Because backward compatibility.

“Alt codes” are older than Windows. They started out on the IBM PC in 1980 (or maybe a little later, I don't know if the feature was present in the original PC). That computer had a character encoding with 256 code points (single-byte encoding). Most programs used a text mode display, capable of displaying in a single, fixed-width, 256-character font supplied by the graphics card called a code page. The default code page on the PC was CP437, which included ASCII as well as diacritics and punctuation characters for mostly Western European languages, a few mathematical and technical symbols, and line drawing characters. The firmware provided with the computer (BIOS) translated presses of Alt+numpad digits into the corresponding character, to allow people to input characters that were not present on the keyboard. For example, Alt+(NumPad1 NumPad6 NumPad5) inserted character 165, which in CP437 is Ñ.

Later Windows came along. With a graphical environment, line drawing characters were not useful, and you could switch between multiple fonts in the same document. So Windows had different character sets (often known as “ANSI code pages” although they didn't actually follow ANSI standards) which omitted those characters to make room for more characters commonly used in text. These were still (except in Asian editions of Windows) single-byte character sets, originally ISO 8859 (e.g. ISO 8859-1 a.k.a. Latin-1 for Western European languages), later extended to “Windows code pages” such as Windows-1252. Windows extended Alt codes to support the Windows code pages while remaining compatible with the habits of users who had learned the “DOS” (really BIOS) code points. So for example, assuming default settings with CP437 as the DOS code page and 8859-1 or Windows-1252 as the Windows code page, Alt+(NumPad1 NumPad6 NumPad5) would still insert ñ from CP437, but if you typed a 0 before the number, you'd get the number from the Windows code page: Alt+(NumPad0 NumPad1 NumPad6 NumPad5) for ¥, Alt+(NumPad0 NumPad2 NumPad0 NumPad9) for Ñ.

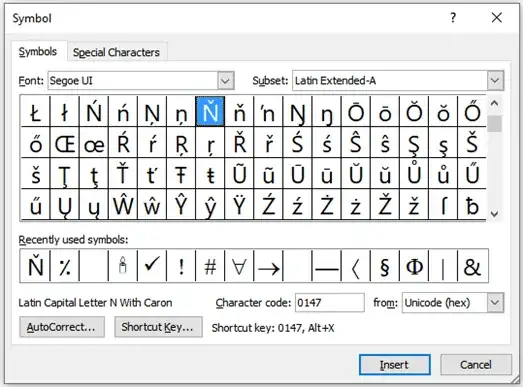

And later, Unicode came along, with thousands of code points rather than 256. And still Windows didn't want to break users' habits, so they kept Alt+numpad digits using a BIOS code point if the sequence of digits is a number between 1 and 255 without a leading 0, and using a Windows code point if the sequence of digits is a number between 32 and 255 with a leading 0 (IIRC control characters in the range 0-31 can't be typed that way). This explains why Alt+(NumPad0 NumPad1 NumPad4 NumPad7) inserts “: it's code points 147 from Windows-1252. Both Windows-1252 and Unicode extend ISO 8859-1, which only defines glyphs for characters in the ranges 32–126 (ASCII) and 160–255. This explains why alt codes with a leading 0 in these ranges match with Unicode, but not for 127-159, where ISO 8859 and Unicode have control characters but Windows code pages added visible glyphs.

When designing alt codes for Unicode characters, the designers of Windows had to pick a mechanism that didn't conflict with the two established mechanisms. Also, Unicode charts use hexadecimal codes, so they couldn't rely on the number pad alone. Alt+(A A A A) means the shortcut Alt+A four times, so there had to be a different way of inserting ꪪ. They picked Alt+(NumPad+ hex digits), where the hex digits can be typed on the main keyboard area.

(Note: I'm not sure if everything in this answer applies to all modern versions of Windows or if some variations or configurations apply. My Windows knowledge is very out of date.)