les Boulevards extérieurs de la Porte de Hal à la Place Rogier. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 40. Brussels: Centre d'information, de Documentation et d'Etude du Patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-96005-026-4.

- Zeiller, Martin (1654). "Brussel". Topographia Circuli Burgundici. Topographia Germaniae (in German). Frankfurt. p. 44+.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Brussels.

- Europeana. Items related to Brussels, various dates.