Weetman Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray

The Viscount Cowdray | |

|---|---|

Pearson in 1897 | |

| President of the Air Board | |

| In office 3 January 1917 – 26 November 1917 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Rothermere |

| Member of Parliament for Colchester | |

| In office February 1895 – January 1910 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Herbert Naylor-Leyland, Bt |

| Succeeded by | Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, Bt |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Weetman Dickinson Pearson 15 July 1856 Shelley, Kirkburton, West Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 1 May 1927 (aged 70)[1] Dunecht House, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Annie Cass |

| Children | Harold Pearson, 2nd Viscount Cowdray Bernard Clive Pearson Francis Geoffrey Pearson Gertrude Denman, Baroness Denman |

| Occupation | Building contractor; politician |

| Known for | Engineering projects; oil companies; MP for Colchester; philanthropy |

Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray, GCVO, PC (15 July 1856 – 1 May 1927), known as Sir Weetman Pearson, Bt from 1894 to 1910 and as Lord Cowdray from 1910 to 1917, was an English industrialist, benefactor and Liberal politician. He built S. Pearson & Son from a Yorkshire contractor into an international builder and created the Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company, a leading early 20th century oil producer.[3] After selling Mexican Eagle in 1919, he reorganised his interests around Whitehall Securities, purchased a stake in Lazard Brothers, and expanded into newspapers. This latter move set the course for the later Pearson group’s focus on publishing.[4][5]

Background

Pearson was born on 15 July 1856 at Shelley, Kirkburton, West Yorkshire, the son of George Pearson (died 1899), owner of the manufacturing and contracting firm S. Pearson & Son, by his wife Sarah Dickinson, daughter of Weetman Dickinson, of High Hoyland, South Yorkshire.[6]

Construction

The family construction business S. Pearson & Son was founded in 1844 by his grandfather Samuel Pearson (1814–1884). Pearson took control in 1880 and moved the headquarters to London in 1884, expanding it from a Yorkshire contractor into a global civil-engineering firm.[7] Through the 1880s the firm built capability and cash flow on municipal and dock works in Britain and Canada, including the Sheffield main sewer, Halifax dock works and Empress Dock at Southampton. By the early 1890s it ranked among the largest contractors in the world.[8]

Blackwall Tunnel

In London, the London County Council accepted S. Pearson & Son’s tender of £871,000 for the Blackwall Tunnel in late 1891; work began in 1892 and the Prince of Wales opened the tunnel on 22 May 1897.[9][10]

Under LCC Engineer Alexander Binnie, the design used a Greathead-type tunnelling shield in compressed air with cast iron segment linings; at more than 6,000 ft (1,800 m) in length and 27 ft (8.2 m) external diameter it was then the largest subaqueous road tunnel attempted in Britain. The contractors’ engineer Ernest William Moir designed the shield and oversaw its use on site.[10]

The project drew a wide supply chain and workforce: the iron lining was manufactured in Glasgow, granite for the portals came from Aberdeen, Italian labourers laid the asphalt roadway, and many of the foremen were recruited from Yorkshire, reflecting Pearson’s roots. On opening, Blackwall provided the only free Thames crossing between Tower Bridge and the Woolwich Ferry (a distance of nearly nine miles), easing road access to the East End docks and industry and setting a pattern later followed on LCC subaqueous works such as the Rotherhithe Tunnel and the Greenwich foot tunnel.[10][9] It was also the first vehicular tunnel built under the Thames.[11]

Dover Harbour

In 1898 S. Pearson & Son secured the Admiralty Harbour works at Dover, a scheme designed by Coode, Son & Matthews to create a deep-water refuge for the Royal Navy. The plan comprised a further 2,000 ft (610 m) extension of the Admiralty Pier, a new Eastern Arm of about 2,900 ft (880 m), and a detached Southern Breakwater of about 4,200 ft (1,300 m), enclosing roughly 610 acres (250 ha) for the Admiralty and a separate commercial harbour of about 68 acres (28 ha).[12][13]

Construction used large mass-concrete blocks faced with granite, set from staging using heavy cranes, with foundations placed and keyed under water. Historic England notes the Eastern Arm’s blocks weighed between 26 and 42 tons and were built to the Coode, Son & Matthews design; contemporary accounts describe the use of Goliath and Titan cranes to lower the units into position.[14] [15] Sections of the enclosing walls rose some 90 ft (27 m) from seabed to parapet.[16][17]

The main works were carried out between 1898 and 1909, producing the harbour geometry that still defines Dover today. The Admiralty Harbour became an important naval anchorage and co-existed with expanded commercial facilities; administrative papers relating to tenders, extensions of time and arbitration survive in the S. Pearson & Son archive.[18][16][13][17]

Great Northern and City Railway

S. Pearson & Son took over construction of the deep-level Great Northern and City Railway between Moorgate and Finsbury Park; the tunnels were under construction by November 1901, and the line opened on 14 February 1904, with intermediate stations at Old Street, Essex Road, Highbury & Islington and Drayton Park.[19][20][21] The company operated independently in its early years and was later acquired by the Metropolitan Railway in 1913.[22] The route remains in passenger use today as the Northern City Line, a National Rail link owned by Network Rail and worked by Great Northern between Moorgate and Finsbury Park.[23][24]

East River tunnels

Blackwall’s record helped Pearson secure the East River Tunnels for the Pennsylvania Railroad in New York. The construction used the same shield tunnelling technique used for Blackwall.[25] The work formed the East River Division of the New York Tunnel Extension. As the railroad’s chief engineer Alfred Noble recorded, S. Pearson & Son “was the only bidder having such an experience and record in work in any way similar to the East River tunnels” and had “built the Blackwall tunnel within the estimates of cost”. The railroad signed on 7 July 1904 with S. Pearson & Son, Incorporated, a New York corporation formed to carry out the contract.[25]

The four single-track tubes opened with Pennsylvania Station in 1910 and remain in intensive use today for Long Island Rail Road and Amtrak services as part of the Northeast Corridor, “the busiest passenger rail line in the United States”. They carry more than 450 Amtrak, LIRR and NJ Transit trains each day.[26]

Construction in Mexico

Mexico became S. Pearson & Son’s largest theatre of operations before the First World War. From 1889 the firm won a sequence of major federal contracts under Porfirio Díaz that ranged from metropolitan drainage to railway rebuilding and new deep-water ports on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Historians note that Díaz and his ministers looked to a British contractor both to balance U.S. influence and to signal reliability to London capital markets, helping to mobilise overseas finance for Mexican public works.[27]

The Gran Canal del Desagüe

The Gran Canal del Desagüe was the firm’s first major Mexican award (1889) and formed part of the long-running and historic drainage of the Valley of Mexico. Pearson’s engineers executed large-scale cuttings, culverts and pumping installations to move floodwater and sewage out of the Valley of Mexico towards outfalls beyond Mexico City. The canal was inaugurated by Díaz in 1900 and has been described by contemporaries and later scholars as one of the emblematic achievements of Porfirian modernity, establishing Pearson’s reputation for managing complex, multi-year works with imported plant and a large workforce.[28][29] The total value for the contract was £2 million.[30]

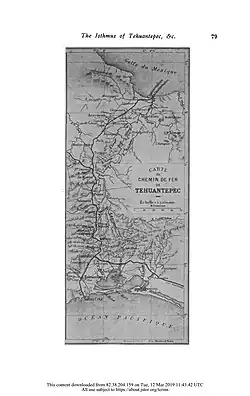

Tehuantepec National Railway

Pearson's next project was the Tehuantepec National Railway, the trans-isthmian line linking Coatzacoalcos on the Gulf to Salina Cruz on the Pacific. Awarded at the end of the 1890s, the programme involved relaying and regrading the 309 km route, renewing bridges and alignments, and constructing supporting depots and workshops. The modernised line formed the land spine of a state-backed interoceanic route and was brought into service alongside new port facilities in 1907.[28][31] The total value of the contract was £2.5 million.[30]

Ports at Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz

In parallel, S. Pearson & Son constructed deep-water ports at Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz, inaugurated in 1907. The works combined heavy dredging, long breakwaters and wharves to create sheltered harbours able to turn ocean-going traffic from both oceans.[28]

Works in Veracruz

The firm also executed major works in the state and port of Veracruz. In 1895 the federal government awarded S. Pearson & Son the modernisation of the harbour, a multi-year programme that followed earlier breakwater construction and introduced dredged channels, protective works and expanded berthing.[32] The harbour contract ran to 1903 at a value of £3 million.[30] Pearson also undertook a companion drainage scheme for the city, 1901 to 1903, contracted by the state government and valued at £400,000.[30]

Sennar Dam

In 1922, S. Pearson & Son was one of six British firms invited to tender to complete Sudan's Sennar Dam and connecting canals. Pearson won the contract to complete the dam by July 1925.[33] Oswald Longstaff Prowde was resident engineer and John Watson Gibson was site agent.[34] Work began in December 1922 and the dam was finished in May 1925.[34]

Oil in Mexico

Land acquisition and early failure

In 1901, during one journey to Mexico, Pearson missed a rail connection in Laredo, Texas, where the town was “wild with the oil craze” after the discovery at Spindletop. That night he investigated reports of natural oil seepages in Mexico and decided to acquire oil prospects that could fuel the Tehuantepec line.[35]

Pearson invested ahead of production in refining and transport from 1905, including Mexico’s first refinery at Minatitlán in 1906.[36] Early test drilling brought little success. In June 1908 a large strike burned for weeks and destroyed the field. Pearson later reflected: “I entered lightly into the enterprise, not realising its many problems... Now I know that it would have been wise to surround myself with proved oil men.”[37]

Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company

Pearson incorporated the Compañía Mexicana de Petróleo “El Águila” on 31 August 1908; in 1909 the company absorbed S. Pearson & Son’s oil properties and operating assets, consolidating lands, wells, refining and transport under a dedicated vehicle.[38][39]

Pearson strengthened exploration by hiring the young American geologist Everette Lee DeGolyer in 1909 to lead geological work for Mexican Eagle. Drilling moved to an area between Veracruz and Tampico and Potrero del Llano No. 4 well was completed in December 1910, which became one of the era’s most publicised gushers, “flowing over 100,000 bbls. of oil a day into the air.”[40] Over its life the Potrero del Llano No. 4 well yielded more than 100 million barrels of oil.[37]

Contemporary and later accounts credit DeGolyer with choosing the site for the Potrero del Llano No. 4 well.[41] However, later scholarship qualifies how much personal credit he should receive for Potrero No. 4, noting that “the geological assessment at Potrero del Llano contributed in only a limited way to the successful location of well #4.” [42]

The Mexican Revolution from 1910 disrupted politics but output grew nonetheless. By 1914 the Pearson group held concessions over roughly 1.5 million acres, operated about 175 miles of pipeline, maintained storage for 7 million barrels and, with a new plant at Tampico, ran two major refineries.[37] In the same year Mexican Eagle accounted for about 60 percent of national output.[43]

Pearson declined approaches from the Texas Company in 1911, Royal Dutch Shell in 1912–1913 and Standard Oil of New Jersey in 1913 and 1916; the British government later restricted transfers in 1917 for wartime reasons.[37] He also founded the Anglo-Mexican Petroleum Company in 1912 to market outside Mexico.[37]

Eagle Oil Transport Company

To carry El Águila export cargoes, Pearson founded the Eagle Oil Transport Company in early 1912 to build and operate a dedicated tanker fleet. Contemporary reports announced a plan to form a five-million-dollar line to “build [a] fleet to carry Mexican oil products”; orders followed for modern steam tankers from British yards to integrate production, storage and ocean transport with the group’s ports at Coatzacoalcos and Tampico.[44][37] During the First World War many Eagle tankers were taken up for Admiralty service, and several were lost to mines and submarines, including SS San Wilfrido, sunk by a German mine near Cuxhaven on 3 August 1914 (one day before Britain entered the war), which contemporary summaries list among the earliest British merchant-ship losses connected with the conflict. [45] The company later used the name Eagle Oil and Shipping Company.[46]

Management and operations in Mexico

Pearson’s own view of management was unapologetically directive. One of Pearson's maxims was “No business can be a permanent success unless its head be an autocrat… the more disguised by the silken glove the better.”[47] During the revolution, management was required to continually bargain with military factions, and have been described as “veritable diplomats” who kept pipelines moving and the refineries guarded with the assistance of the Royal Navy.[48] For administrative and professional staff in the capital, the firm used an early multifamily complex in La Condesa, Mexico City, known as the Edificios Condesa (built in 1911 with 216 apartments).[49] Labour relations did periodically break down, including around Tampico in 1915–1916, with Pearson's companies facing strikes; demands reported at the time included a 25% pay increase and that strikers not face dismissal, and four strike leaders were subsequently jailed.[50]

Sale to Royal Dutch Shell

Wartime controls under the Defence of the Realm Acts blocked any transfer of Pearson’s oil interests in 1917; talks resumed after the Armistice. In October 1918 Calouste Gulbenkian proposed that the Shell group should acquire a stake large enough to secure managerial control, while leaving Pearson with a residual holding “of small moment,” which would “leave Lord Cowdray with a perfect peace of mind”.[51]

A contract signed in March 1919 gave Royal Dutch-Shell 35 per cent of the ordinary capital of Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company and 50 per cent of Anglo-Mexican Petroleum Company for £7.7 million, together with the right to nominate sufficient directors to control both boards for twenty-one years.[52] An option to buy a further 125,000 Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company shares was exercised in January 1920, after which Royal Dutch-Shell and S. Pearson & Son each held about 600,000 shares.[53] Pearson’s private correspondence recorded regret at the sale. Writing to Sir John Cadman on 27 March 1919, he expressed “great regret” at having “to dispose of the bulk of my interest in El Águila'’,” arguing that official policy had prevented an all-British solution.[53][54] In explaining why the government refused to buy into an all-British solution, Sir John Cadman told Pearson that the proposal had been considered “very carefully and sympathetically,” but that it would have been “most undesirable to invest a large sum of Government money in Mexico, primarily on account of the political conditions in that country but also because of the exception which would have been taken to such a step by the United States”.[52]

El Águila remained prominent until 18 March 1938, when President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalised foreign oil assets to form Pemex.[55]

War work and the Air Board (1916–1917)

During the First World War S. Pearson & Son undertook government “war works”, including construction at HM Factory, Gretna, and facilities for tank assembly at Châteauroux.[56] On 3 January 1917 Pearson was appointed (unpaid) President of the Air Board in David Lloyd George’s administration, tasked with coordinating the needs of the Royal Flying Corps and Royal Naval Air Service and advising on aircraft supply and policy.[57] Public pressure after the first large daylight Gotha raid on London on 13 June 1917 (162 killed; 432 injured) accelerated calls for reform.[58] General Jan Smuts’s report to the War Cabinet (17 August 1917) recommended a separate air service and a ministry to direct it; the Air Force Bill received Royal Assent on 29 November and the Air Ministry followed on 2 January 1918.[59] Pearson’s tenure ended when the Air Board was superseded on 26 November 1917; peers recorded appreciation for his service upon his departure.[60]

Business reorganisation (1919–1927)

Transformation into a conglomerate

Between 1919 and 1922 Pearson reorganised his post-El Águila interests around a City finance and holding structure. As one account put it, he “restructured his various businesses, ‘transforming his organization into a great Investment Trust controlling and directing numerous enterprises at home and abroad.’”[5]: 141 In 1919 the group created Whitehall Trust Ltd. as a finance and issuing house with Sir Robert Kindersley as chairman, and designated Whitehall Securities Corporation Ltd. (formed 1907) as the holding company for non-construction assets.[61][8]

By the end of Pearson’s life the group had been reshaped around investment and publishing alongside residual petroleum and utility interests. The construction arm was wound down in the late 1920s, marking a pivot toward finance and media under his successors.[62]

Electric Utilities

In 1906, Pearson had founded the Anglo-Mexican Electric Company Ltd to supply electricity to the tramway of Veracruz. In 1920, Pearson acquired electricity assets in Chile; Whitehall Electric Investments Ltd. was organised to hold these stakes. They were sold to American & Foreign Power in 1929 for £2.7 million.[63]

Petroleum investments

Whitehall Petroleum Corporation Ltd. was formed in 1919 to manage residual oil interests and seek new prospects following the sale of Mexican Eagle.[64] Pearson’s post-1919 entry into the United States took the form of the Amerada Corporation, organised in 1919; its principal operating subsidiary, Amerada Petroleum Corporation, was incorporated in 1920.[65][66] Its first president was Everette Lee DeGolyer, formerly chief geologist at Mexican Eagle.[67][68] Amerada later combined with Hess Oil & Chemical in 1969 to form Amerada Hess Corporation, the forerunner of today’s Hess Corporation.[69]

Lazard Brothers

Seeking a permanent City foothold, in 1920 S. Pearson & Son purchased 40 per cent of Lazard Brothers & Co. from the French partners, taking English ownership of the London accepting house to 53 per cent and aligning Lazard with the group’s issuing activity.[4] A Bank of England–supervised rescue in 1931 increased the family holding to about 80 per cent, an episode carried through by his successors.[70]

Newspapers

Pearson also expanded in newspapers: he first invested in The Westminster Gazette in 1908 as part of a Liberal syndicate led by Alfred Mond and Sir John Brunner, then assumed full control after the war and relaunched the paper as a national morning title on 5 November 1921. Despite a circulation boost the paper made continued losses and ceased on 31 January 1928, merging the next day with the Daily News as the Daily News and Westminster Gazette. Around the Gazette he consolidated provincial titles that became the nucleus of Westminster Press, laying groundwork for the organisation’s later publishing focus.[71] d ===Coal===— In heavy industry, Pearson partnered with Dorman Long in 1922 to develop the Kent coalfield through Pearson & Dorman Long Ltd. The scheme aimed at a coal–iron–steel base in east Kent but met labour and geological difficulties: Snowdown Colliery was modernised from 1924, and sinking at the Betteshanger Colliery began in 1924 to secure high-temperature coal suitable for steelmaking. Miners’ housing was provided at Aylesham via a public-utility society—Aylesham Tenants Ltd—established with Eastry Rural District Council in 1926 for an initial programme of about 1,200 homes; Kent County Council joined in 1927.[72][73][74][75]

Political career

Pearson was created a Baronet, of Paddockhurst, in the Parish of Worth, in the County of Sussex, and of Airlie Gardens, in the Parish of St Mary Abbots, Kensington, in the County of London, in 1894.[76] He was first elected Liberal Member of Parliament for Colchester at a by-election in February 1895.[77] He held the seat at the 1895 general election and retained it until 1910,[78] when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Cowdray, of Midhurst in the County of Sussex.[79] In January 1917 he was sworn of the Privy Council[80] and made Viscount Cowdray, of Cowdray in the County of Sussex.[81] He served as President of the Air Board in 1917 (see War work and the Air Board).[82]

Political views and reputation

Pearson’s business commitments in Mexico shaped his public identity. During and after his tenure as Liberal MP for Colchester (1895–1910) he was frequently dubbed the “Member for Mexico”, a phrase biographers and historians have used to reflect the centrality of his Mexican contracting and oil interests and his extended periods abroad.[83][84]

His own public statements outlined a reformist, paternalist view of industrial relations. In a 1920 address as Rector of the University of Aberdeen he argued that an “ideal wage” should keep workers “in health and efficiency, with a margin for recreation and saving”, and proposed a mix of guaranteed minimum pay, piecework with a minimum, profit-sharing bonuses, national unemployment insurance, and worker participation in management; he also supported public control (ownership where necessary) of natural monopolies.[85] In the same period he styled himself a “day-by-day worker” and referred to his personal motto “Do it with thy might”, a phrase also carved at Cowdray Park.[86][87]

Contemporary obituaries emphasised his organisational ability and public service, describing him as a “great captain of industry”.[88]

Philanthropy

Cowdray and his wife, Annie Pearson, Viscountess Cowdray (née Cass), were major benefactors of education, health and nursing. Lady Cowdray was closely identified with the professionalisation of British nursing and was widely described as the “fairy godmother of nursing”.[89]

In 1920, Lady Cowdray bought 20 Cavendish Square for the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and in 1921–22 funded rebuilding along Henrietta Street to create expanded headquarters; in 1922 she founded the adjacent British Cowdray Club (originally named the Nation’s Nurses and Professional Women’s Club).[90][91] The RCN’s main assembly space, Cowdray Hall, continues to commemorate the family; the hall retains stained glass by Dudley Forsyth and a carved Cowdray coat of arms.[92]

In Mexico City the couple financed the Cowdray Sanatorium (later the “English Hospital”), which opened in 1923 and ultimately formed part of the American British Cowdray (ABC) Medical Center; contemporary accounts record a pledge of around one million gold pesos.[93][94] The commemoration continues in the hospital’s Torre de Cuidados Críticos y Quirúrgicos Annie Cass (Annie Cass Surgical and Critical Care Tower) at the Observatorio campus, opened in the late 2010s.[95][96]

Pearson made large personal donations in Britain during and after the First World War. In October 1918 he gave £100,000 to establish the Royal Air Force Club, subsequently acquiring premises at 128 Piccadilly and 6 Park Lane for the Club; he also contributed to the RAF Memorial Fund.[97] Further gifts included £50,000 to the League of Nations Union and £10,000 to University College London, noted in contemporary obituaries.[88]

In higher education he endowed Spanish studies at the University of Leeds in 1916, creating the Cowdray Professorship and a programme to deepen Anglo–Mexican academic links; Lady Cowdray’s later gifts supported nursing scholarships administered through the College and its charitable successors.[98][99][89]

In Aberdeen, Lady Cowdray funded the creation of the Cowdray Hall as a daytime concert venue adjoining the Aberdeen Art Gallery; it was opened by George V and Queen Mary on 25 September 1925 “with a view to encouraging the taste for art and music”.[100][101] Contemporary obituaries also recorded “many benefactions” by the Cowdrays to Aberdeen’s public institutions and noted that the city had arranged to confer the freedom of the city upon Pearson shortly before his death.[102]

Marriage and children

Lord Cowdray married Annie Cass. They had four children:[103]

- Weetman Harold Miller Pearson, 2nd Viscount Cowdray

- Hon. Bernard Clive Pearson (12 August 1887 – 22 July 1965), later chairman of S. Pearson & Son and a backer of British civil aviation in the 1930s.[104]

- Hon. Francis Geoffrey Pearson (23 August 1891 – 6 September 1914), who on 6 August 1909 married Ethel Elizabeth Lewis. At the start of World War I he served as a motorcycle courier with the BEF and died after capture near Varreddes during the German advance on Paris; he is buried at Montreuil-aux-Lions British Cemetery.[105] Reports at the time alleged he was treated with brutality by his captors, directly causing his death; Arthur Conan Doyle referred to him as “the gallant motor-cyclist, Pearson” in the 1914 essay “A Policy of Murder.”[106]

- Gertrude Mary Pearson (GBE), who married Thomas Denman, 3rd Baron Denman, later Governor-General of Australia.[107]

Death

Lord Cowdray died in his sleep at Dunecht House, Aberdeenshire, on 1 May 1927, aged 70.[88] He was succeeded by his eldest son Weetman Harold Miller Pearson, 2nd Viscount Cowdray.[108]

Legacy

Wealth

By 1919 the Pearson group ranked as the largest British enterprise by stock-market value. A contemporaneous reconstruction places the “Pearson Group” at about £79 million, ahead of Burmah Oil, J. & P. Coats, Anglo-Persian Oil Company and Lever Brothers.[109][110][111] Pearson’s personal estate proved at death in 1927 was reported at about £4 million.[88]

S. Pearson & Son in the 20th century

After Pearson’s death in May 1927, his successors navigated a Bank of England–supervised rescue of Lazard Brothers in 1931; as part of the arrangements the Pearson family’s holding in the London house rose to about 80 per cent.[112] Under Bernard Clive Pearson in the 1930s, Whitehall Securities became a leading investor in civil aviation, backing the consolidation that produced British Airways Ltd in 1935 and investing in associated suppliers.[113] Pearson plc exited banking through two 1999–2000 transactions, agreeing the sale of its Lazard interests in June 1999 for £410 million and completing the disposal on 3 March 2000 for total proceeds of £436 million, including dividends.[114][115]

Tehuantepec railway

In 2019 the Government of Mexico created the Interoceanic Corridor of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (CIIT) by decree, to rehabilitate and integrate the railway and ports between Salina Cruz and Coatzacoalcos—infrastructure first developed at scale by Pearson’s organisation in the early 20th century. The first rehabilitated freight line between the two ports was inaugurated in December 2023, linking a new logistics corridor to Pearson-era routes and is now known as Line Z (Tren Interoceánico).[116]

Pearson plc in the 21st century

In the 21st century Pearson plc refocused on education, disposing of major media holdings to concentrate on digital learning: it agreed the sale of the FT Group to Nikkei for £844 million (July 2015), sold its 50% stake in The Economist Group for £469 million (October 2015), and completed the sale of its remaining 25% of Penguin Random House to Bertelsmann (announced December 2019; completed April 2020).[117][118][119][120]

Estates

.jpg)

Pearson channelled part of his wealth into country-house projects and conservation. He purchased Cowdray Park in 1909 and sponsored stabilisation and archaeological work on the nearby Tudor Cowdray Ruins before the First World War.[2][121] In Scotland he leased Dunecht House from 1907 and purchased it in 1912, commissioning Sir Aston Webb to carry out major extensions and terraces between 1913 and 1920.[122] He also owned Paddockhurst in Sussex (later Worth Abbey and Worth School), reflected in the territorial designation of his 1894 baronetcy; the estate saw significant Edwardian alterations under his ownership.[123]

Arms

|

|

References

- ^ Spender, J. A., Weetman Pearson; First Viscount Cowdray (London: Cassell, 1930), pp. 2, 272.

- ^ a b "Cowdray Park, Easebourne, West Sussex". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Garner 2011, pp. 141–142, 157–163.

- ^ a b O’Sullivan, Brian (2018). From Crisis to Crisis: The Transformation of Merchant Banking, 1914–1939. Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 382. ISBN 9783319966977.

- ^ a b Hausman, William J.; Hertner, Peter; Wilkins, Mira (2008). Global Electrification: Multinational Enterprise and International Finance in the History of Light and Power, 1878–2007. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780521888943.

- ^ Burke's Peerage, 106th ed., p. 688.

- ^ Garner 2011, pp. 38–41.

- ^ a b "Records of S. Pearson & Son c. 1870–1955" (PDF). Science Museum Group Archives. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Southern gatehouse to the Blackwall Tunnel (List Entry 1212100)". Historic England. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

The tender of S Pearson and Son … was accepted towards the end of 1891 … The Blackwall Tunnel was opened by the Prince of Wales on 22 May 1897.

- ^ a b c Thom, Cathy (1994). "The Blackwall Tunnel" (PDF). Survey of London. British History Online. pp. 367–372. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Northern portal and parapet to the Blackwall Tunnel (List Entry 1065070)". Historic England. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Admiralty Pier 1847–1893". Dover Museum. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

Plans included a 2,000 feet extension of Admiralty Pier, an Eastern arm of 2,900 feet and a breakwater of 4,200 feet … enclosing 610 acres (Admiralty) and 68 acres (commercial).

- ^ a b "The Admiralty Harbour". Annals of Dover (1916). Dover.uk.com. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "EASTERN ARM, DOVER HARBOUR (List Entry 1393604)". Historic England. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

Constructed of concrete blocks of 26 to 42 tons each, faced above sea level with granite.

- ^ "Admiralty Pier Part II (from 1909)". The Dover Historian. 6 June 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

Staging was erected and rails laid for Goliath cranes that lowered the concrete blocks into place. Titan cranes later replaced them.

- ^ a b "Records of S. Pearson & Son c. 1870–1955" (PDF). Science Museum Group Archives. pp. 28–31. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ a b Winchester, Clarence. "Building Dover Harbour". Wonders of World Engineering. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Admiralty Pier (MKE14504)". Exploring Kent’s Past. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Moorgate Station". Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

In November 1901… tunnels then under construction between Finsbury Park and Moorgate.

- ^ Halliday, Stephen (2001). Underground to Everywhere: London's Underground Railway in the Life of the Capital. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 075092585X.

- ^ "Moorgate Station". Heritage Gateway. Historic England. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Moorgate Station". Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Launching Britain's first signals-free commuter railway". Network Rail. 19 May 2025. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

The Northern City Line between Finsbury Park and Moorgate has become the first commuter railway in Britain to run without signals beside the track.

- ^ "Journey information from Moorgate to Finsbury Park". Great Northern. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b Noble, Alfred (September 1910). "The New York Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad: The East River Division". Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers. 68. American Society of Civil Engineers: 63–74. Retrieved 12 August 2025 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "East River Tunnel Rehabilitation Project" (PDF). Amtrak. January 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

The ERT system opened in 1910… [and] is a critical piece of the NEC, the busiest passenger rail line in the United States. Used by more than 450 daily Amtrak, Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and NJ TRANSIT trains.

- ^ Garner 2011, pp. 10–15, 24–25, 69–70.

- ^ a b c "Records of S. Pearson & Son c. 1870–1955" (PDF). Science Museum Group Archives. pp. 28–37. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Leal Cázares, Irma Elizondo (2018). "Análisis histórico-crítico del sistema de desagüe en la Ciudad de México". Arquitectura, Ciudad y Entorno (in Spanish). 13 (38): 53–78. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

…el Gran Canal del Desagüe… fue considerado uno de los mayores logros de la modernidad porfiriana.

- ^ a b c d Garner 2011, pp. 241.

- ^ Garner 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Garner 2011, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Winchester, Clarence (1938). "Conquest of the Desert". Wonders of World Engineering. pp. 289–295. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b "The Sennar Dam and the Gezira Irrigation Scheme" (PDF). The Engineer. 26 September 1924. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Yergin, Daniel, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), pp. 230–232.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan C. (1993). Oil and Revolution in Mexico: The Politics and Formation of a National Industry. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780520079342.

- ^ a b c d e f Godley, Andrew; Bud-Frierman, Lisa; Wale, Judith (2007). "Weetman Pearson in Mexico and the Emergence of a British Oil Major, 1901–1919". Economics Discussion Papers. University of Reading. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Jiménez Aguirre, Lucila (2012). Origen del petróleo en México y su legado fotográfico. Wilfrid S. Sellar y Otis A. Aultman (Master's thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez / UTEP. pp. 66–67. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "La herencia petrolera: historia de PEMEX" (PDF). Boletín 19, Petróleo y Nación (in Spanish). Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX): 24–26. 2004. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "To de Potrero del Llano, Pozo No. 4, 1910". DeGolyer Library Digital Collections. Southern Methodist University. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

After the well was completed in December, 1910, it ran wild for three months, flowing over 100,000 bbls. of oil a day into the air.

- ^ Weaver, Bobby D. (15 January 2010). "DeGolyer, Everette Lee". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

In 1910 he was responsible for locating the Potrero del Llano Number Four for El Aguila oil company, which opened a new major oil field in Mexico.

- ^ Gerali, Francesco; Riguzzi, Paolo (2017). "Gushers, science and luck: Everette Lee DeGolyer and the Mexican oil upsurge, 1909–19". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 442: 413–424. doi:10.1144/SP442.37.

the geological assessment at Potrero del Llano contributed in only a limited way to the successful location of well #4.

- ^ Haber, Stephen; Razo, Armando; Maurer, Noel (2003). The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780521820677.

- ^ "Form $5,000,000 Line; Cowdray Interests to Build Fleet to Carry Mexican Oil Products". The New York Times. 29 February 1912.

- ^ "San Wilfrido (1914)". Tyne Built Ships. Retrieved 12 August 2025."British Merchant Ships Attacked, 1914". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "Eagle Oil and Shipping Company". Benjidog Ship Histories. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Spender, J. A. (1930). Weetman Pearson, First Viscount Cowdray, 1856–1927. London: Cassell.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan C. (1993). Oil and Revolution in Mexico: The Politics and Formation of a National Industry. University of California Press. pp. 197, 206. ISBN 9780520079342.

- ^ González Alvarado, Rocío (30 October 2011). "Festejan centenario del edificio Condesa, reducto del barrio". La Jornada (in Spanish).

En sus orígenes, el inmueble… fue ocupado por europeos de "familias acomodadas", que laboraban en la compañía petrolera El Águila.

"Condesa" (PDF). Alcaldía Cuauhtémoc (in Spanish). 2021. pp. 28–29.Consta de cuatro inmuebles, con un total de 216 departamentos.

"El DF, a 190 años". Obras Expansión (in Spanish). 2 October 2015. - ^ Brown, Jonathan C. (1993). Oil and Revolution in Mexico: The Politics and Formation of a National Industry. University of California Press.

- ^ Garner 2011, p. 226.

- ^ a b Garner 2011, pp. 226–227.

- ^ a b Garner 2011, p. 227.

- ^ Contemporary reporting described the transaction as a “$75,000,000 oil deal,” a headline figure reflecting the scale and valuation of the assets involved rather than Pearson’s initial cash receipt. "$75,000,000 Oil Deal; Royal Dutch and Shell Companies Buy Mexican Eagle Stock". The New York Times. 15 March 1919. p. 23. Scholarly accounts also note that Pearson’s total proceeds were higher than the initial £7.7 million once follow-on elements of the deal were included. Bud-Frierman, Lisa; Godley, Andrew; Wale, Judith (2010). "Weetman Pearson in Mexico and the Emergence of a British Oil Major, 1901–1919". Business History Review. 84 (2): 275–300. doi:10.1017/S0007680500002610..

- ^ Haber, Stephen; Razo, Armando; Maurer, Noel (2003). The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 198. ISBN 9780521820677.

- ^ "Records of S. Pearson & Son c. 1870–1955" (PDF). Science Museum Group Archives. p. 25. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Air Board — debate". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commons. 26 April 1917.

- ^ "Air Raid: The Tragedy of Upper North Street School". Historic England – Heritage Calling. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Report by General Smuts on Air Organisation and the Direction of Aerial Operations (17 Aug. 1917)". Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Lords Chamber (21 Nov. 1917)". Hansard. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "War, the First Nationalization, Restructuring and Renewal, 1914–1929 (chapter PDF)" (PDF). Cambridge University Press (Global Electrification). 2008. p. 165. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

In 1919, his firm set up Whitehall Trust Ltd. as a finance and issuing house; Kindersley was appointed chairman.

- ^ Garner 2011, pp. 230–233.

- ^ Hausman, William J.; Peter Hertner; Mira Wilkins (2008). Global Electrification: Multinational Enterprise and International Finance in the History of Light and Power, 1878–2007 (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 165.

- ^ "Letter from Whitehall Petroleum Corp. Ltd to Lloyd's Register (1920–1923)". Lloyd’s Register Foundation Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Amerada Corporation records, 1919–1970 — DeGolyer Library". Southern Methodist University. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "History of Amerada Hess Corporation". FundingUniverse. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Bud-Frierman, Lisa; Godley, Andrew; Wale, Judith (Summer 2010). "Weetman Pearson in Mexico and the Emergence of a British Oil Major, 1901–1919". Business History Review. 84 (2): 275–300. JSTOR 20743905.

- ^ Garner 2011, p. 228.

- ^ "Hess Corporation — company overview". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 18 July 2025. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ "History — 1931". Lazard. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "The Westminster gazette". Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Became a national morning newspaper with Nov. 5, 1921 issue … Merged with: Daily news … to form: Daily news and Westminster gazette.

- ^ "Appendix 1: Theme 10.1 – The East Kent Coalfields" (PDF). Dover District Council. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Snowdown Colliery". Dover Museum – Coalfield Heritage Initiative Kent. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Betteshanger Colliery". Dover Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Aylesham and the Planning of the East Kent Coalfield (Part I)". Municipal Dreams. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "No. 26526". The London Gazette. 26 June 1894. p. 3652.

- ^ F. W. S. Craig, British Parliamentary Election Results 1885–1918. Macmillan, 1974, p. 98.

- ^ Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs – Constituencies beginning with "C" (part 5)

- ^ "No. 28398". The London Gazette. 22 July 1910. p. 5269.

- ^ "No. 29920". The London Gazette. 26 January 1917. p. 947.

- ^ "No. 29924". The London Gazette. 30 January 1917. p. 1053.

- ^ "Air Board — debate". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commons. 26 April 1917.

- ^ Young, Desmond (1966). Member for Mexico: A Biography of Weetman Pearson, First Viscount Cowdray. London: Cassell.

- ^ Garner 2011, p. 45.

- ^ Pearson, Weetman D. (November 1920). "Labour—Its Problems and the Ideal Wage". The Aberdeen University Review. 8 (22): 1–12. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

The ideal wage should be sufficient to maintain the worker in health and efficiency, with a margin for recreation and saving. … Broadly stated, the methods I advocate are: first, the guaranteed minimum; … piecework with a guaranteed minimum; and a bonus on profits; … unemployment insurance on a national basis; … and public control—ownership where necessary—of natural monopolies.

- ^ Pearson, Weetman D. (November 1920). "Labour—Its Problems and the Ideal Wage". The Aberdeen University Review. 8 (22): 1–2. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ a b "Cowdray Park (Official List Entry)". Historic England. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

The north wall is dominated by the stone fireplace inserted by the first Viscount in 1909. It includes Pearson's heraldry and the family motto 'Do it with thy might' carved in relief.

- ^ a b c d "Lord Cowdray: A Great Captain of Industry". The Times. No. 44570. 2 May 1927. p. 16. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ a b "Honour Roll — Lady Cowdray". RCN Foundation. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Often referred to as the 'Fairy Godmother of Nursing' … in the early 1920s Lady Cowdray donated 20 Cavendish Square to the RCN for its headquarters.

- ^ "Cavendish Square 4: No. 20 (the Royal College of Nursing)". Survey of London (UCL). 29 April 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Cavendish Square". Survey of London (UCL). 13 October 2017. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Annie Pearson, Viscountess Cowdray, bought 20 Cavendish Square … and in 1921–2 funded rebuilding … as headquarters for the College of Nursing.

- ^ "Cowdray Hall — 20 Cavendish Square". 20 Cavendish Square (Royal College of Nursing). Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Vázquez, María F. (2012). "Historia del Centro Médico ABC" (PDF). Anales Médicos (ABC) (in Spanish). 57 (1): 68–78. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Institutional history". Centro Médico ABC. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Nuestras ubicaciones — Observatorio". Centro Médico ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Estacionamiento — Torre de Cuidados Críticos y Quirúrgicos Annie Cass.

- ^ "Guía para familiares y visitantes". Centro Médico ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Torre de Cuidados Críticos y Quirúrgicos Annie Cass.

- ^ "Club History". Royal Air Force Club. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "A life less ordinary: Lord Cowdray and the making of modern Mexico". University of Leeds. 5 October 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Taylor, Jack (2022). "Developments in the Modern Languages in the University of Leeds during the First World War". Language & History. 65 (1): 45–66. doi:10.1080/0078172X.2022.2041946.

- ^ "Cowdray Hall". Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums (Aberdeen City Council). Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Guide to the Revitalised Museum Project (PDF). Scottish Society for Art History. July 2020. pp. 10–11. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Cowdray Hall (1925), funded by Annie, Viscountess Cowdray, as a venue for day-time concerts, "with a view to encouraging the taste for art and music."

- ^ "Lord Cowdray: A Great Captain of Industry". The Times. No. 44570. 2 May 1927. p. 16. Retrieved 11 August 2025 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ Burke's Peerage, 106th ed., p. 688.

- ^ Davies, R. E. G. (2005). British Airways: An Airline and its Aircraft, Volume 1: 1919–1939. McLean, Virginia: Paladwr Press. pp. 74–104. ISBN 1-888962-24-0.

- ^ "The Hon Francis Geoffrey Pearson". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Arthur Conan Doyle (1914). "The German War — VI. A Policy of Murder". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

…the death of the gallant motor-cyclist Pearson, the son of Lord Cowdray.

- ^ "Denman [née Pearson], Gertrude Mary, Lady Denman (1884–1954)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Burke's Peerage, 106th ed., p. 688.

- ^ Bud-Frierman, Lisa; Godley, Andrew; Wale, Judith (2010). "Weetman Pearson in Mexico and the Emergence of a British Oil Major, 1901–1919". Business History Review. 84 (2): 275–300. JSTOR 20743905.

Table of Britain's largest industrial enterprises in 1919 headed by the Pearson Group (approx. £79m).

- ^ Godley, Andrew; Casson, Mark (2010). "History of Entrepreneurship: Britain, 1900–2000". In Landes, David S.; Mokyr, Joel; Baumol, William J. (eds.). The Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times. Princeton University Press. p. 252. ISBN 9781400833580.

Table of the twelve largest British companies in 1919, led by Weetman Pearson's group.

- ^ Jones, Geoffrey (2015). Business Groups Exist in Developed Markets Also: Britain as an Irregular Case (PDF) (Report). Working Paper 16-066. Harvard Business School.

A recent study has estimated the market value of the entire group in 1919 at £79 million, which would have made it Britain's largest business.

- ^ "History — 1931". Lazard. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Davies, R. E. G. (2005). British Airways: An Airline and its Aircraft, Volume 1: 1919–1939. McLean, Virginia: Paladwr Press. pp. 74–104. ISBN 1-888962-24-0.

- ^ Barrie, Chris; Jill Treanor (25 June 1999). "Pearson offloads Lazard stake for £410m". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ Annual Report and Accounts 2000 (Report). Pearson plc. 2001. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

On 3 March 2000 completion of the Lazard disposal brought total proceeds of £436m, comprising £40m dividends and £396m sale proceeds.

- ^ "Passenger operations begin on isthmus of Tehuantepec railway". 9 January 2024. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Pearson to sell FT Group to Nikkei Inc". Financial Times – Press release. 23 July 2015. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Press Release: Full year 2015 results" (PDF). Pearson plc. 26 February 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

…completed the sale of our 50% stake in The Economist Group on 16 October 2015 for £469m.

- ^ "Bertelsmann acquires full ownership of Penguin Random House". Penguin Random House (corporate). 18 December 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Bertelsmann Completes Full Acquisition of Penguin Random House" (PDF). Bertelsmann. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "Cowdray Ruins History". Cowdray Estate. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Restoration and survey commissioned c.1909–14 under (Sir) William St John Hope.

- ^ "Dunecht House (Listed Building LB3133)". Historic Environment Scotland. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

- ^ "History". Worth School. Retrieved 11 August 2025.

Further reading

- Garner, Paul (2011). British Lions and Mexican Eagles: Business, Politics, and Empire in the Career of Weetman Pearson in Mexico, 1889–1919. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804774451.

- Middlemas, Keith. The Master Builders: Thomas Brassey, Sir John Aird, Lord Cowdray, Sir John Norton-Griffiths. London: Hutchinson, 1964.

- Spender, J. A. Weetman Pearson: First Viscount Cowdray. London: Cassell, 1930.

- Young, Desmond. Member for Mexico: Biography of Weetman Pearson, First Viscount Cowdray. London: Cassell, 1966.

External links

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Viscount Cowdray

- Weetman Dickinson Pearson at Grace's Guide to British Industrial History

- Weetman Dickinson Pearson at the National Portrait Gallery