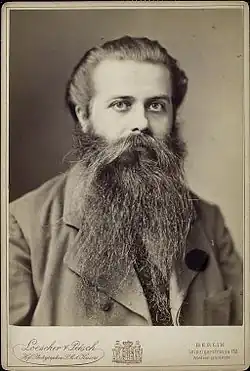

Eduard von Hartmann

Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann (23 February 1842 – 5 June 1906) was a German philosopher, independent scholar and writer. He was the author of the influential Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). Von Hartmann's notable ideas include the theory of the Unconscious and a pessimistic interpretation of the "best of all possible worlds" concept in metaphysics.

Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869)

- If we glance at the judgments of the greatest minds of all ages, we find those, who have at all found occasion to express their opinion on the subject, pronouncing the condemnation of life in very decided terms. Plato says in the “Apology”: “Now, if death is without all sensation, a dreamless sleep, as it were, it would be indeed a wonderful gain. For I think if any one selected a night in which he had slept so soundly as to have had no dream, and then compared this night with the other nights and days of his life, and after serious consideration declared how many days and nights he had spent better and more pleasantly than this one, that not merely an ordinary mortal, but the great king of Persia himself, would find these but few in number as compared with all his other days and nights.” More clearly and picturesquely it would hardly be possible to state the advantage which, on the average, non-being possesses over being.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 613-614 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Kant says (Werke, vii. p. 381): “One must indeed make an ill reckoning of the worth of the journey (of life) if one can still wish that it should last longer than it actually does, for that would only be a prolongation of a perpetual contest with sheer hardships.” Page 393, he calls life “a trial-time, wherein most succumb, and in which even the best does not rejoice in his life.” Fichte declares the natural world to be the very worst that can be, and is himself only consoled by the belief in the possibility of a preferment to the blessedness of a supersensible world through the medium of pure thought. He says (Werke, v. pp. 408–409): “Courageously men betake themselves to the chase after felicity, heartily appropriating and fondly devoting themselves to the first best object that pleases them and that promises to repay their efforts. But as soon as they withdraw into themselves and ask themselves, ‘Am I now happy?’ the reply comes distinctly from the depth of their soul, ‘Oh, no; thou art still just as empty and destitute as before!’ Convinced that this is a true deliverance, they imagine that they have failed only in the choice of their object, and throw themselves upon another. This, too, will just as little content them as the first; no object beneath the sun and moon will satisfy them. . . . Thus they pine and fret their life through; in every situation in which they find themselves, thinking if it were only different how much better their lot would be, and yet, after it has changed, finding themselves no better off than before; at every spot at which they stand, supposing if they could only reach yon height their uneasiness would cease, yet finding again, even on the height, their old woe. . . . Perhaps they even resign the hope of satisfaction in this earthly life, but accept in compensation a certain traditional doctrine concerning a blessedness beyond the grave. In what a deplorable illusion are they caught! Quite certainly, indeed, lies blessedness also beyond the grave for him for whom it has already begun on this side; through the mere interment, however, one does not enter into blessedness; and they will in the future life, and in the infinite series of all future lives, just as vainly seek blessedness as they have sought it in the present life, if they seek it in anything else than in that which already encircles them so closely here that it can never be brought nearer to them in endless time, in the Eternal.—Thus, then, errs the poor offspring of eternity, thrust out of his paternal abode, always surrounded by his celestial heritage, which his timid hand fears only to touch, inconstant, and roaming in the waste, endeavouring in vain to settle; fortunately, through the speedy ruin of all his habitations, reminded that he will nowhere find rest but in his father’s house.”

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 614-615 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Schelling says (Werke, i. 7, p. 399): “Hence the veil of sadness that is spread over all Nature, the deep indestructible melancholy of all life.” He has, moreover (Werke, i. 10, pp. 266–268), a very beautiful passage which should be read in its entirety; here I can only quote a few fragments: “Certainly it is a painful way the Being which lives in Nature traverses in his passage through it; to that the line of sorrow, traced on the countenance of all Nature, on the face of the animal world testifies. … But this misfortune of existence is hereby annulled that it is accepted and felt as non-existence, in that man seeks to bear up in the greatest possible freedom from it. … Who will trouble himself about the common and ordinary mischances of a transitory life that has apprehended the pain of universal existence and the great fate of the whole?” “Anguish is the fundamental feeling of every living creature” (i. 8, 322). “Pain is something universal and necessary in all life. … All pain only comes from being” (i. 8, 335). “The unrest of unceasing willing and desiring, by which every creature is goaded, is in itself unblessedness” (ii. 1, 473; comp. also i. 8, 235–236; ii. 1, 556, 557, 560). I shall content myself with these citations; a few more will be found in Schopenhauer’s “World as Will and Idea,” ii. chap. 46.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 615 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- But what do such subjective expressions of opinion without annexed reasons prove? Must we not rather mistrust them because they proceed from eminent intelligences, affected by that melancholy sadness which is the inheritance of almost all genius, because they do not feel at home in the world of their inferiors? (Comp. Aristotle, Prob. 30, 1.) Certainly the worth of the world must be measured by its own standard, not by that of the genius. Let us look, therefore, further.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 615 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Imagine some one who is no genius, but a man with the best general culture of his time, endowed with all the other good things of an enviable lot, in the most vigorous years of manhood, who is fully conscious of the advantage which he enjoys over the lower orders in the uncivilised nations and over his fellows of ruder ages, and who by no means envies those above him, who are tormented by all sorts of discomforts spared to himself—a man who is neither exhausted and rendered blasé by immoderate pleasure, nor has ever been crushed by exceptional strokes of fate. Let us imagine Death to draw nigh this man and say, Thy life-period is run out, and at this hour thou art on the brink of annihilation; but it depends on thy present voluntary decision, once again, precisely in the same way, to go through thy now closed life with complete oblivion of all that has passed. Now choose!” I question whether the man would prefer the repetition of the past performance to non-existence, if his mind be free from fear, and calm, and if he has not altogether lived so thoughtlessly, without all self-reflection, that, in his inability to offer a summary criticism of the experiences of his life, he does but give expression in his answer merely to the instinct of the desire of living at all cost, or allows his judgment to be thereby too much biassed. How much more, however, now must this man prefer non-being to a re-entrance into life, which offers him not the favourable conditions his past life offered, but, on the contrary, leaves it perfectly to chance into what new life-conditions he enters, which thus offers him, with a possibility bordering on certainty, worse conditions than those which he first disdained!

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 615-616 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Let one consider, further, that the foolish vanity of man goes so far as to prefer to seem rather than to be not merely well but also happy, so that every one carefully hides where the shoe pinches, and tries to make a show of opulence, contentment, and happiness which he does not at all possess.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 619 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Lastly, when we consider, as is a priori to be expected, that the same unconscious will which has created beings with these instincts and passions will also through these instincts and passions influence conscious thinking in the direction of the same life-impulse, we should rather only wonder how the instinctive love of life should come to be able in consciousness to condemn this same life; for the same Unconscious which wills life, and, moreover, for its quite special ends wills just this life in spite of its wretchedness, will certainly not omit to fit out the creatures of life with just as many illusions as they need, in order not merely to make life supportable, but also to leave over enough love of life, elasticity, and freshness for the life-tasks to be accomplished by them and claiming all their energy, and thus to cozen them concerning the misery of their existence.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 619 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- In this sense Jean Paul well says: “We do not love life because it is beautiful, but because we must love it; and hence it happens that we often draw the inverted conclusion: since we love life, it must be beautiful.” What is here called love to life is nothing else but the instinctive impulse of self-preservation, the conditio sine qua non of individuation, the negative expression of which is the avoidance and warding off of disturbances, and in the highest degree the fear of death, of which mention has been made at the beginning of Sect. B. Chap. i. Death in itself is no evil at all, for the pain connected with it falls indeed still into life, and would not be more feared than the same pain in sickness, if the cessation of individual existence were not bound up with it, which is not felt, thus cannot be any evil at all. As little then as the fear of death can be understood otherwise than from the blind instinct of self-preservation, so little the love of life.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 619 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- For if it is true that with the progressive intelligence of the world the illusions of existence also must be more and more undermined, until finally all is recognised as “vanity of vanities,” the condition of the world would become ever more unhappy the more it approaches the goal of its evolution, whence we should conclude that it would have been more rational to prevent the development of the world the earlier the better, best of all to suppress its arising at the moment of its origin.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 621 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- If I have the choice either of not at all hearing, or of hearing first for five minutes discords and then for five minutes a fine piece of music; if I have the choice either not to smell at all, or to smell first a stench and then a perfume; if I have the choice either not to taste, or to taste first something disagreeable and then something agreeable, I shall in all the cases decide for the non-hearing, non-smelling, and non-tasting.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 629 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Finally, also, the competency or assurance against want and privation cannot be regarded as a positive gain or enjoyment, but only as the conditio sine qua non of bare life, which has to wait for its enjoyable fulfilment. To endure hunger, thirst, frost, heat, or damp is painful; protection from these evils by needful dwelling, clothing, and food cannot be called positive good (enjoyment in eating does not belong to this category). Were, namely, the bare life assured in its conditions of existence already a positive good, mere existence in itself must fill and satisfy us. The contrary is the case: the assured existence is a torment, unless a filling up of the same is added. This torment, which is expressed in ennui, may be so insupportable that even pains and ills are welcome to escape it.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 631 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- The most usual filling of life is work. There can be no doubt that work for him who must work is an evil, be it in its consequences for himself, as for humanity and the advancing evolution, ever so rich in blessing; for nobody works who is not compelled, i.e., who does not take work upon himself as the less of two evils—whether the greater evil be want, the torment of ambition, or even mere ennui—or who had not the intention through undertaking this evil to purchase for himself greater positive good (e.g., the satisfaction in rendering life more pleasant for himself and those dear to him, or for the value of the performances produced by means of work). All that can be said on the value of work reduces itself either to economical advantages (with which we shall deal later on), or to the avoidance of greater evils (idleness is the beginning of all vices); and the utmost that man can attain to is, “that he should rejoice in his own works, for that is his portion,” i.e., that he should become habituated to bear the inevitable as well as possible, as the cart-horse at last draws the cart with tolerable good-humour. At work man consoles himself with the prospect of leisure, and in leisure we have to console ourselves with the thought of work. Thus the alternate play of leisure and work comes to this, that the sick turns himself in his bed to get out of his uncomfortable position, but soon finds the new position just as uncomfortable, and so turns back again.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 631-632 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Let us first consider the consequences of love in general. One side generally loves more ardently than the other; the less loving is usually the first to draw back, and the other feels faithlessly abandoned and betrayed. Whoever could see and weigh the pain of deceived hearts on account of broken vows, as much of it as is in the world at any moment, would find that it alone exceeds all the happiness derived from love existing at the same time in the world, for the simple reason that the pain of disillusion and the bitterness of betrayal lasts much longer than the blissful illusion.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 638 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- But let us leave this on one side, and grant that a very strong will, no matter how arisen, to possess the beloved object is consciously present; then undoubtedly must the satisfaction of this will be felt as intense pleasure, and that the more the more clearly the person concerned becomes conscious of the fulfilment of his wish as of a fact dependent on external circumstances; the greater therefore is the contrast of the fulfilment with a preceding recognition of difficulties and obstacles. A caliph, on the other hand, who is conscious that he has only to issue his commands in order to possess any woman that pleases him, will hardly be at all conscious of the satisfaction of his will, however strong it may be in any particular case. Hence it follows, however, that the pleasure of satisfaction is only purchased by preceding pain at the supposed impossibility of attaining possession; for difficulties whose conquest one foresees as certain are already no longer difficulties.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 640 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- When, therefore, the highly lauded bliss of friendship is subjected to a true estimation, it is found to depend partly on man’s feebleness in enduring suffering, since, in fact, very strong characters are least in need of friendship, partly however in pursuing a common end; in a word, on similarity of interests, whence also the apparently more inseparable friendships are loosened or expire when on one side the dominant interests change, so that they now no longer correspond to those of the other. The pleasures attained through mutually pursued interests can, however, also only be put down to the account of these interests, not directly to that of friendship. The firmest community of interests exists in marriage; the community of goods, of earnings, of sexual intercourse, and of the education of children are strong bonds, which, in alliance with the polar completion of the spiritual qualities of both sexes, certainly suffice to found a strong and lasting friendship, which also perfectly suffices without the aid of love in the narrower sense to explain the beautiful and sublime phenomena of readiness for self-sacrifice in married life. Add to that the powerful force of habit. As the dog maintains the sublimest and most touching friendship and fidelity for his master, to whom not his own choice but chance and custom have bound him, so also the relation of spouses is essentially an alliance of habit; wherefore both mariage des convenance and love-matches after a series of years exhibit on the average the same physiognomy.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 647-648 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- In any case, there is in most marriages so much discord and vexation, that when one looks with unprejudiced eye, and is not deceived by the vain attempts at dissimulation, one hardly finds one in a hundred that is to be envied. This is simply due to the imprudence of men and women, who also do not endeavour in little things to accommodate themselves to mutual weaknesses; to the accidental way in which characters are assorted in marriage; to the equal insistance on rights where indulgence and friendship should compromise; to the convenience of discharging all displeasure, vexation, and ill-humour on the nearest person, who must listen; to the mutual irritability and embitterment which is increased by every fresh case of a supposed infringement of rights; to the sorry consciousness of being chained to one another, the absence of which would prevent a host of inconsideratenesses and disharmonies through fear of consequences.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 648 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- This does not at all contradict the fact that the power of habit at once asserts its right and sets itself in violent opposition when a disturbance or solution of the marriage is threatened from without. In both cases it is always only the painful side of the relation which imposes itself on consciousness. The rending of the worst marriage, which furnished a genuine hell for the partners, always causes so much pain to the survivor, that I have heard an experienced man say, “If a marriage is ever to be broken, then the earlier the better; the more prolonged and closer the ties of habit, the more enduring the pain of separation.” One has only to draw from this perfectly correct judgment the logical consequence, then is separation best before union.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 649 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- When, now, the parties are married, they begin to long for children— another instinct, for the understanding can hardly possess this longing. The instinct goes so far as to urge to the adoption of others’ children, and to the education of them as if they were one’s own. That the latter also is no act of reflection is already evident from the instinct of monkeys, cats, and many other mammals and birds that do exactly the same. Moreover by this procedure an already existing child is merely put into a better situation of life than would else have fallen to its lot.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 649 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- In old age, as we shall see, human beings lose all illusions, save the one illusion of the sole instinct remaining to them, in that they cherish for their children the realisation of their hopes from the same miserable existence, whose vanity they have in all respects perceived in their own case. If they grow old enough to see their children also old people, they certainly lose that too; but then they hope for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Man is never too old to learn.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 651 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- It is in accordance with experience that the individuals of the lower and poorer classes and of ruder nations are happier than those of the elevated and wealthier classes and of civilised nations, not indeed because they are poorer and have to endure more want and privations, but because they are coarser and duller. One need only remember “the shirt of the happy man,” in which story there lies a deep truth. And accordingly I also maintain that the brutes are happier (i.e., less miserable) than man, because the excess of pain which an animal has to bear is less than that which a man has to bear. Only think how comfortably an ox or a pig lives, almost as if it had learned from Aristotle to seek freedom from care and sorrow, instead (like man) of hunting after happiness. How much more painful is the life of the more finely-feeling horse compared with that of the obtuse pig, or with that of the proverbially happy fish in the water, its nervous system being of a grade so far inferior! As the life of a fish is more enviable than that of a horse, so is the life of an oyster than that of a fish, and the life of a plant than that of an oyster, until finally, on descending beneath the threshold of consciousness, we see individual pain entirely disappear. On the other hand, the higher sensibility sufficiently explains why men of genius are so much more unhappy in their lives than ordinary men, to which must be added (at least among reflective geniuses) the penetration of most illusions. This is in accordance with the result of the foregoing examination, which taught us that the individual is so much the better off the more he is entangled in the illusion created by the instinctive impulse (“He that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.”—Ecclesiastes); for, in the first place, it has corrupted his judgment on the true proportion of past pleasure and pain, and in consequence he feels his misery less, and is not so oppressed by this feeling of misery; and, secondly, there remains to him in every direction the happiness of hope, whose partial frustration is quickly followed by new hopes, whether in the same or in another direction. He lives, therefore, always in dreamland, and in all present misery consoles himself with the illusion which promises him a golden future. (Käthchen von Heilbronn or Mr. Micawber in “David Copperfield” will readily occur to the reader.)

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 672-673 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- In the resumé of the first stage of the illusion we saw that peoples in a state of nature are not more wretched, but more happy, than civilised peoples; that the poor, low, and rude classes are happier than the rich, aristocratic, and cultivated; that the stupid are happier than the clever; in general, that a being is the happier the obtuser is its nervous system, because the excess of pain over pleasure is so much less, and the entanglement in the illusion so much greater. But now with the progressive development of humanity grow not only wealth and wants, but also the sensibility of the nervous system and the capacity and education of the mind, consequently also the excess of felt pain over felt pleasure and the destruction of illusion, i.e., the consciousness of the paltriness of life, of the vanity of most enjoyments and endeavours and the feeling of misery; there grows accordingly both misery and also the consciousness of misery, as experience shows, and the often-asserted enhancement of the happiness of the world by the progress of the world rests on an altogether superficial appearance. (This is especially to be laid to heart by those who perhaps are not quite in accord with me, that at the present time the sum of pain in the world outweighs the sum of pleasure.)

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 702-703 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- As the suffering of the world has increased with the development of organisation from the primitive cell to the origin of man, so will it further increase with the progressive development of the human spirit until one day the goal is attained. It was a childish short-sightedness when Rousseau, from the perception of increasing suffering, drew the conclusion: the world must, if possible, turn back—back to the age of childhood. As if the childhood of humanity had not been misery! No; if once backwards, then farther, ever farther, to the creation of the world! But we have no choice. We must forwards, even if we desire it not. It is not, however, the golden age that lies before us, but the iron; and the dreams of the golden age of the future prove still more empty than those of the past. As the burden becomes heavier to the bearer the longer the road on which he carries it, so will also the suffering of mankind and the consciousness of its misery increase and increase until it is insupportable. We may also employ the analogy with the ages of the individual. As the individual at first as child lives for the moment, then as youth revels in transcendent ideals, then as man strives after glory, and subsequently possessions and practical science, until, finally, as old man, perceiving the vanity of all endeavour, he lays to rest his weary head, longing for peace, so, too, Humanity. We see nations arise, mature, and perish; we find also in Humanity the clearest symptoms of growing older. Why should we doubt that, after the energetic activity of manhood, for it, too, one day old age will come, when, consuming the practical and theoretical fruits of the past, it enters upon a period of ripe contemplation, when with melancholy sorrow it overlooks at a single glance all the sufferings so unthinkingly of its past life-career, and comprehends the whole vanity of the previously supposed goals of its endeavour.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 703 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- There is only one difference between it and the individual. Hoary humanity will have no heir to whom it may bequeath its heaped-up wealth, no children and grandchildren, the love of whom might disturb the clearness of its thought. Then will it, imbued with that sublime melancholy which one usually finds in men of genius, or even in highly intellectual old men, hover like a glorified spirit over its own body, as it were, and as (Edipus at Colonos, feel in the anticipated peace of non-existence the sorrows of existence as if they were alien to it, no longer passion, but only a self-compassion. That is the heavenly serenity, the divine repose, that breathes in Spinoza’s Ethics, when the passions are swallowed up in the abyss of reason because they are clearly and distinctly grasped as ideas. But even if we assume that pure passionless state attained, if even the sorrow in self-compassion is glorified, it yet does not cease to be grief, i.e., pain. The illusions are dead, hope is extinct; for what is there still to hope? The dead-tired humanity drags along its frail earthly body wearily from day to day. The highest attainable were indeed painlessness, for where is positive happiness still to be sought? In the vain self-sufficiency of the knowledge that all is vanity, or that in the contest with those vain impulses reason now usually remains victor? Oh, no; such vainest of all vanities, such arrogance of the intellect has long been surmounted! But even painlessness is not attained by hoary humanity, for it is still not pure spirit; it is feeble and frail, and must nevertheless work in order to live, and yet does not know for what it lives; for it has indeed the illusions of life behind it, and hopes and expects nothing more from life. It has, as every very aged and self-knowing man, only one wish more: repose, peace, eternal dreamless sleep that may soothe its weariness. After the three stages of illusion of the hope of a positive happiness it has finally seen the folly of its endeavour: it finally foregoes all positive happiness, and longs only for absolute painlessness, for nothingness, Nirvana. But not, as before, this or that man, but mankind longs for nothingness, for annihilation. This is the only conceivable end of the third and last stage of the illusion.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 703-704 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- We began this chapter with the question whether the being or the not-being of the present world deserves the preference, and have been obliged to answer this question, after conscientious consideration, thus, that all secular existence brings with it more pain than pleasure. As cause of this disproportion we have seen those moments collected under (1.) in the first stage of the illusion, which bring it about that all volition must necessarily be attended by more pain than pleasure, that thus all volition is foolish and irrational. Even then the only possible result was clearly to be perceived; the whole subsequent inquiry was merely the empirical inductive proof of the correctness of that consequence, which we certainly could not omit if we were to proceed surely.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 704-705 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- If this result appears to the reader who has had the patience to accompany me so far a cheerless one, I must assure him that he was in error if he sought to find consolation and hope in philosophy. For such ends there are books of religion and edification. Philosophy, however, has but a single eye for truth, unconcerned whether what it finds suits the emotional judgment entangled in the illusion of instinct or not. Philosophy is hard, cold, and insensitive as a stone; floating in the ether of pure thought, it endeavours after the icy cognition of what is, its causes, and its essences. If the strength of man is unequal to the task of enduring the results of thought, and the heart, convulsed with woe, stiffens with horror, breaks into despair, or softly dissolves into world-pain, and for any of these reasons the practical pyschological machinery gets out of gear through such knowledge,—then philosophy registers these facts as valuable pyschological material for its investigations. It likewise registers it when the result of these considerations in the sympathising soul of the more strongly built natures is a righteous indignation, a manly wrath clenching the teeth, a fervid fury at the frenzied carnival of existence, or when this rage turns into a Mephistophelean gallows-humour, that with half-suppressed pity and half-unrestrained mockery looks down with a like sovereign irony both on those caught in the illusion of happiness and on those dissolved in tearful woe,—or when the heart wrestling with fate spies after a last way of deliverance from this hell. To philosophy itself, however, the unspeakable wretchedness of existence— as manifestation of the folly of volition—is only a TRANSITION-MOMENT of the theoretical development of its system.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 705 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- We have seen that in the existing world everything is arranged in the wisest and best manner, and that it may be looked upon as the best of all possible worlds, but that nevertheless it is thoroughly wretched, and worse than none at all.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 710 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- According to our view, with suppression of the individual will at least all the organic functions dependent on the unconscious will, as heart-throb, respiration, &c., must instantly cease, and the body collapse as corpse. That this too is empirically impossible will be doubted by nobody; but whoever is obliged to first kill his body by refusal of food proves by that very act he is not able to deny and abolish his unconscious will to live. But supposing the impossible to be possible, what would be the consequence? One of the many rays or individual objectifications of the One Will, that which related to this individual, would be withdrawn from its actuality, and this man be dead. That is, however, no more and no less than happens at every decease, no matter to what cause it is due, and to the Only Will the consequences would have been the same if a tile had killed that man; it continues after, as before, with unenfeebled energy, with undiminished avidity, to lay hold of life wherever it finds it and can lay hold of it; for to acquire experience and become wiser by experience is impossible to it, and it cannot suffer a quantitative abatement of its essence or its substance through the withdrawal of a merely one-sided direction of action. Therefore the endeavour after individual negation of the will is just as foolish and useless, nay, still more foolish, than suicide, because it only attains the same end more slowly and painfully: abolition of this appearance without altering the essence, which for every abolished individual phenomenon is ceaselessly objectified in new individuals. Accordingly all asceticism and all endeavour after individual negation of will is perceived and proved to be aberration, although an aberration only in procedure, not in aim. And because the goal which it endeavours to gain is a right one, it has when rare, by ever whispering in the world’s ear a memento mori, as it were, and provoking a presentiment of the issue of all endeavour, a high value; it becomes, however, injurious and pernicious when, attacking whole nations, it threatens to bring the world-process to stagnation, and to perpetuate the misery of existence. What would it avail, e.g., if all mankind should die out gradually by sexual continence? The world as such would still continue to exist, and would find itself substantially in the same position as immediately before the origin of the first man; nay, the Unconscious would even be compelled to employ the next opportunity to fashion a new man or a similar type, and the whole misery would begin over again.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 712-713 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- For him, who has grasped the idea of development, it cannot be doubtful that the end of the contest between consciousness and the will, between the logical and the non-logical, can only lie at the goal of evolution, at the issue of the world-process; for him who before all holds fast to the universality and unity of the Unconscious, the redemption, the turning back of willing into non-willing, is also only to be conceived as act of each and all, not as individual, but only as cosmic-universal negation of will, as the act that forms the end of the process, as the last moment, after which there shall be no more volition, activity, or time (Rev. x. 6). That the cosmic process cannot be thought without an end in time, cannot be of endless duration, is presupposed; for if the goal lay at an infinite distance, a finite duration of the process, however long, would bring no nearer the goal, that would still remain infinitely remote. The process would thus no longer be a means for reaching the goal, consequently it would be purposeless and aimless. As little as it would comport with the notion of development to ascribe an infinite duration in the past to the world-process, because then every conceivable development must be already traversed, which yet is not the case, just as little can we allow to the process an endless duration for the future; both would abolish the idea of development towards a goal, and would put the world- process on a level with the pouring of water into a sieve of the daughters of Danaus. The complete victory of the logical over the alogical must therefore coincide with the temporal end of the world-process, the last day.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), pp. 714-715 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6

- Whether humanity will be capable of so high an enhancement of consciousness, or whether a higher race of animals will arise on earth, which, continuing the work of humanity, will attain the goal, or whether our earth altogether is only an abortive attempt to reach such goal, and it will only be reached, when our little planet has long been reckoned to the frozen celestial bodies, on a planet invisible to us of another fixed star under more favourable conditions, is hard to say. Thus much is certain, wherever the process may come to an end, the goal of the process and the contending elements will always be the same in this world. If really humanity is able and called to bring the world-process to a final issue, it will at all events have to do this at the height of its development under the most favourable circumstances of the earth’s habitableness, and therefore we do not need for this case to trouble about the scientific perspective of a future congelation and refrigeration of the earth, since then long before the occurrence of such a terrestrial refrigeration the world-process altogether would have been arrested, and the existence of this kosmos with all its world-lenses and nebulæ have been abolished.

- trans. William Chatterton Coupland, Routledge (2010), p. 715 ISBN 978-0-415-61386-6