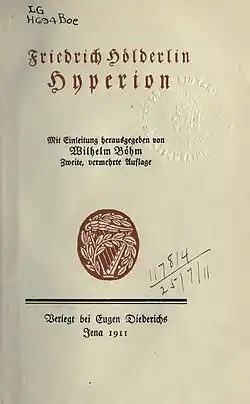

Friedrich Hölderlin

.jpg)

Johann Christian Friedrich Hölderlin (20 March 1770 – 6 June 1843) was a major German lyric poet, whose work bridges the Classical and Romantic schools.

Quotes

- Wir sind nichts; was wir suchen, ist alles. - Fragment von Hyperion, aus: Neue Thalia, Vierter Band, Hrsg. Friedrich Schiller, Georg Joachim Göschen, Leipzig 1793, S. 220

- We are nothing; what we search for is everything.

- Wo aber Gefahr ist, wächst // das Rettende auch. - Patmos, 1803, Vers 3f. in: Gedichte von Friedrich Hölderlin, Druck und Verlag von Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1873, S. 133

- Wherein lies the danger, grows also the saving power.

- Being at one is god-like and good, but human, too human, the mania

Which insists there is only the One, one country, one truth, and one way.- "The Root of All Evil" as translated by Michael Hamburger

- You seek life, and a godly fire

Gushes and gleams for you out of the earth,

As, with shuddering long, you

Hurl yourself down to the flames of the Etna.So by a queen's wanton whim

Pearls were dissolved in wine- heed her not!

What folly, poet, to cast your riches

Into that bright and bubbling cup!Yet still are you holy to me, as the might of the earth

That bore you away, audaciously perishing!

And I would follow the hero into the depths

Did love not hold me.- "Empedokles"

- The earth with yellow pears

And overgrown with roses wild

Upon the pond is bent,

And swans divine,

With kisses drunk

You drop your heads

In the sublimely sobering water.

But where, with winter come, am I

To find, alas, the floweres, and where

The sunshine

And the shadow of the world?

Cold the walls stand

And the wordless, in the wind

The weathercocks are rattling.- "Halves of Life"

- Wer das Tiefste gedacht, liebt das Lebendigste.

- He who has thought most deeply loves what is most alive.

- “Sokrates und Alcibiades”

- He who has thought most deeply loves what is most alive.

Hyperion

- Immerhin hat das den Staat zur Hölle gemacht, daß ihn der Mensch zu seinem Himmel machen wollte.

- What has always made the state a hell on earth has been precisely that man has tried to make it heaven.

- As translated by Michael Hamburger

- Now we were standing close to the summit's rim, gazing out into the endless East.

- What is all that men have done and thought over thousands of years, compared with one moment of love. But in all Nature, too, it is what is nearest to perfection, what is most divinely beautiful! There all stairs lead from the threshold of life. From there we come, to there we go.

- What is the wisdom of a book compared with the wisdom of an angel?

- I call on Fate to give me back my soul.

- It was not delight, not wonder that arose among us, it was the peace of heaven.

A thousand times have I said it to her and to myself: the most beautiful is also the most sacred. And such was everything in her. Like her singing, even so was her life.

- Before either of us knew it, we belonged to each other.

Quotes about Friedrich Hölderlin

- When you read Hölderlin, you see feints and variations that put him with Celan; it was reading Hölderlin that gave Rilke the impetus for his Duino Elegies (his "Gods" are like Rilke's "Angels", tutelary presences that don't quite convince us that they exist: "Celebrate – yes, but what?" Hölderlin writes somewhere, but it sounds eerily like Rilke). Sometimes reading him can feel as bitterly sacramental as Trakl, the great Austrian poet who took his life following the battle of Grodek in the first world war. All that doesn't really "translate". If you really want to read Hölderlin – or any one of the other great "national" poets – you should learn German (or Russian or French or Spanish).

- Michael Hofmann, 'The unquenchable spirit', The Guardian (20 November 2004)

- Friedrich Hölderlin saw his times – like Wordsworth, Beethoven and Hegel, he was born in 1770 – as in fermentation, as a messy process that may lead to clarity. Most of his poems are concerned with the nature and possibility of transition. Through the complexity of their syntax, the intricate jointing of their rhythms, and their abrupt shifts between images, we are trained in the dynamics of moving through uncertainty, and given experiences of how it can resolve itself into coherence. But almost at once comes the correction, the recognition that reality does not yet match the hopes that it is nevertheless capable of nourishing. If we are taken back to ancient Greece, the chief sustainer of Hölderlin's belief that a better world was possible, to witness, as in his poem “The Archipelago”, a vision of the growth of Athens so powerful it seems to be happening before our eyes, it is only to have the illusion wrecked by the reminder that Athens now lies in ruins. “The Archipelago” ends with the sober desire to understand the “changing and becoming” (“das Wechseln / Und das Werden”) it has so successfully embodied in its lines, so at a kind of remove; and most of Hölderlin's completed poems end quietly.

- Charlie Louth, 'Urge for the impossible', Times Literary Supplement (13 November 2020)

- It was the function of poetry, not of himself as the poet, that he thought highly. That function was sacred, for the poet was the priest of the divine. Mr. Peacock – we think rightly – compares him with Blake both for his isolation among his contemporaries and for the purity of his utterance, which seems to carry with it so little base or neutral matter. He can be compared with Blake also for his sense of inspiration; but whereas the divine for Blake was gradually concentrated in a power which he identified with the god of Christianity, Hölderlin sought for it in the gods. These gods of his – of whose imaginative reality his poetry convinces us – appear to have been created by a singular combination of German philosophical pantheism and a profound insight into the religious sources of Greek poetry.

- John Middleton Murry, 'Hölderlin', Times Literary Supplement (31 December 1938), quoted in John Middleton Murry, Poets, Critics, Mystics: A Selection of Criticisms Written Between 1919 and 1955, ed. Richard Rees (1970), p. 20

- A review of Hölderlin by Ronald Peacock

- The fact remains that Hölderlin's creed was a kind of pantheism – thought it has many varieties – and that his supreme value was beauty – though beauty is variously understood and experienced. Beauty for Hölderlin was not a thing in itself, but rather the grace attendant on a harmonious manifestation of the powers of Nature. Athenian civilization was the type of the beautiful, because Nature achieved in it her own perfect form.

- John Middleton Murry, 'Hölderlin', Times Literary Supplement (31 December 1938), quoted in John Middleton Murry, Poets, Critics, Mystics: A Selection of Criticisms Written Between 1919 and 1955, ed. Richard Rees (1970), p. 21

- The one poet who both grew out of but gave form to many of the thoughts and philosophies of these groups was Friedrich Hölderlin and though his disillusionment with the French revolution was great, the poems he wrote in response to it seek to bring a the sense of revolutionary elan and hope which it promised into his oeuvre. He did this by returning to the classical tradition and a reworking of ancient Greece which, instead of the usual promotion of a static understanding of the way history works, he emphasised the old Heraclitean adage that everything is in flux. Hope sprung eternal because hope emerged out of changed circumstances and out of the fundamental human desire to make things better, no matter how that desire may become diverted and deformed by the contingencies of the every day. His rediscovery of Dionysian desire is clear in his work.

- Peter Thompson, 'Friedrich Hölderlin', The Guardian (1 May 2010)

- History has a way of reducing individuals to flat, two-dimensional portraits. it is the enemy of subjectivity, which is why Stephen Dedalus called it "a nightmare from which I am trying to awake". If we think of Kierkegaard, of Nietzsche, of Hölderlin, we see them standing alone, outside of history. They are spotlighted by their intensity, and the background is all darkness. They intersect history, but are not a part of it. There is something anti-history about such men; they are not subject to time, accident and death, but their intensity is a protest against it. I have elsewhere called such men "Outsiders" because they attempt to stand outside history. which defines humanity on terms of limitation, not of possibility.

- Colin Wilson, Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs (1964), pp. 13-14